These New Orleanians use poems and portraits to create deeper connections in their community

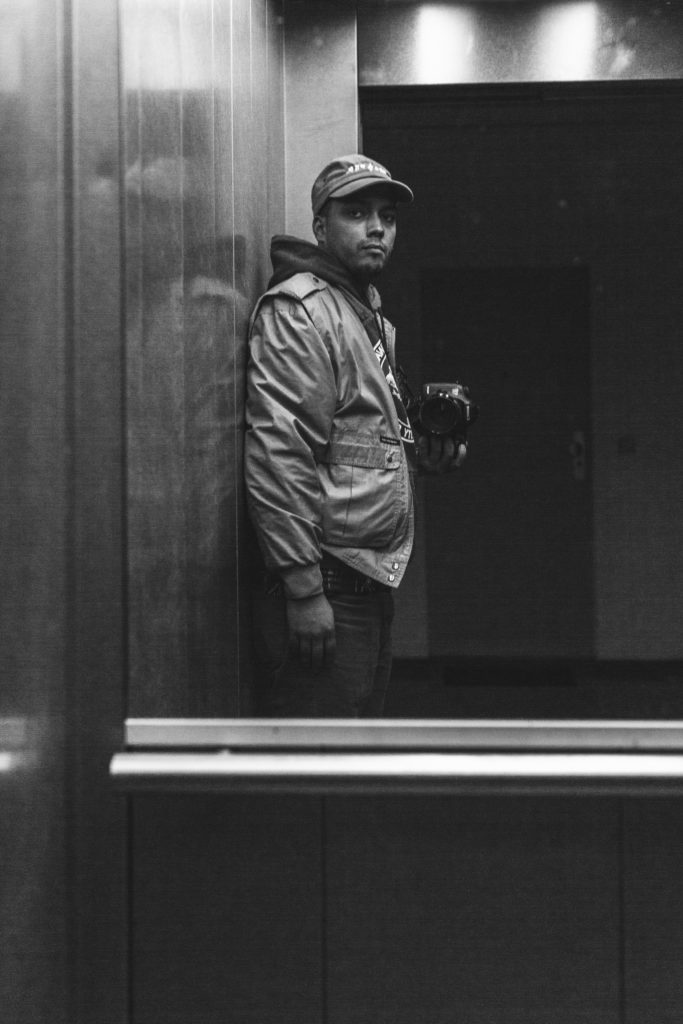

Jose Cotto and Christian Davenport come from very different backgrounds, and both have very different practices: Cotto is an architect, educator, and photographer raised in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Davenport—aka, “Cubs the Poet”—is a poet, illustrator, and speaker born in Baton Rouge. Both now live and work in New Orleans, where they met just a few years ago and now collaborate on projects where their different approaches towards fostering connections with others dovetail beautifully.

Growing up on Worcester, Cotto was first exposed to art through taggers and graffiti artists. For him, art was a way to live beyond the environment he was in; it was an escape from the place he lived, but it was also a way to look at and think about that place differently. He says he was creating art from a young age, but it didn’t become a regular practice until he picked up a camera. At that time, he was attending UMass Amherst, a much different environment culturally from the one he grew up in (the school being rural and mostly white).

“The city I grew up was very diverse and the schools were very diverse,” Cotto says. “UMass was a bit of a culture shock for a lot of reasons. No one in my family had gone to school, so I had no idea what that environment would be like. Being a photographer gave me the opportunity to document that time and gave me images that I could revisit whenever it felt necessary as a means to understand what that time was like. I started documenting my environment there to understand how it differed from the environment I came from, but also what the overlaps were as well.”

He began by working mostly with film, and while his practice today is all digital, he feels that his background in actual film taught him to be much more intentional in his photography, and also lends his work, even in digital, a certain tactile nature.

“It has made me way more critical as a photographer and pushed me to develop a means of editing before I ever even take a photo,” he explains. “There’s a lot of editing that’s happening all the time as I move through the day, and I’ve tried to get to a point where I only raise my camera when I feel the photo is necessary.”

Cotto moved to New Orleans in 2012 to attend Tulane University for his master’s in architecture, but also because he just wanted to live in New Orleans for a while. He had family from the city and had visited previously, and found it to be a culturally and creatively rich place. He has been photographing consistently throughout the time he has lived there.

