The Center for Media Justice addresses inequality in our media-saturated digital world

At a time when legitimate news sources are decried as “fake news” by our country’s political leadership and fear-mongering partisan websites that specialize is sensational stories with no basis in truth are considered primary news sources for many Americans, the need for an organization like Oakland’s Center for Media Justice feels more pressing than ever.

Major media historically has been a source of problematic representation, perpetuating negative stereotypes of underrepresented populations while at the same time creating further social divisions through lack of access. The Center for Media Justice (CMJ) seeks to address these issues of unequal representation and access in our media-saturated digital world.

“When I got engaged with CMJ I thought about changing media almost exclusively from the lens of representation, [but here I learned] that representation is only part of the larger system and the larger problem. We also have to look at who owns the infrastructure that distributes this media, who develops it and who guides it. The fact that we live in a media environment that is so heavily consolidated – it happened because laws were put into place that really allowed that to happen,” says Steven Renderos, who is a filmmaker, media producer, DJ, radio host, and community organizer, in addition to being the Organizing Director of the CMJ.

Renderos manages all CMJ’s campaign work and engages its national network of over 100 social and racial justice organizations across the country, MAG-Net.

“These are mostly locally-based organizations that cover a diverse set of users and constituencies,” he explains. “Some are more focused on cultural concerns, some do more base building, some are public access televisions and radio stations. We provide a vehicle for them to have an active voice at a national level around their focus issues that as a local institution alone they can’t fight for.”

Renderos came to CMJ through this network after doing research on the representation of Chicanos in the media while studying at the University of Minnesota. “Some of what came out [of that research] is just how inaccurate and stereotypical the representations are. A lot of [the media coverage] is focused on immigration and crime, using pejorative labels like ‘illegal immigrant’ and ‘alien.’ There is a certain bias baked in.”

He started as a community organizer right out of college, working with a tenants’ union for mobile home parks, mobilizing people in those communities to fight for things in their community that they wanted to change and also advocated for state policy. “I saw firsthand how media stereotypes and media coverage can shape the mind of policymakers,” says Renderos. “[There is this perception that mobile home parks are all] meth labs and trailer trash – the representation is framed in ways that they’re blights to the community. If that’s the image that comes to mind, policymakers are less likely to want to propose [supportive] policy.”

The mission of the CMJ is to “build a powerful movement for a more just and participatory media and digital world.” Renderos says that the principle that really guides their work is “the belief that everyone has a right to communicate, and that right should exist no matter what barriers are put in place.” The issues that CMJ tends to fight on social justice and racial justice tend to really intersect with media and telecommunications. Its primary bases are people of color and poor people, and the CMJ focuses on the issues in telecommunications that affect them most.

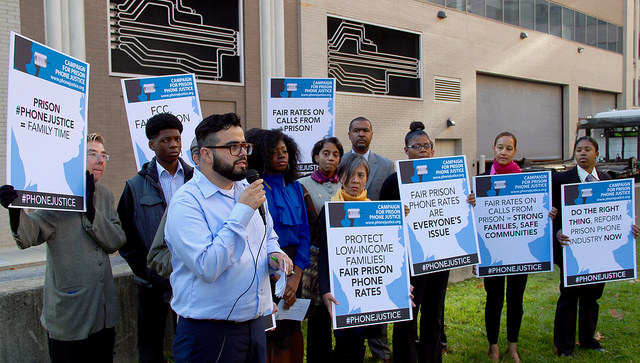

The first effort that Renderos campaigned for was lowering the cost of phone calls from prison. Having a cousin incarcerated in a state prison in New York, he knew on a personal level how cost-prohibitive phone calls from prisons are, further isolating prisoners from the outside world and making it nearly impossible for them to maintain contact with family and friends. One of his strategies was to have prisoners write letters to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and in the process further humanize these prisoners and what they struggle with in their inability to communicate being on the inside.

