Ori Alon spreads positivity through paperwork

Ori Alon’s inspiration for the Center for Supportive Bureaucracy began ten years ago when he was an art student in West Jerusalem. He started a performance project by sitting in outdoor markets with a typewriter and some stamps and envelopes and offering letter-writing services to others. People would approach him to write a letter to themselves or someone else, then he would compose and type two copies of the letter on his typewriter (keeping one for his own archives).

“Some letters were very emotional, some were funny, almost all were very therapeutic, and some were very vulnerable,” he says. Each person was giving him something of themselves, and in return he was giving them his time, attention, and ability to listen. Much of the therapeutic element was in exactly that, he says: “It was all just me listening. I was interviewing people, helping them to phrase what they wanted to say about themselves.”

This was how Alon started on the concept of being a service provider social practice artist, sketching his understanding of “service” as an art form, in which the product he was producing was something written rather than creating a visual piece and showing it to people “hoping they like it.”

This performance art project he used in art school as a tool to help people formed his basic understanding of social practice art, a kind of creative practice that, at this time in 2006, was just starting to take shape as its own distinct creative practice with a name of its own.

Alon recalls that around this same time a couple of students who had found a box of blank report cards approached him in one of the markets he was at and asked if he had ever had a bad year at school. He recounted a particularly troubling disciplinary experience from the first grade that had stuck with him all this time, and they issued him a “refurbished report card” citing all “A”s.

“It was a bit of joke but it was really meaningful for me,” he remembers. “Using that humor was a very healing experience. There was something very powerful in this approach, even more than therapy. I kept thinking about it, then I had kids and moved to the United States a few years later, and I started issuing certificates of recognition to people.”

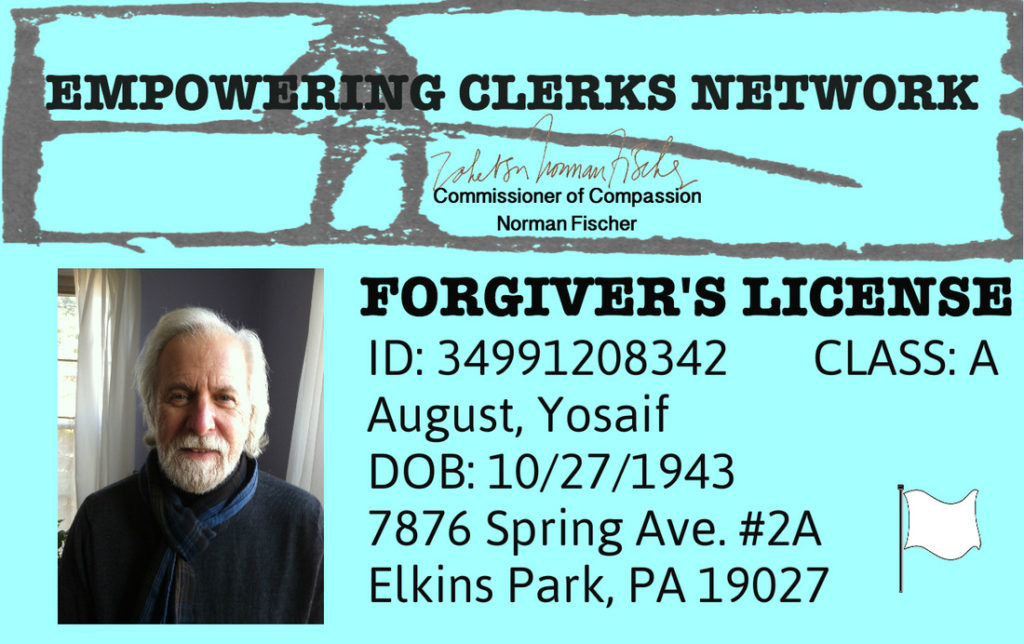

After moving to Brooklyn with his family, Alon started the Center for Supportive Bureaucracy, through which he produces licenses, permits, and certificates, and began training other “Empowering Clerks.” There are now over 40 clerks in the Empowering Clerks Network, all trained to produce a number of custom-made documents designed to spread a little bit of joy.

