5 Questions with Creative Exchange: What we have learned from our artists

Since August 2016, Creative Exchange has been asking each of our Artists With Impact a series of five questions, which appear at the end of every profile. We did this to create a thread of continuity from one profile to the next: whether we’re interviewing the head of a multi-million-dollar arts organization in a major city or a solo artist from the Alaskan Bush, we want our readers – which include a whole lot of other artists – to see these five questions as creating a common reference point between artists of wildly varying backgrounds, experiences, and exposure. These five questions reflect issues common to all artists, regardless of how much experience they have or funding they receive – and yes, one of the questions is about funding, an issue near and dear to every artist’s heart.

As we have reviewed almost 18 months’ worth of profiles, we have seen a lot of similarities in how our artists chose to answer these questions, and a few noteworthy differences. We hope that, if nothing else, you take away from this a clearer understanding that all of the questions and concerns you grapple with as an artist, or simply as a human being, are common to everyone. We all want the same things, need the same things, worry about the same things, and obsess over the same things.

With that in mind, take a look at some of the highlights from “Creative Exchange: Five Questions.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

The majority of the artists we talk to tend to work collaboratively, and most of them enjoy it (for the most part). Documentary filmmaker Jonathan David Kane says he “only” likes to collaborate. Designer Cézanne Charles says, simply, “Often. A lot.” “ARTivist” Rosalia Torres-Weiner says she loves collaborating: “I always learn something new.”

Artists primarily expressed interest in collaborations in which everyone involved brings their own fresh ideas, unique perspectives, and individual talents to the table, with each carrying their own weight and fully taking on their share of responsibilities. Artists also enjoy collaborations most when they feel they’ve learned something new from those they worked with, were able to unite with others towards common goals, and were exposed to diverse groups and different viewpoints in a constructive way.

Revolutionary artist Dread Scott most enjoys the collaborations “when the work that is created couldn’t happen without all partners contributing.” Integrative community artist Tia Richardson says, “I like collaborating with people who don’t consider themselves artists who want to come together to share something that’s important to them, even though they might not know what the end result will look like or how they might be involved in the process.”

But not every artist loves collaboration; for many people, much of the creative process is internal, and sometimes working with others isn’t always an enjoyable experience. Muralist Chip Thomas, aka Jetsonorama, works on large-scale international collaborative projects but admits that collaboration can be “challenging.” Claire Nelson, founder of the Urban Consulate, says she likes to partner on everything – “Nothing solo!” – but also finds she works best in small groups of two or three: “I get overwhelmed with larger collaborations, trying to get everyone on the same page.” And photographer Tom Keifer admits, quite simply, “I’m not that collaborative kind of guy.”

(2) How do you a start a project?

This probably goes without saying, but most projects tend to start with an idea. Some artists like to write their ideas down while others like to talk them out, but nearly all said they find inspiration in the world around them, and often start their projects based on a need they see within their communities.

Artist collective t. Rutt starts when they are “inspired or unispired by the state of the world around us.” George Marks, painter and driving force behind the Arnaudville Experiment, explains that “it’s really about identifying some kind of problem or issue or something that needs to be righted in some way; something that’s impactful for the entire community.” Community organizer Kathy Mouacheupao say she usually starts projects with “wanting something really awesome to happen in my community.”

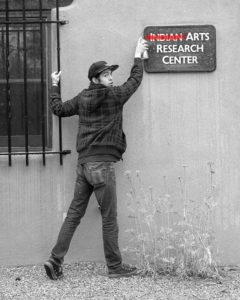

Photographer M. Jenea Sánchez explains, “I usually start a project when I discover something is missing from the visual fabric of our culture, or when something is misrepresented in the dominant narrative.” She also does a lot of research in order to gain a historical foundation at the outset of each new project, something Dread Scott also says he spends a lot of time doing.

