Krystal Ramirez’s text-based work highlights the invisible labor of marginalized communities

When Krystal Ramirez was in art school studying photography, she didn’t think about who she was making art for. She didn’t question who her influences were, those Very Important Artists that defined their respective movements and comprise all of “art history.” She didn’t realize that all those influences were white men, and that, by extension, all of the work she was making was catered to white men. That realization came a bit later.

“When I was in school there was no Instagram. It was in the early days of Facebook and Myscpace was still around. The world we live in now didn’t exist yet,” she says. “The art world is 70 percent white men, but you didn’t think about that then. Kids today are having conversations that I’m just now learning about and just now talking about.”

There are certainly advantages to the hyperspeed bombardment of information we now face online everyday, and those include a newfound cultural “wokeness.” Kids today might not know how to function without their smartphones, but they’re also much more informed about and in tune with cultural and social issues that may not have been as obvious or immediate to previous generations.

“When I was in school I didn’t realize all of my influences were white men,” says Ramirez. “When you’re in school, you’re influenced by whatever you’re taught. When you’re in school, you’re making work for a white audience because that’s what you know and see, and for most of the work in academia that’s the audience. I just thought I was making work that I liked, but now I’m aware of that and my work is more critical.”

It has only really been over the last couple of years that her work began to take on more social and political tones. Before that she hadn’t wanted to be “pigeonholed” as a “Latin artist” or a “female artist,” but, she says, “That’s just how the world works. No matter what kind of work I make people are just going to see it through those lenses.”

Ramirez is, at her core, a photographer, but while she was in school she studied everything, including sculpture and printmaking. Lately she has been doing more work in mixed media and has found herself drawn to printmaking and exploring more text-based work.

Her first “intentionally political” piece was called I Want to See, a 12×15-foot banner installation made from Bible paper stitched together with thread. “I want to see brown bodies” was handwritten in typography across the pages. The piece was accidentally destroyed in its first placement, so she had the opportunity to remake it—giving her the chance to improve upon the original, she says, as well as think more about why she made a huge transparent piece with this particular message, and why she liked it so much.

She thought about the “minimalist” movement in art, how it was basically white male artists imposing their white masculinity by creating large, destructive objects that “get in your way.” And she thought about her own piece and found in interesting that she herself made work that could fit within this cannon of white male minimalist work that people know and believe they have to like.

“Minimalism in the art world is a very masculine thing,” she says. “Historically it was men making these large objects and structures that stood in front of you and were this presence blocking you, so I made this hanging piece that looked like a big textile rug or panel blocking you, but once the light hit it the paint and paper are thin enough that you could start deciphering letters. Maybe initially people didn’t know it was made by a brown person or by a woman, then were surprised when they found out later.”

For this piece Ramirez says she was specifically influenced by Carl Andre, an American minimalist sculptor who, in addition to his large-scale sculptural work, created text-based poems on a typewriter using repeating letters.

“It’s very masculine, using a machine that looks very mechanical and sterile, and I wanted to do something similar but make it more feminine,” she explains. So she took very thin paper, the kind used for printmaking or religious books, and layered it to give it texture, sewed the layered pages together, then hand-wrote the typography—an intensive amount of “invisible” labor.

“There was all this labor involved that may be thought to be more feminine-identifying, things like sewing and handwriting. Even though historically men were the ones hand-writing most of our recorded history, today handwriting is associated with a more feminine touch.” She adds, “I thought handwriting was more of a non-gendered thing, but reactions to my work have been that it’s ‘so feminine,’ even when it’s not written in cursive.”

She describes much of her work as containing the “hidden labor” that women and people of color do—that labor that’s typically overlooked.

For her, touching on that issue of the hidden labor of marginalized people is particularly personal: she started thinking about this because of her parents, who are both immigrants and worked hard labor in blue collar jobs so that she could go to college.

“And I decided to go to art school instead of being a lawyer or a doctor, and I felt a lot of guilt about that initially,” she reflects. “When the work is all conceptual and there is little labor behind it, it’s such a privilege to be able to make something so philosophical and wordy that you have to have a certain level of education to even be able to talk about it. I was attracted to work where you could see the labor that went into it. I felt like it was more important to make something more laborious that was respecting the labor and work my parents did, even though that’s not my life—I’m not out there doing back-breaking work, but I think it’s important to have these conversations about the people who do.”

She says she hopes to not only respect the people who do that labor but also push people to do more of the “one-on-one labor” to actually have these conversations…and not just have them on the Internet.

“A lot of people are having these conversations on the Internet, but what do they do when they get off their phones and off the Internet? What are the real-life changes people are trying to make?”