These documents include professional-looking paperwork like a Forgiver’s License (Class A&B); Joy Permits (6 and 12 months); Refurbished Report Cards; Adults Special Achievement Stickers; a Certified Apology Declaration (447-D); Open Carry permits for musical instruments; the OK Parent Award; the Village Fool Diploma; and a Racism Release Form.

Alon jokes that many of these printed and “authorized” certificates are actually of higher production quality than university diplomas people spend tens of thousands of dollars to earn, and also democratizes the culture of awards – allowing everyday people, and not just champion sports stars and the like, to receive “official” recognition for positive acts.

“There is something very satirical about the project, but it is also very serious and very sincere,” he explains. “I would say on a basic level it’s a very positive message, but there is also a political message of traditional clowning and subverting authority. Issuing a document that looks better than a university diploma – there’s something funny about it. And if someone can get an award for friendship, why do we value this less than things like sports and other things people typically receive awards for?”

And by using a medium as banal as official-looking paperwork and documents, Alon says, “There is a window we can use for creating compassion through this bureaucratic work.”

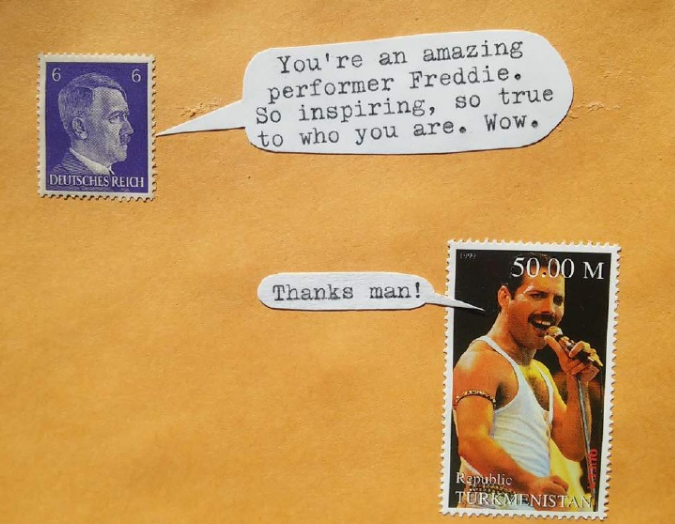

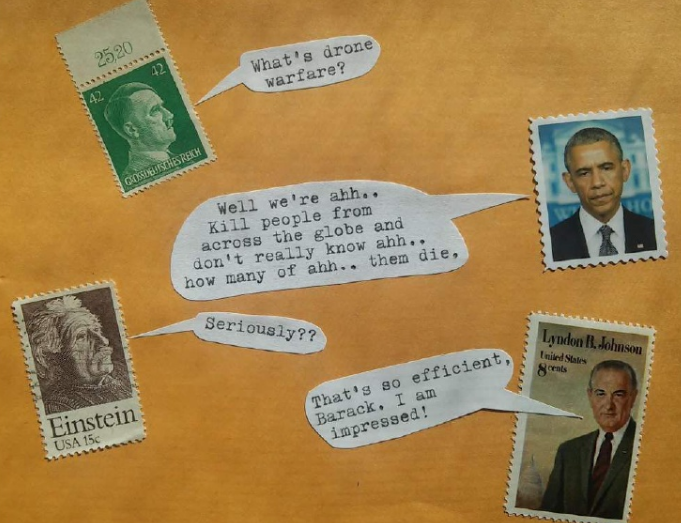

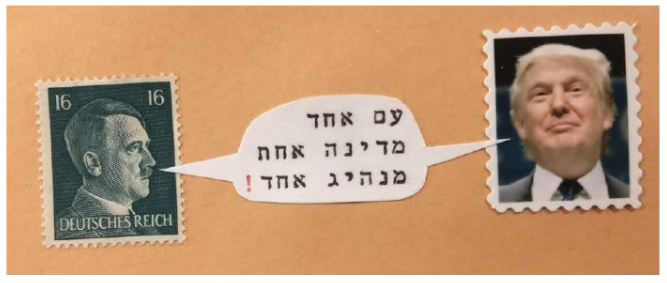

Alon also runs a community publishing house called Alfassi Books, and creates political comics using vintage postage stamps. In these comics, Hitler and Stalin have long dialogues about the nature of happiness, and Hitler praises Freddie Mercury for being true to himself.