Artists often talk about an idea starting as a feeling that nags at them until they do something with it. Some, like service provider social practice artist Ori Alon, call it “intuitive;” others, like Tom Keifer, feel their ideas are “obvious” to them. Visual artist Spencer Merolla says, “There’s usually some kind of mad scientist aspect about it. I get an idea and then just become totally consumed by it and basically disappear for a while.” Claire Nelson agrees: “I’m all gut. I see a gap, I want to fill it. I get obsessed with an idea — wake up thinking about it, fall asleep thinking about it, do a ton of research and development.”

Artists have different methods of working on ideas. Poet Yolanda Wisher starts with “mind maps and doodles.” Artist-entrepreneur Warren Montoya has an idea book that he carries around. “I recommend to anyone who has a lot of ideas, especially random ideas, to get one! This is where many of my projects have begun,” he says. Sculptor Ian Trask recommends “cleaning up and reorganizing a messy space.” Lucas Koski starts by talking out loud while walking his dog.

And while all projects begin with an idea, some artists begin at the end. “I think about what the ending should be,” musician Kelly Jolly says of her process of starting a new project. As a public art organizer, Brooke Foy says, “A project has not begun until I have a budget.” Traditional Inuit tattoo artist Holly Mititquq Nordlum advises, “Dream big; start small.”

(3) How do you talk about your value?

This question consistently gave our artists’ pause. Many of them struggled to answer it, and said that it something they have a hard time defining or articulating. Theatre-maker Ifrah Mansour pretty much speaks for every artist when she laughs, “Being asked to talk about my value is the most painful experience!”

Holly Mititquq Nordlum says she simply doesn’t talk about it, then adds, “I still have a hard time charging for things but try to always be fair.” Kelle Jolly feels like she always has to prove herself. Some see their value in their experience, knowledge, and work ethic, while others talk about the difficulties of self-evaluating and self-advocating and how uncomfortable, but necessary, it can be to do those things.

Many artists align their value with their communities. Dread Scott and t.Rutt both talk about the importance of ideas that are transformative to society and shifting the status quo, making sure voices that are outside of the dominant culture are heard. M. Jenae Sanchez says her value is rooted in the continuum of the historical fight of her indigenous heritage and her place as a female surrounded by a history of patriarchy. “I value that fight, therefore I value myself and continue the fight,” she says.

Community activist Jaclyn Roessel of Grownup Navajo recognizes that, as a young Native woman, “I know there is a need for people like me to have this opportunity.” Rosalia Torres-Weiner says her value lies in empowering the Latino community to tell their own stories for the dominant culture to hear them. Brooke Foy says the most important aspect of her projects is the value they bring to the community, while designer Leon Wang states that his value is for the community to decide. “It’s not for me to answer how much value I’m providing.”

For some artists, it is important to them that their works demonstrate the value of artists and art to society. Ayumie Horie, co-founder of the Democratic Cup, says, “What we contribute to political discourse as artists is rich in emotional value because in the end, political values are spiritual values.” As an artist and activist, Beth Grossman says, she helps communities understand that the arts and artists can play a central role in every initiative. And painter Ryan Romer explains, “‘Human value’ is some of the verbiage I like to use when describing myself or other artists. It’s the human value. We need to put the artist back as a person of value in our culture, in any culture.”

Ultimately, it is a difficult, if not outright impossible, task to assign a dollar amount to the work that many artists do – this is certainly the case with social practice artists, but is also true of really any artist working in any medium for any size audience. George Marks states, “The value of something is not so much that monetary piece as it is realizing that the end result, the thing that happens at the very end, the people stepping forward and taking ownership and beginning to lead projects and making connections – you can’t put a monetary value on that because that’s what makes it sustainable.”

(4) How do you define success?

“Success” is a nebulous term, relative to each individual defining it. If you asked 10 people what they consider to be “success,” you would probably get 20 answers. Each of our artists has their own unique view of what it means to be successful, or what makes them say at the end of a project or event, “THAT was a success.”

