Photographer Xavier Tavera documents the Latinx community from one border to the other

Xavier Tavera remembers picking up a camera when he was 11 or 12 years old and fell in love with photography immediately. To this day, he says, that “magical feeling” he gets from photography still hasn’t gone away.

His family immigrated to Minneapolis from Mexico City in 1996, and after that his photography changed completely.

“Just the sense of being here as a Latino and as a Mexican brought some consciousness about who I am here, so I turned my camera to the Latino community here,” he says. “At first I was looking at the Latino community as a subculture, but later I started trying to bring some awareness to that same community and highlight their voices.”

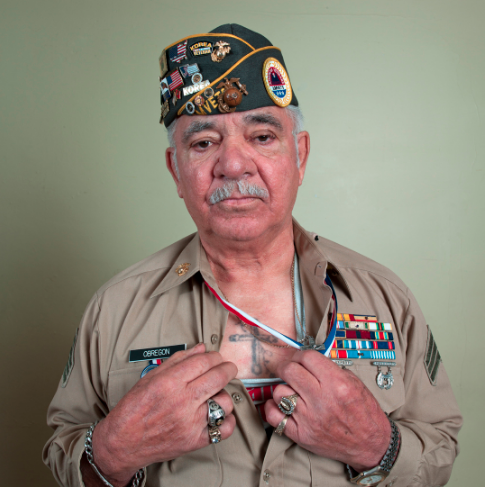

He started a project five years ago documenting Latino and Chicano veterans, taking large-format portraits as well as conducting interviews to collect their stories.

“Right in the middle of it I was interviewing and photographing them and I thought, ‘Who in the world is going to be interested in this stuff?’ Because their stories and what they’ve done is quite interesting, so I printed and packaged the whole thing and gifted it to the Minnesota Historical Society so that all the material will be accessible to people.”

Two years ago as he was working on his thesis for his MFA at the University of Minnesota, he and several million people across America were shocked by the results of the 2016 election and then by the actions of the current administration.

“I thought, ‘Well, I have to do something that reflects that concern,’” he says. “A plague that has marked most Latinos living in the United States is the notion of the border, whether they were born here or not. It’s so extremely politicized. So, I felt that I have to go there [to the border] and look at it myself to try to understand what this notion of ‘the border’ means.”

So Tavera started at the border between San Diego and Tijuana and traveled across the U.S. to where the delta of the Rio Bravo pours into the Gulf of Mexico, crossing the border and speaking with and documenting people on both sides. This ongoing project is called simply Borderlands.

For part of this project, Tavera has been imposing drawings on top of the images, which he says is really just him proposing alternative ideas.

“I hear all these extreme politics around the border, or people chanting, ‘Build a wall!’ Why don’t we build a bridge or build a tunnel instead of a wall? Why not build a table and essentially approach it and have a meal with people on the other side of that table? How would that look?” he asks. “These are things that will never happen; I’m just proposing ideas. What if there was a little shack casting a shadow on the border? What kind of conversations would people have under this shadow?”

Most of his projects are portraiture because, he says, he is interested in the intimacy it creates with people, but for this project he is doing landscape photography which he had done very little of previously.

“The history of landscape photography in the U.S. is very interesting. It came about not because of the beauty of a place or the exoticness of the lands or the beauty of the light. It came to be as a colonizing document,” Tavera explains. “British ships would arrive and bring one artist with them. As soon as that artist stepped onto the land he would start drawing or painting the landscape of the land, so when they went back they could use it as a document of ownership, claiming, ‘Everything you see here is ours, and not only that but it’s also for sale.’ The initial beginning of landscape art in the U.S. was completely a colonial endeavor.”

With that in mind, Tavera goes to these borderlands and photographs the landscape where there is a wall or a river dividing the land, with a very intentional focus on the border not as a topography but as a manmade idea.

But, he laughs, he can’t get away from taking portraits because that’s what he enjoys the most, so he crosses back and forth across the border talking to people on both sides and documenting their stories and their lives through portraits.

“The interesting part of photography is not clicking and printing and exhibiting them. It’s talking to people with that vehicle of access that is the camera,” he says. “If I go over here to the bus station and ask people what their lives are like, where have they been, and why are they here, they would look ay me like I’m crazy. But if I arrive with a camera, there’s a purpose. [People feel more comfortable with it.] Just by having a camera I can ask questions and people open up to me and tell me very intimate stories. That’s what I really enjoy—at the end of the day, yeah, I have a picture of them, but the whole experience is what I enjoy the most.”