“These comics are bringing out an existential truth and doing it in a very simple form,” Alon says. “With Hitler and Stalin talking about happiness, I think most violence in the world comes from unhappiness. Something clicks with this piece – we already know that dictators and criminals are unhappy.”

He says a lot of his comics are more obviously political than the documents produced by the Center, which tries to be nonpartisan.

“I don’t have messages,” Alon says. “I went to many political events in the last year, but I don’t present myself as a political artist, so the comics would be the more political works. A lot of the pieces are very harsh in that aspect.”

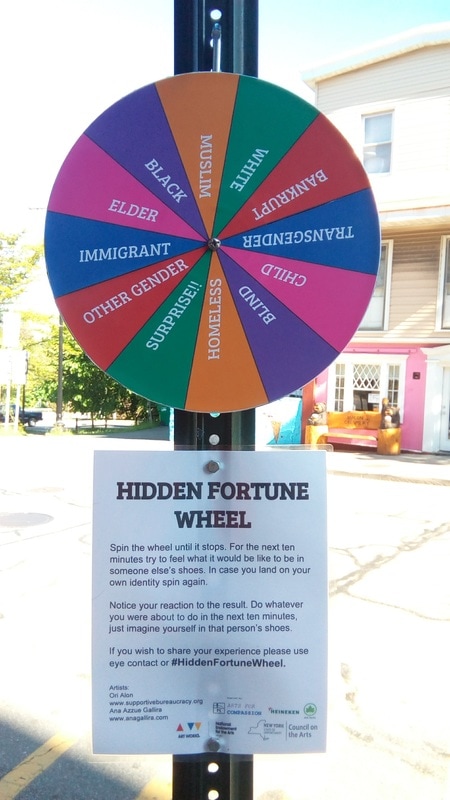

Alon also creates pieces of public art, such as the Hidden Fortune Wheel, a project created in collaboration with artist Ana Azzue Gallira. The Hidden Fortune Wheel can be recreated by anyone – there are instructions online on how to create one, including a template – and asks those who spin the wheel to take 10 minutes to consider what it would be like to experience another’s identity – Black, Muslim, elderly, transgendered, bankrupt, and so on. Every wheel they have placed they have declared property of the city.

“I want these to be done in collaboration with the city, not vandalism,” he says. “I’m not fooling myself; I think it’s unlikely to happen, but it definitely sparks the imagination. We’re playing with the concept of authority. It is a blend of satire and activism.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I don’t have a set plan for every time I collaborate with someone. I think it will be different every time. I have many forms that are either done through collaboration or from getting feedback from people. I think in general I don’t see my art as mine. I think I am very lucky to now recognize how I am inspired by everyone who came before me, so I don’t necessarily take credit for most of my work. All my books are labeled “Property of Humanity.” I think a lot of troubles in the world come from people saying “this is mine.” Obviously it’s me who started it and who created most of the stuff, but I don’t see it that way.

(2) How do you a start a project?

Usually the idea comes from either something that’s very intuitive and it kind of sparked out of other conversation, and sometimes it comes from a need, someone told me that I should do – people asking, “Why do we celebrate people in sports and why don’t regular people get trophies?” And then I give it intent and form.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

Someone can donate to support my work if they like my work, or they can pay it forward and do something for someone else or donate to another organization. I don’t price any of my work. The emotional value is more important to me.

(4) How do you define success?

If my work is helpful to others and they find some compassion or social acceptance, that’s my definition of success.

(5) How do you fund your work?

Self-funding mostly, though once in a while I’ll get gigs. There are festivals that pay me to perform, and I get donations. It’s hard to find people who are appreciative of the work.

All photos courtesy of Ori Alon/Center for Supportive Bureaucracy.

[…] nags at them until they do something with it. Some, like service provider social practice artist Ori Alon, call it “intuitive;” others, like Tom Keifer, feel their ideas are […]