Some artists expressed that they never quite feel “successful,” or that the concept is something they are still trying to define for themselves. Others feel a sense of success when people tell them that they’re still thinking about what they saw or experienced, or that the piece of public art they pass every day brings them joy. Mona Magno, founder of Free Music for Free People, says, “If we inspire one person…then we have definitely succeeded!”

One thing many of the artists repeated is that their measure of success is in direct relation to their impact within the community, and that they feel they have been successful when their project or idea becomes bigger than themselves.

Ori Alon states, “If my work is helpful to others and they find some compassion or social acceptance, that’s my definition of success.” Ayumie Horie says, “If, through this project, we help someone clarify their values, bolster their voice as an important part of democracy, or help foster one connection between people, then the Democratic Cup is a success.” And Cézanne Charles says success is “when the project is received – when it’s no longer ours, when people get to myth-make and story-tell about the project.”

George Marks echoes this thought, defining success for himself as the moment when he no longer has to be involved in the process, when people who might not have ever even thought of themselves as artists or leaders in any way start to feel comfortable enough to speak up with their own ideas and begin taking ownership over the things they’re all trying to create together.

Speaking more broadly, Dread Scott states, “In the grandest way, there needs to be a revolution and my work needs to be contributing to that.” And Leon Wang feels a project has been successful “if we are able to make an impact within our community, and also extend outside the movement with clear and unifying message.”

Other artists feel the mere act of conversation and idea-sharing is a success. Social activist Fran Illich says, “For me it’s all about finding those two or three people with whom a conversation can happen.” Claire Nelson defines it as “creating a new awareness that didn’t exist before.” Cultural organizer Tana Hargest says that the greatest success is when everyone involved realizes that they created something new together.

M. Jenea Sánchez says success is something that others feel: “Success should not be measured in numerical values but by one’s ability to awaken humans’ emotions.” Tia Richardson agrees, stating, “If something resonated with them about the process that made them see things in a different way or made them open up a little, if I hear them self identify that, that’s successful.”

For Steven Renderos, Organizing Director of the Center for Media Justice, success is when a story they have told helps to change the material conditions people are struggling under, such as when his organization led a campaign to lower the prohibitive costs of making calls from prison and he hears back from people thanking him. Haley Honeman, a teaching artist whose theatre work addresses the stigma around suicide, says, “Usually I think success means that the process has felt important and enjoyable even if there have been difficult moments, especially in the kind of work I do. I think it’s going to be uncomfortable at times but that’s okay.”

For some artists, success is more of a personal experience. Poet Ursula Rucker states, “There are so many ways to be successful, from the smallest to the greatest. When I accomplish anything I’ve set out to accomplish, I’m successful.”

“I feel like whatever I’m doing, as long as I’m a little bit more awake than the day before, then the day was a success,” says Ehren Kee Natay, musician and craftsman. Emmett Phillips, hip hop artist and teacher, considers something a success “if I can look at a project or anything I’ve invested energy in and feel a sense of honor about it and feel like my integrity was intact throughout it.”

But for Spencer Merolla, the word itself is problematic. “The word ‘success’ always rings a little hollow to me. It’s too binary and outward-facing. It sounds as if you are ticking things off to prove something, whether to yourself or someone else. Growth is more interesting to me.”

(5) How is your work funded?

No matter how “successful,” financially or otherwise, an artist might be – no matter how small or large their audience, how much media coverage they’ve received, or the size of their social networks – funding is an issue that affects ALL artists, and everyone has something to say about it.

Some artists are fortunate enough to receive support from foundations and other organizations in the form of grants and fellowships. Of those that do, an even smaller number are actually able to fully support themselves through such funding.

