Jamie Horter is a rural artist working in community engagement—in her own words

This article is part of a series highlighting artists and leaders featured at the Rural Arts and Culture Summit, a biennial, practitioner-driven gathering hosted by Springboard for the Arts that celebrates and expands the field of rural arts-based community development. The 2019 Summit will take place October 3 – 5, 2019 at the Reif Center for Performing Arts in Grand Rapids, Minnesota. Learn more and register at www.ruralartsandculturesummit.

Jamie Horter lives in Lyons, Nebraska, a town of 850 people according to the 2010 census, though the most current population estimates have reduced it to 805. She grew up in neighboring South Dakota in Bristol, a small community that had a population of about 450 while she was growing up (it has since shrunk to about 315).

“I moved to the big city, now!” Horter jokes about her proclivity for the smallest of small towns.

She hasn’t always lived in such rural communities, though: The artist lived in Washington, D.C. for a “short stint,” but simply found it was not for her.

“I wanted to be back in a rural place and I found a way back to rural living through a job opportunity, so I took that ticket,” she says. “There is so much about rural living that I love and I know it’s for me.”

When asked what she loves about it, she names the landscape first and foremost. She believes that people who live in rural places have a connection to the land and that resonates with her; the land is especially important to her because she grew up in the prairie.

“When I was living in D.C. I found myself thinking, ‘I need to get back to a rural place because I need a clean horizon line,'” she half-jokes. “I love the landscape, and having that vantage of going out at night and being able to see the stars is an amazing aspect of rural life. It’s quiet. It provides a lot of space for thinking, and that for me as an artist is really important. I think that there are good things that come out of that solitude, and being able to free your mind for a while. You can do better work that way.”

Horter also loves the people in rural communities, which is why she is a rural artist working in community engagement.

“That is something I’ve always been involved in and the thing I have been most driven to do,” she says. “I think the work I’ve done in the past that has been the most meaningful to me has always been around art that involves community collaboration, engagement, and empowering people.”

Horter describes her work as “multidisciplinary,” and she means that as much philosophically as she does more literally—yes, she has worked on many projects in which the output ranged from the visual to the literary to the more purely participatory, but it is the participation itself, and all of the conversation and community engagement that it entails, that she really considers to be the work.

“I’m always thinking from different perspectives and learning from those different perspectives, [considering] what might be the best thing to incorporate in that practice at that time,” she says. “For me, the work is an ongoing practice and I learn from it as I go, and it’s not isolated, either: I’m with community and I learn from community. It’s an ongoing conversation.”

She has been doing this kind of work for as long as she can remember, going back to her childhood when she did some forms of community engagement work without even having a name for it or thinking of it in that sense. Today she is a working artist making a living off of this work, though she still also does volunteer work, too.

“It’s work that I’m drawn to do and it’s integral to who I am, so I have to keep doing it. Either way, [whether the project is funded or I’m volunteering my time], it’s still very important work.”

Horter earned a bachelor’s degree in art (and also chemistry) from Augustana University in Sioux Falls, though she chose not to pursue an MFA because she preferred to delve right into her work immediately. She prefers to specifically describe herself as “a rural artist working in community engagement” because she feels that that resonates with people in a way that using any particular language from the high-art world would not. Some people may see the work that she does as “art” and some may not, and to her that’s fine either way; the language around the work doesn’t ultimately matter. But the way she approaches the work is always through the lens of an artist.

Sculpture is a big part of her background and that does manifest in some of her projects, but her work often appears more in the shape of a process rather than a tangible end product—a “social sculpture,” if you will.

“Dialogue is the main medium for the work I’m doing,” she says. “It’s really important in community work to have good conversation, as well as listening, in order to design the projects so that ultimately the projects are informed by the community and what’s happening in that conversation. In some cases that conversation might be the work. It often is the work.”

Horter views her art practice and community development work as one and the same. The medium might change with the project, but the heart of the work is about building local capacity in rural communities.

“It’s around empowering people to build community, and I think also an important aspect is that validation comes from the local community; it’s not coming from the high-art world or from outside communities or urban areas,” she explains. “Part of the work is about reframing the rural narrative and giving the people the chance to tell their own stories and to decide what’s important work to them. In that way the work is iterative; it’s constantly being reshaped from the context of practice and community.”