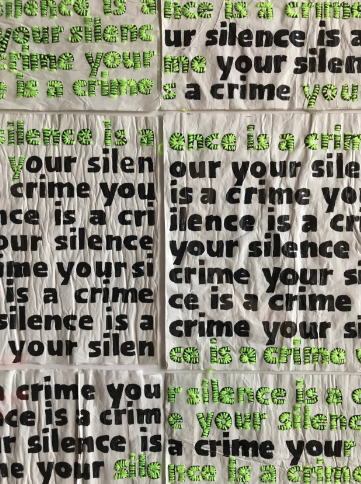

One of Ramirez’s pieces that speaks directly to this is called Your Silence is a Crime, another labor-intensive work with the words “Your silence is a crime” repeated on textured paper using black hand-written typography interspersed with occasional neon green knit yarn.

“This also brings up the conversation about people who are complacent,” she explains. “I’ve met a lot of people who talk about inclusiveness and intersectionality, who hold workshops to make protest signs, but can’t have a hard conversation with their neighbor or friend about respecting their Black neighbor or Mexican kitchen worker.”

She enjoys working with typography and graphics because she loves the process of layout and design, creating somewhat “hidden messages” that the viewer has to work for, forcing them to stop and actually look at the piece instead of casually glancing at it for two seconds.

“With Instagram and social media now, the world is so saturated with text art so I thought, ‘Let me make it harder for people so that they have to stare at it longer.'”

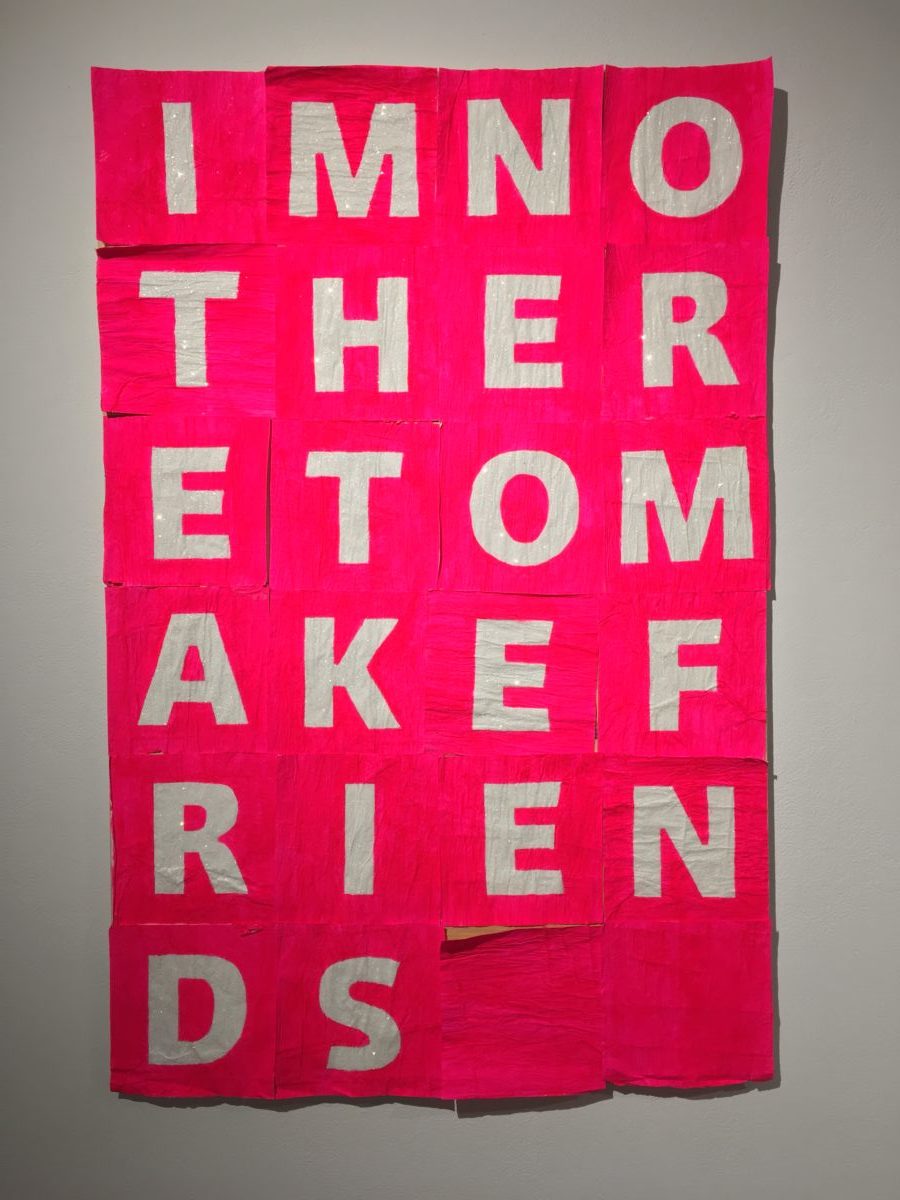

She has also been incorporating more color into her work, as with Your Silence is a Crime and another work called I’m Here, comprised of neon-pink paper stitched together that reads “I’m not here to make friends” in giant, all-caps, sparkly silver block letters—a collision of the masculine and the feminine with its strong, assertive message in bold lettering presented with stereotypical “female” colors and sparkles, and once again done in Ramirez’s labor-intensive method.