While there are geographical differences all along the border from one point to another, Tavera is using this project to observe what is similar about the borderlands.

“The two sides share a very similar culture,” he says. “They have two languages and share similar food and music that is very specific to the borderlands. There are a high percentage of people living on both sides of the border who are living under the line of poverty. With the exception of El Paso, San Diego, and a few other cities, poverty is shared across the border. I think those similarities are quite interesting.”

One of the most glaring differences to him, however, is the way the border looks on one side compared to the other. He says that if you’re in El Paso looking at the border, you’ll see a fence that just looks like a highway retaining wall. But if you’re on the other side of the border in Juarez looking towards El Paso, there is “an insane amount of concrete” along the disappearing Rio Grande, and the border wall is heavily patrolled. The aesthetics are completely different and the message is clear: “You are not welcome here.”

Similarly, on the San Diego side of the San Diego-Tijuana border, a person can simply walk right in to Mexico through a turnstile. But on the Tijuana side, crossing back into the United States is a completely different, intimidating, and interrogational experience.

“It’s interesting for me to point this out because of me migrating to the U.S. and all of sudden having an interest in this,” says Tavera. “When I was in Mexico City I was far away from the border [and it wasn’t something I thought about]. Now I’m way on the other side of the country, only six hours to the border with Canada, [which is treated much differently than the border with Mexico]. Looking at it from this angle, it is quite different. I really believe that this notion of ‘border’ has marked the Latinx community in a radical kind of way.”

Furthermore, he says the whole idea of being “Mexican” is diluted in Mexico, but in the United States a person from Mexico is defined by little else.

“Here, I’m Mexican; I’m a person of color; I have all these other labels. And that’s why I make a point of doing work on the Latino community here.”

This is an ongoing project that will be a few years in the making. In the meantime, Tavera also has two projects currently in the works with Centro Tyrone Guzman, the oldest and largest multi-service Latino nonprofit organization in Minneapolis.

One project he is working on through the organization is in partnership with ACT on Alzheimer’s, which helps families impacted by Alzheimer’s, providing them with resources, guidance, and support.

Twice now he has worked with Centro on a project photographing five or six families in which a member of the family has Alzheimer’s. Tavera photographs the families, including the person with Alzheimer’s, and then gives the families the portraits he takes.

“It’s very interesting to see how they gather, how they come dressed up for the portraits. They see this as something important for their family,” he says.

The program is designed to assist and support members of the family who are taking care of the Alzheimer’s patient, or are in any way part of that person’s life, to let them know that there is a place they can go for help and they are not alone. The learning curve in dealing with this disease is steep and it can be very isolating, even in a culture with very strong commitments to familial bonds and responsibilities.

“There’s usually a member of the family that takes care of the person, and the amount of care they need varies a lot,” he says. “Some of them are in the beginning stages so the amount of frustration involved is different than a person in later stages. Sometimes the daughter-in-law is the one who takes care of the mom, making sure she’s fed and clean and taking her medications, so other members of the family don’t see the experience of taking care of a person with Alzheimer’s as a problem because they’re not living daily with the person and the disease. This is a place where they can come and discuss those issues.”

Tavera understands intimately what it is like to live with a family member with Alzheimer’s—his father has Alzheimer’s.

“It has been tough, but of course not as tough for me as it has been for my mother and sister who are living with him in Mexico,” he says. “But I can’t have the conversations with him we once had. I can’t ask him questions about his youth as I once did. I can’t record his stories. The problem is now mine: acceptance of the issue is the problem. He’s happy and healthy; it’s my issue. I’m now regretting not having more communication with him because now all those stories are gone. I feel for the families at Centro because I’m in a similar situation.”

Another project he worked on with Centro is currently being exhibited at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA). For this project, Centro organizers asked a group of elders to bring in an object that is relevant to them and their culture, which Tavera then photographed.

“These are people from Colombia, Santa Domingo, Mexico, Cuba, and all over Latin America that ended up here in Minnesota,” he explains. “What does this object mean [in regards to] their cultural background? Why do they keep that object? Why is it relevant to their story here in the United States?”

Tavera now has 47 objects he has photographed—originally it was only going to be 10, but he kept getting more and more requests and would go to Centro every weekend to take more photos.

“There’s a huge range of things they bring in, from knick-knacks in their house to cultural items that they use daily, like items they cook with or garments they made.”

One gentleman from Mexico, who has been in this country for over 40 years, brought in an old hairbrush.