“A lot of my photography work has been about this interesting back-and-forth of documenting the city and working with other artists as a way to establish connections and roots in the city, but also being mindful of the fact that I just moved here only seven-and-a-half years ago, and there are a lot of folks here doing amazing work as well,” he says. “It’s been interesting to me, figuring out where the output of this practice should live, so a lot of my intentions or role as a photographer in the city has been working with folks like Chris and others around the city, plugging into the existing infrastructure with the folks already here on the ground doing things and adding my perspective to whatever that is.”

Cotto does a lot of portraiture work, but he keeps it very informal and tries to be as hands-off as possible. He approaches portraiture work as a documentarian: “My role is to show up to a place and find the photos that are supposed to be taken, and not stage something to create an environment to document.”

Davenport says that Cotto has a way of asking people questions that get them to a very personal space—they’ll close their eyes and spend some time thinking, sometimes several minutes, and once they’re fully present in that moment in their minds, then he takes the photograph.

“You realize you’re in this intimate place in your mind but you’re also in public,” Davenport explains. “One of my neighbors sat for probably 12 minutes with her eyes closed, but he held his pose and allowed her that time.” He is impressed by Cotto’s process as an artist and creator himself: “We’re so involved with what we do that we never get to step out and watch it as an observer.”

Cotto and Davenport met about four years ago, and in the last two years Cotto started doing these one-on-one intimate portraits, often at events where both he and Davenport are working. The portraits are done in a stripped-down studio setting and usually revolve around a prompt or conversation.

“Part of it for me is trying to achieve a sort of documentary-style street photo, trying to get that feeling when you can sense in an image when someone isn’t necessarily aware of the camera, but in a studio setting where people know they’re being photographed,” he says. “The idea is giving people the freedom to just reflect and go to a place [within themselves], then creating an image that cements that journey for them through the expression on their face and emotion in their eyes, so that they have a reference point for wherever they went to in their mind.”

Cotto also edits and prints the photos in front of the people he photographs so they see the whole process, and also the full extent of how he sees them.

“They get to watch me edit their photos and that exposes me a little bit; part of it is me trying to meet people where I’m asking them to go—a memory of feeling an emotion in it rawest and purest form,” he says. Over the course a night he might document 40 to 50 people and get a range of emotions. “The work has essentially evolved to be this therapy session in a lot of ways. It gives people the opportunity to get something off their chest without having to say any words.”

The prompts are usually about life experiences. One of his sessions, inspired by a show focused on Rodney King at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, asked people to recall their first interaction with law enforcement.

“I’m trying to push people to be a little bit uncomfortable,” he says. “I don’t buy into the notion that my job as a photographer is to make people comfortable in front of my camera. For me, my responsibility is to document truth.”

Davenport, who calls himself a “modern day wordsmith,” is a working poet, and the term “working” here feels important: poetry is what he does for a living. “Poet” is his profession, and it is through his work as a poet that he gets paid. This is no small feat, as most poets would likely agree.

He is the inaugural Poet Laureate of Baton Rouge, working closely with the Arts Council and mayor to create programming and workshops based around poetry and community work. He is also a public speaker and will soon be a published author—he is currently working on a book that illustrates his poetry with his own drawings.

Davenport was born in Baton Rouge, but his family moved to Frederick, Maryland when he was still a young child. When he looks back, he believes he was born to be a poet: he remembers wanting to express himself with words before he had the words to do so. Throughout his life, he attended schools where each was a very different environment from the next: he went to a private elementary school that was predominantly Black, a middle school that was predominantly Latino, and a high school that was predominantly white.

“I got to see how people existed within [the school setting] and it really opened up my eyes to people,” he recalls. He moved to New Orleans to attend Dillard University where he studied marketing…mostly for the sake of his parents. Not that they put any pressure on him; his dad was an entrepreneur and very passionate about business, and he feels his parents were good parents who loved him and raised him well, so by pursuing a degree in marketing he felt that he was honoring them in some way.

But he remembers sitting in classes and thinking things like, “What does this word mean? Why is this relevant? Why does this matter? Yeah, you need to teach me a marketing plan, but why?” His advisor suggested he study psychology, but even in his psychology classes, learning about behaviorism and the psychological theories of all of these great thinkers in history, Davenport was restless.