They also highlighted the story of Martha Wright, a grandmother who sued the Corrections Corporation of America over the astronomical phone bills she accrued trying to speak to her grandson while he was incarcerated. For 10 years her petition to the FCC to cap prison phone rates sat idle until the CMJ organized an event around this issue and invited her to speak at it. She felt her story and point of view didn’t matter to the commissioners of the FCC, one of whom later became one of the strongest proponents of reform on this issue.

“Stories matter,” says Renderos. “When we find creative interventions to shaping public policy interesting things can happen.”

Another effort Renderos fought for was expanding the low-income Lifeline program – providing a discount on phone service for qualified low-income households – to include broadband Internet access.

“We look at how we can protect voices online,” he says. “We also fought for net neutrality so that all people can have an equal voice online. We saw through Black Lives Matter and through the fight at Standing Rock again and again just how powerful a tool the Internet can be for organizing.”

While the CMJ has been on something of a policy reform “hot streak” lately, Renderos is aware that’s probably coming to an end with the current administration.

“It’s not really a site for change right now; it’s a site to resist,” he states. “Ultimately the ideal that’s behind his administration is one that is praying on vulnerable communities. The same with the [newly appointed FCC chairman Ajit Pai], a former Verizon lobbyist who has a great deal of power that will really benefit the corporations he used to work for instead of the people.”

Renderos says that the CMJ sees a lot of potential opportunity around surveillance at the local and state levels.

“We’re pivoting to the realization that we have a white supremacist in public office that has control of a pretty wide-ranging [system of] public surveillance,” he explains. ‘Activists will undoubtedly be targeted, so we’re conducting digital security training with those communities to limit the potential harm around their communications, so they have the tools at their disposal to limit potential harm.”

He also says that the laws such as the Obama-era broadband privacy rule adopted by the FCC and then overturned by the new Congress are now going to the state level, where the CMJ sees more potential in being proactive in shifting policy around privacy as well as surveillance, limiting the harm that can be done through high-tech policing.

“The perspective we try to bring is that the issues we fight for are about people and they affect people in a number of ways,” Renderos says. “We’re looking at what ways our ability to communicate is now being used against us, like surveillance and the adoption of technology to things like policing, and what that does to really supersize the potential for violence and abuse by allowing law enforcement to attack communities of color and poor people through surveillance.”

He also sees further potential in holding tech companies – which tend to use a lot of rhetoric espousing ideals of inclusivity and equality – accountable for protecting their users’ data from being used for the purposes of surveillance and giving their users more power to control their own data. “We’re looking for companies to provide access to more secure data and more secure devices to protect community of colors and communities of activists from having their data surveilled.”

Renderos will be at IdeaLab on April 14 discussing these and other issues, and how the creative community has a role in shaping culture and how that cultural change impacts political change.

“Part of what has guided my thinking and my work is a quote from Bertolt Brecht – ‘Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.’ Media is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer to shape it. As artists, we have a role in responding to this current political moment.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I like to be transparent with the partners I collaborate with so that my needs as well as their needs are met.

(2) How do you a start a project?

At work, I feel like projects start me, as a DJ I draw inspiration from what’s around me. Right now I’ve been listening to Erykah Badu’s “But You Can’t Use My Phone” Mixtape which features songs with a focus on communicating. I’m working on mixtapes with a similar common theme around communication but crossing genres, languages, etc.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

My value and strength as an organizer is centered around the relationships I have. I work at an organization that hosts a network and in order for me to succeed, I need strong relationships with our members.

(4) How do you define/feel success?

For me it’s in the stories that emerge as a result of my work. In the campaign I led around lowering the cost of prison phone calls, I felt success when I got a message from a person currently incarcerated. They talked about how much lowering the cost of the calls means to their ability to call their family. That’s what success really means, how are we changing the materials conditions people are struggling under.

(5) How do you fund your work?

A lot of it is grant based but the members of our network also pay dues. Their dues helps to resource their leadership when we host local events or convene our members.