“I’ve been so focused on the minimalist palette, so this was the first time I chose such a bright, vivid color, which in itself says a lot about being a woman and feminism,” she says. “I wanted to choose a color that means something, and this hot pink is such a popular color right now with the Women’s March pink pussy hats and the Me Too movement protest signs.”

Especially in this world of Instagram, when all art is fair game as a backdrop for selfie-taking Instagrammers, Ramirez subconsciously avoided color, but she has come to see the use of color as being a more accessible entry-point into the art for people who might not understand the work conceptually.

“One of the reasons I started adding color to my work is because I try to think, ‘If my mom is looking at the work, is it something she’s going to be attracted to? Is it something my family could engage with, or my friends who aren’t engaged with politics or art?’ I think, with the work I was making in the beginning, art people were attracted to it, but I want to make work that isn’t just for art people.”

While her large-scale text-based installations have been prominent in her work lately, Ramirez is, once again, a photographer at her core. Lately she has been considering ways to use photography to explore the female gaze in her work. Though she says she’s still working out her ideas, she is very much interested in the male artist/female muse relationships that have dominated art history and the way women have been objectified by both men and women (who subconsciously create work for the default audience of privileged white men, as Ramirez found herself doing), as well as how women might objectify men.

Even in her experience as a commercial photographer in Las Vegas, she would show up to shoots and observe how much differently she was treated than her male counterparts: men treating her like the assistant and waiting for “the man” to show up, male chefs asking her if she needed help figuring out how to shoot food images, men asking her if she knew how to use her equipment or if she was sure she was posing or lighting them correctly.

“At least once a week this happened,” she says, which probably comes as no surprise to any woman who has ever had to justify her professional expertise to a man.

But she also noticed that the men she would shoot were very uncomfortable when she was taking portraits of them—there is a lot of observation and staring involved in portraiture to make sure the lighting, framing, and posture are correct, and many of the men she worked with seemed uncomfortable with her observing them that closely. Though she is still figuring out concepts and details, her next project will explore these male/female objectification dynamics through photography.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I have a couple of friends I collaborate with sometimes. We have a collective called Gulch—we’re four really good friends doing very different work and this was the simplest way for us to find more ways to hang out and also get paid. For me, it’s hard to collaborate because I’m so controlling. I’ve learned to let go a bit and ask for help and input, and I also learn about my own work as I’m asking for input because people bring their own aesthetics and style into it.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I start most of my projects when I’m having conversations with people. Language is really something I enjoy. People will say really interesting things and I don’t think they’re really listening to what they’re saying or even taking the time to think about what they’re saying. Most of the text I use are things I’ve heard people say or things I’ve found written somewhere. It’s an unplanned collaboration that wasn’t intended after having conversations with people that inspire the piece.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

These are conversations I always have with my friends: how we value our work as women, how we value our time, how we ask for what we think we deserve. My work has a lot to do with that. I’m trying to have those some conversations in my work around those questions that I ask people and ask myself. I’m Here is about how you talk about your value as a woman. Like on reality TV shows, the woman always has to say she’s not there to make friends and she’s not trying to be nice. If she shows up telling people that’s who she is then she saves herself from [the criticism that she isn’t friendly or nice or welcoming, which is what we expect women to be]. Those questions are present in my work and I want to have more of those conversations through my work.

(4) How do you define success?

I think if I have at least one person who is excited about the work and wants to engage with it I would view that as much of a success as selling the work. I definitely don’t sell everything and it’s nice to, but it doesn’t feel as fulfilling as when someone comes up to you and says, ‘Wow, that really inspired me,’ because I know what that feels like to see something and want to know more about it or be inspired by it. There are so many conversations happening in the world around you, so success is being able to be part of someone’s conversation.

(5) How do you fund your work?

With my paycheck. Lately I’ve sold a few pieces but I’ve definitely made a lot of work where I feel like the money just goes into a bottomless pit. I had a show in 2013 that I spent a lot of money on and didn’t sell a single piece, and that was really discouraging.

I totally get the starving artist stereotype, but it’s not because you’re starving but because you’re spending all your extra money on your work. The goal is to make some of the money back so you can keep making more work and that has worked for me so far.