“School is set up to learn these ideas [from other people] so you can learn to express what you want to say, but as I was growing up I had already developed the perspective I wanted to express. I was learning about these theories that other people had developed for themselves, and I wanted to learn how I could do that.”

During summer break after his junior year he was back home in Frederick and fell asleep in the basement with the TV on. He woke up feeling compelled to write a poem, and he wrote the poem “Do You Like Poetry?” in red cursive ink. Prior to this, he had never written any poetry or even so much as taken a poetry or creative writing class; in high school, his creative writing output consisted of some “borrowed” lines from Jay-Z.

He decided to take this poem on the road, so to speak, sitting outside in front of a closed restaurant on Market Street in downtown Frederick and asking people if they liked poetry as they passed by. He read his poem to anyone who was receptive to hearing it. He found that reciting the poem helped him to see it through their eyes and learn what they liked and what they responded to.

Davenport spent that whole summer reciting this one poem, and people took notice. One woman approached him about reading poetry at her vintage furniture and women’s apparel store; instead of taking payment for his time, he asked to take a vintage typewriter he spotted inside the store. That typewriter has become a very visible, ever-present part of his practice.

He returned to New Orleans that fall and noticed the artists and musicians on Royal Street. At this point, he decided it was time to be a poet. Every day he took the bus from Dillard to the French Quarter and would set up on Royal Street with his typewriter from 11 a.m. to 1 a.m. writing poems for people who sat down with him.

“I did it every day like a business,” he says. He would either have a sign out asking people to stop and sit with him, or he would ask passersby the very question that ignited his passion: “Do you like poetry?”

From there, he would ask them what they wanted a poem about. Maybe it was a person who wanted a poem for their spouses, so he would ask what they love about their spouse or how they met. If they didn’t have any specific ideas, he’d ask them questions like, “Are you a window or a door?” or “What’s your favorite season?” Even, “If you had to live with only one sense, what would it be?”

And he would write. He learned to write under pressure and on the spot. He also learned to navigate the question of cost—in typical busking culture, people watch someone perform music or create art, leave a couple of bucks, and move on. Davenport initially accepted donations of any amount, which turned into giving poems away essentially for free. Over time, he learned to charge a fair amount for his work and also be learned to be comfortable asking for it.

“On the street or at events people still have this awkwardness about money or the exchange of value,” he says. “It takes a moment to get back on topic, or diminishes what we’re trying to build. If I can get all that out of the way, what can we create?”

Now if he sets up somewhere like St. Roch Market, he posts a price sheet: $50 for a custom poem; $10 for gift cards or $25 for a pack. “I also had a dream that I woke up with $43 million so let’s put that out in the world.” Done!

Davenport feels his responsibility as a poet is to document his view with poetry, and also to help everyone realize they are poetry. He sees every person as a poem, and says that he does these events and busks on the street for a living and because it’s his life’s purpose.

He still uses his trusty old typewriter, and when people ask him why—a tablet would certainly be easier to carry around—he explains that it’s because with the typewriter, it’s just him and the other person in that moment. There is no opportunity to Google different words or make any edits.

“Whatever my vocabulary and that person’s vocabulary is, that’s what we have,” he explains. “That’s why I’m so big on people giving me their words and that’s where my psychology background comes in, through free association. Then I build a story off of words.”

Now people hire him to write for events like weddings and art exhibit openings. He even went to Nashville for the opening ceremony of an architecture firm. He likes doing weddings because he gets to hear all about the couple from their family and friends who love them and gets a sense for how these people love each other. Next, he would really like to do a funeral.

“I think doing a funeral would be amazing,” he says. “People would get a sense of how this person affected people’s lives. [When someone dies], people don’t usually sit with those emotions or talk about them. As a poet, I do, and I can guide that sense of intimacy and ask those questions that really get you to think.”

Cotto says that Davenport is giving people space to sit with things. “A lot of the synergy that exists between our work and approach revolves around the reality that all of us are constantly moving towards something. It’s very easy to forget during that process that where you are right now is also important.”