“Everyone else was bringing in a flag or something more representative of their culture, but he brought a brush,” Tavera says. “He said it has brushed the hair of three generations of his family. It was his father’s and he has kept that brush and used it on his daughters. I thought this was so interesting. When you see the object, it’s just this brush. There is nothing special about it. But it has been used in this intimate way for three generations and he still uses it with what little hair he has left. It has been used for parties, for celebrations, for funerals. The amount of history in that single object is incredible.”

For his next project, Tavera would like to document all of the old barrios in the United States—the soon-to-be-gentrified neighborhoods of Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan, Little Havana in Miami, and Boyle Heights in L.A., as well as parts of New Mexico and other areas.

“This would look at all the oldest barrios that exist in this country where there’s an inland echoing of the border that is very interesting,” he says. “Right here in St. Paul’s West Side, [a predominantly Latino neighborhood], there is Lake Street, and on Lake Street we have the same kind of culture clashes that happen at the border at school, at work, on the bus. I think it’s interesting to see that culture clash happen in different places that aren’t the border, [especially places so far away from it]. It’s also a reflection of what the border is, and how it is more than just a geographical location.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

For me, art-making has a history of being very personal, but for 19 years I’ve been collaborating intensely with a friend of mine, Douglas Padilla. We started 19 years ago when there was nothing around Latino representation, when there were no nonprofits dedicated to the Latino population. We decided to start a group called Grupo Soap del Corazón (“soap of the heart”) and at least once a year we would make an exhibition or workshop or some activity that has to do with Latinos. It is not exclusively Latin—we have Native friends and mainstream friends that we invite to participate with us—but it is an intensive collaboration to feature work by Latin people. They’re messy and conflicted, but I do believe collaboration is a very primordial part of our practice.

(2) How do you a start a project?

Every project is completely different. I don’t have a process of how things start. Sometimes it happens with an event. For example, Doug Padilla lives part of the time in Pepin, Wisconsin, about an hour and a half from Minneapolis. At the start of the 2018 gubernatorial campaign, a guy that owns a café over there went to open his café in the morning and found a sign saying, “Mexican go home.” It’s a very small town, a tiny rural community. You wouldn’t believe this tiny community would have this hatred. So I said, “Let’s do something there. Let me go around and take portraits of dairy farmers and dairy workers and display them not in a gallery or museum, but in a church or a community center. I’m going to photograph brown and white people and do it the same way.” 97 percent of dairy workers in Wisconsin are Latino, so I’m super curious about the relationship white dairy farmer have with these others. How are they seen as the “other?”

The veteran project started in Mexico City with WWII veterans. The U.S. sent hundreds of thousands of Mexicans to WWII, but Mexico sent only 300. I was able to photograph 12 of the 35 remaining.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

I used to tend not to rely on grants and funding like that, I would just do the projects on my own. About 15 to 17 years ago I got my first grant and I got super scared. I got a McKnight grant for photography and was paralyzed by it. I didn’t do anything with it for a week until the director of the program had to call me and ask what was going on. I kept thinking, “This is a lot of responsibility. It’s not free money because these people think that what I do has some sort of value, if not monetary than cultural value, and it’s a huge responsibility.” I’ve got used to it and have had other grants since then, and all this funding is super helpful for what I do.

I’m not sure I can consolidate my work into a monetary value because it has to do with stories and the history of the community, and that’s hard to ascribe a monetary value to. I would rather that the Minnesota Historical Society has 60 images of mine and that will provide a way for people who want to know about these veterans to see them, and I find more value in that than in me selling portraits to an institution. How can I monetize suffering or the trust people put in me to tell these stories? On the other hand I’m always super happy when I receive a grant that can help do that projects I do.

(4) How do you define success?

That is so subjective. I can for sure tell you that I feel more reward when a family that I’m gifting a portrait to, like the family of the Alzheimer’s patients, are extremely moved by seeing them and that will manifest as crying. I’m not sure having acquisitions in a museum or having a show equates to success. Those are just a few of the many ways to share the work. At the end of the day you know if people are digging it or hating it. It’s hard to explain or even comprehend what success means. If something is clicking and people are reacting to an image, or when I have a show in rural Wisconsin and the farmers are coming to see themselves in those pictures, and they made the effort to travel half an hour to see those images, maybe that’s successful in that way.

(5) How do you fund your work?

Most of the projects that I do I start just by doing them with no funding and if I see that it has potential then I start to ask for funding. Sometimes it comes in the shape of a grant, or if an institution is interested in the material then I will ask them for funding, but all of them start with an idea that I start by going out and photographing to see if it’s going to work or not.