The lucky few, as it would seem, since most of the people we spoke with also have some other source of income. Some, who might not have received grants themselves, have been able to partner with other organizations that have money for specific projects and hire them on as contractors. Others have long-term relationships with other organizations, working as de facto employees. Some rely on a hodgepodge of paid gigs, others on donations. Some of the more formalized organizations are able to charge membership dues. Another lucky few artists have very supportive partners or family members that enable them to pursue their creative practices.

Those that make tangible works that can be sold subsist on sales and commissions. Some have even been able to take a more entrepreneurial approach to their work: Blayze Buseth, a ceramicist who specializes in hand-carved effigies, has opened his own business creating custom-made memorial urns, while Warren Montoya has made his art his business into a business that also supports other artists.

Montoya also relies on some forms of crowd-funding, a strategy that has become increasingly popular. Event organizer Dylan Yellowlees looks towards crowd-funding because, she says, the public then feels a stronger sense of investment in a project, though she also relies on grants and in-kind sponsorships. Ian Trask’s best method is to spend as little on the production of the work in the first place (perhaps a little easier for him than most, as he works primarily with waste materials), but will also fall back on crowd-funding and crowd-sourcing when a project calls for it. “When it needs be done, there’s Kickstarter to lean into my network and ask for help. Sometimes as an artist you need to ask for help,” he says.

Many describe their work as being “self-funded,” which means they have full- or part-time jobs that may or may not be related to their practices and they use some of that earned income to pursue their creative endeavors. Many, like Emmett Phillips and Haley Honeman, find that working as a teaching artist affords them the time, stability, and mental space to do what they love for a living as well as outside of work. Dread Scott has the most unique way of describing it: “I take money otherwise obtained through nefarious things and put it to good use.”

On the opposite side of self-funding are those whose full-time jobs do not support their art. Cézanne Charles says she and her partner John Marshall try to keep their jobs as separate as possible from their practices, for which they have received foundation support and commissions. “As much as possible we try to use our day jobs to fund our lives and not our work,” she explains. “We really try not to have it pay for the production or research of the artwork. We’re not at the point of earning salaries through our projects.”

Most ultimately rely on some combination of grants, gigs, commissions, sales, donations, and unrelated full- or part-time work. As Tana Hargest astutely states, “I have learned over the years to not be reliant on one source of revenue.” Fran Illich takes a guerilla artist approach when he says, “By any means necessary.” Ursula Rucker just laughs, “By the grace of God.” Lucas Koski sums it all up in one word: “Hustle.”

Still, of those who receive support from foundations, there is a bit of reluctance on relying too much on grant money, or being a part of what has been referred to as the “nonprofit industrial complex.”

Ifrah Mansour has some conflicted feelings on this, which are worth repeating at length:

“I’m afraid of losing my creativity now that I have grants. I hope I never lose my ability to stretch a dollar. There’s something very organic that happens when something doesn’t exude money. I work in a neighborhood where people can’t find jobs; they don’t have a lot of money; they live in low income housing with no access to a library or a grocery store. It’s been very important to me to not plot something that exudes money or privilege.

‘It feels good to have grants, but at the same time you have to be mindful of the people you want to impact the most. With the last project I made sure to use community members to build a house because this project has to address the social issue of able-bodied people or elders not being able to find jobs. There are a lot of social elements that go into this money thing. I feel like I’m losing my creative self every time I apply for a grant. Thinking about it in this money-driven way I feel like it’s very soul-wrenching and that’s really a horrible place to put an artist. I also I hope I don’t lose my creativity. When I was poor and had nothing I was able to create these rich works because money wasn’t a question anyway. That would be the ultimate death of my soul, saying I can’t make something because of money.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………..

In all, our artists almost universally have one thing in common, regardless of the scope of their reach or how their work gets funded: they are all artists whose work is community-minded, whether done in direct collaboration with community members or designed with the intention of reflecting, uplifting, and engaging their communities. What sets Creative Exchange artists apart is not a particular style, but an ethos: one that situates themselves as individuals as parts of a larger whole, whose creative contributions have value and impact within the greater community in which they exist.