Davenport adds, “We really provide a space for people to really sit and think about these things. There’s a nostalgia that comes with seeing a typewriter or a camera, and the process of printing a picture after it’s taken. I think that’s why people are so attached to the things we do, because they can actually see that process.”

For the past year and a half, Cotto and Davenport have been doing joint poetry-and-portrait sessions at events—Cotto will take a person’s portrait and print it out, then Davenport will sit with that person and type a poem on the print itself.

Last fall, they submitted a proposal for a public art project in collaboration with Paper Monuments, an organization based in New Orleans that has been active in the conversation about monuments in the city, specifically getting the monuments of Confederate generals and white supremacists removed. Paper Monuments issued a call for proposals for projects and stories about what a monument in the city should look like. Both Cotto and Davenport felt an immediate gut reaction to this particular call, that the people in the city are monuments, and designed their project with that idea in mind.

“There are a lot of conversations about how physical monuments are designed and erected, but nothing about how the people in the city are the monuments, just as people are poetry,” says Cotto. “New Orleans is New Orleans because of the people, not because of any buildings or monuments, so we wanted to really focus in on that.”

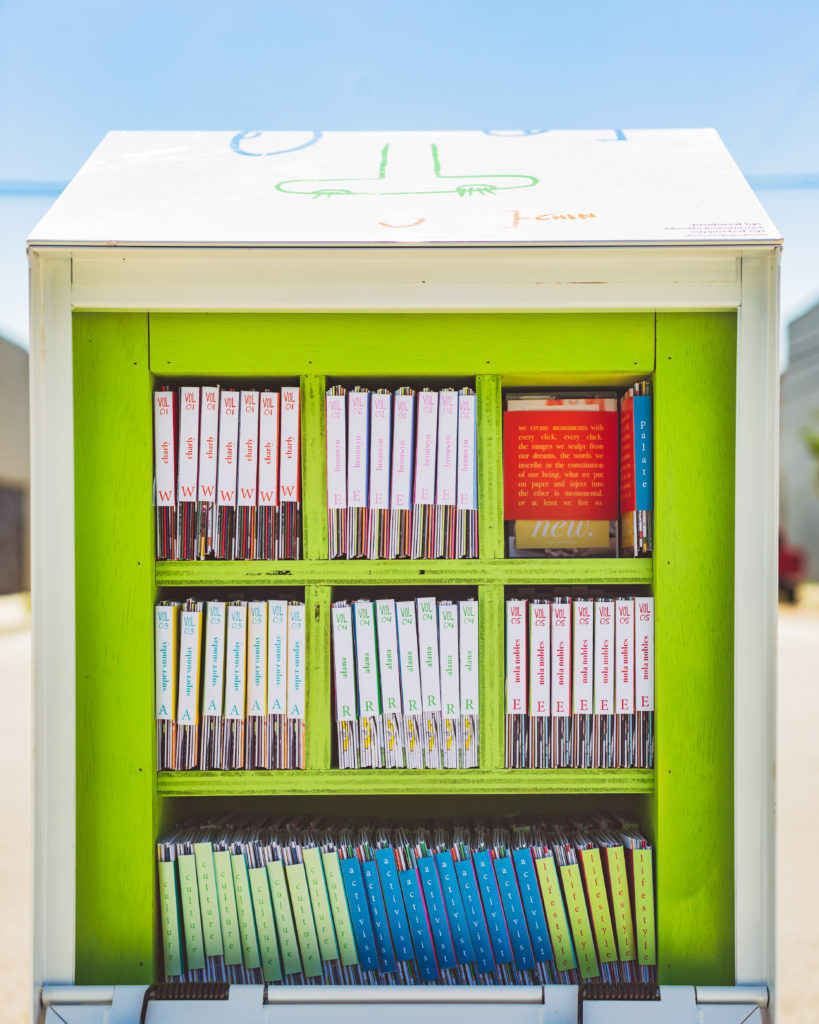

Their project was called New., a zine project with the tagline, “We are Monumental.” The goal with each issue was to highlight a person, place, or event, and focus on the people creating culture in New Orleans. The idea behind each issue was to push their portraits and poetry even further, zooming in on the details of the person’s life. The poems written became the storyline throughout each zine, and then the images and poetry share space on the pages.

“We were rejecting the notion that we needed a physical intervention as an answer to what a monument should look like and instead engaged with the folks who are around us on a day-to-day basis,” Cotto explains. “Now you have some insight into who Charly is, what he does for a living, the things he loves, and what he spends his time doing. The idea is that people would pick this up and be compelled to want to engage this person.”

They did a run of five zines in total, with 32 panels to each zine. The zines themselves were very playful and interactive, each made out of one single 13×19” double-sided sheet of paper that folded into itself like an accordion.

“It’s a tactile experience,” says Cotto. “We spent a lot of time on what we wanted the experience of engaging with this thing to feel like. It pushed us both to consider how our respective mediums could go beyond what we were doing with them by presenting them in this different format.”

Cotto has always felt like there is too much of a “behind glass” approach to photography—the idea that real photography must be experienced in a gallery in a frame behind glass. For him, his earliest memory of falling in love with photography was seeing the photos that lined his mom’s staircase, and all of her family photo albums.

“I’ve always been interested in finding more ways to share images with folks that strips away these layers of hierarchy from museums and Art-with-a-capital-A,” he says. “With the zines, people hold these things in their hands. They flip through it. It’s a precious document because of the stories in it, not because of the object itself. For me, that was one of the more revealing parts of this process—getting back to the more tactile quality of the medium.”

Davenport says that for him, it gave him another, or perhaps fuller, understanding of how to write poetry to tell a story.

They made the zines easily available to the public in the spring of this year by purchasing some newspaper distribution bins, building out shelving, wrapping them with illustrations Davenport had made, and placing them in three different locations throughout the city. They printed a limited run of 100 of each zine, and they just kept filling the bins until they ran out. That took about two days.

As we head into a new year, and a new decade at that, Cotto and Davenport are both thinking about what they’re going to focus on next. Cotto says that the last year has been pretty slow for him in terms of photography production. He currently has an archive of about 150,000 images and he’s been doing the “daunting and crazy” task of going through it all. His goal is to work on a book that will look back on the last ten years to the time when photography “started to occupy more space” in his day-to-day life.

“The idea is for that book to show the growth and evolution of that process,” he says. “There’s no theme or direction in how it’s going to be curated; just time.”

He hopes to have an artist’s proof by summer 2020 and then have a number of copies that he prints and hand-binds himself, hearkening back to those very labor-intensive, tactile early days of his photography when he was sitting in a darkroom developing prints.

Aside from his photography work, Cotto is very much involved in the design and architecture world, currently working as the Collaborative Design Project Manager at the Tulane University School of Architecture. He was previously the Director of Design for Arts Council New Orleans. He wants to bridge those two worlds of his—photography and design—more intentionally. A project he will work on in the coming spring is a step towards connecting those two worlds, documenting people’s experiences with water in New Orleans as part of larger conversation of living with water, and the ever-present threat it poses, in the city.

He will also work on a project with another Salzburg Young Cultural Innovators Fellow who lives in Baltimore on a series about the families of people who are incarcerated and how incarceration impacts people beyond just those who are locked away.

Davenport plans to release his book of poems and illustrations called What I Did with My Free Time in 2020. After a year in which his work took him to Los Angeles, Nashville, Philadelphia, Salzburg, and Stockholm, he would like to have some sort of tour or itinerary every month where he travels to different cities to write poems for people.

“I want to be able to write as many poems as I can for as many people as possible, like McDonald’s,” he laughs, referencing the fast food giant’s now-iconic “billions and billions served” sign. (He has a running tally of poems written on his Instagram account.)

He would also like to create a poetry album that would have either the voices of other people reading poems he’s written or his own voice reciting his work paired with jazz music and him typing in time with the band on his typewriter.

“I really just want to get out, travel, and showcase my work in as many places as possible, but with intention,” he says. “I want to write poems, recite poems, create books, get outside of New Orleans and spread the word of what I’m doing.”

All photos by Jose Cotto.

Jose Cotto and Christian Davenport are both Salzburg Global Fellows (2018 and 2019, respectively), and both attended the Salzburg Global Forum for Young Cultural Innovators in 2019. Springboard for the Arts Associate Director Carl Atiya Swanson is also a Fellow; read his reflections on the 2019 Young Cultural Innovators Forum here.