Working in community engagement and community coaching, Horter has a few different ongoing projects in the rural communities of Lyons and neighboring Decatur. Her main ongoing project is called Community Studio, which started five years ago in collaboration with the Lyons-Decatur Northeast school district. Horter had a conversation with then-principal Derek Lahm about bringing students out of their textbooks and into the community more.

With that in mind, they designed a program through the high school civics class for seniors that would enable them to have a platform to create an independent project of their choice, as long as it benefited the Lyons or Decatur communities in some way. Students have designed a variety of different projects, from processes to tangible built environment pieces. One student started a literary night at the local library in Lyons, when people were encouraged to bring in whatever they were reading—this ranged from the Farmers’ Almanac to a scientific journal—and a local poet would read some poetry that he created. This was an ongoing event open to anyone and everyone.

More recently, some students worked on designing a Frisbee golf course for a local park; they just finished pouring the concrete and setting up the course, so it’s now ready to use.

“It’s really up to the students to decide what it is they’d like to create, but we help provide the time, space, and some support for them to work through those projects and do something that maybe they’ve never tried to do before in their lives,” Horter says. “Part of this project is about showing students that they have the capacity and also the power to do good work in their communities, and this provides them the opportunity to do that.”

One of the goals of Community Studio is to let these students know that if they leave after they graduate, whatever it is they decide to do or wherever they decide to go, they have the capacity to practice their citizenry in whatever community they’re in. In addition to that, they also want the students to know that their skills and talents are always wanted in the communities of Lyons and Decatur, and they are always welcome back in these communities.

Many of Horter’s projects focus on youth, and that’s because she feels that youth are often marginalized within communities, and not just rural ones.

“They don’t have full rights; they can’t vote yet. They aren’t necessarily recognized as citizens with the capacity to do good things,” she says. “I think this program works to counter that narrative, which helps adults see the ways in which youth do have the capacity to great things, and it also helps youth to see that there are adults who are supportive of youth trying something new and experimenting.”

With Community Studio, Horter and her collaborators are very purposeful in letting the students know that it’s okay to fail, and that the whole point of the project is not to create some successful end product.

“This is about the process of learning how to move through a project. Sometimes projects don’t work out and that ‘s life, but the important thing is that you learn from them.”

Oftentimes youth aren’t given a voice to express themselves in communities, she adds, so this partnership with the school district provides them that opportunity.

In addition to working frequently with youth, Horter’s work is also intergenerational. A second project called Senior Spotlight grew out of Community Studio about four years ago, and this project pairs seniors with seniors—high school seniors with senior citizens, that is.

“Senior Spotlight brings together two generations that are often in the periphery of society, which are youth and senior citizens,” explains Horter. Over the course of four weeks in the fall, each participating high school senior spends time with a senior citizen in the community, interviewing them about their life and also learning portraiture in order to create a portrait of that person. They also develop fundraising skills by raising money for professional prints of the narratives they write and the portraits they create.

Then, in collaboration with the downtown Lyons building owners, those works are installed in storefront windows, all culminating in a public reception that the senior students host along with the senior citizens. The public is invited to take a walk down Main Street, look at these portraits and narratives, and engage in conversation with both groups of seniors.

In the winter the project is displayed in the Decatur Sears Center, a senior center that is also an art gallery, so both communities have the chance to display and celebrate the works created through this project. Horter has also led Senior Spotlight as an Epicenter Frontier Fellow in Green River, Utah.

She feels the project is important because it helps to render a spotlight on youth and senior citizens: two groups of people who sometimes are not “seen” in the community. It demonstrates that youth have great capacity to do great things in the community if they’re given the opportunity, and that there are still ongoing contributions that senior citizens are making in the community that are important to highlight.

Currently she is busy working on a book that gathers together all of the portraits and narratives created through Senior Spotlight and publishes them as a way of archiving and preserving the community’s rich cultural history, especially since some of the folks who have previously been involved in the project have since passed.

“We’re really grateful that their stories will be retained in the community as members of the community,” says Horter.

Horter also does a lot of work in South Dakota through Dakota Resources, which includes community coaching in rural places to help with economic and community development—building capacity within people in rural communities to help them build the future together and co-create the rural that they want.

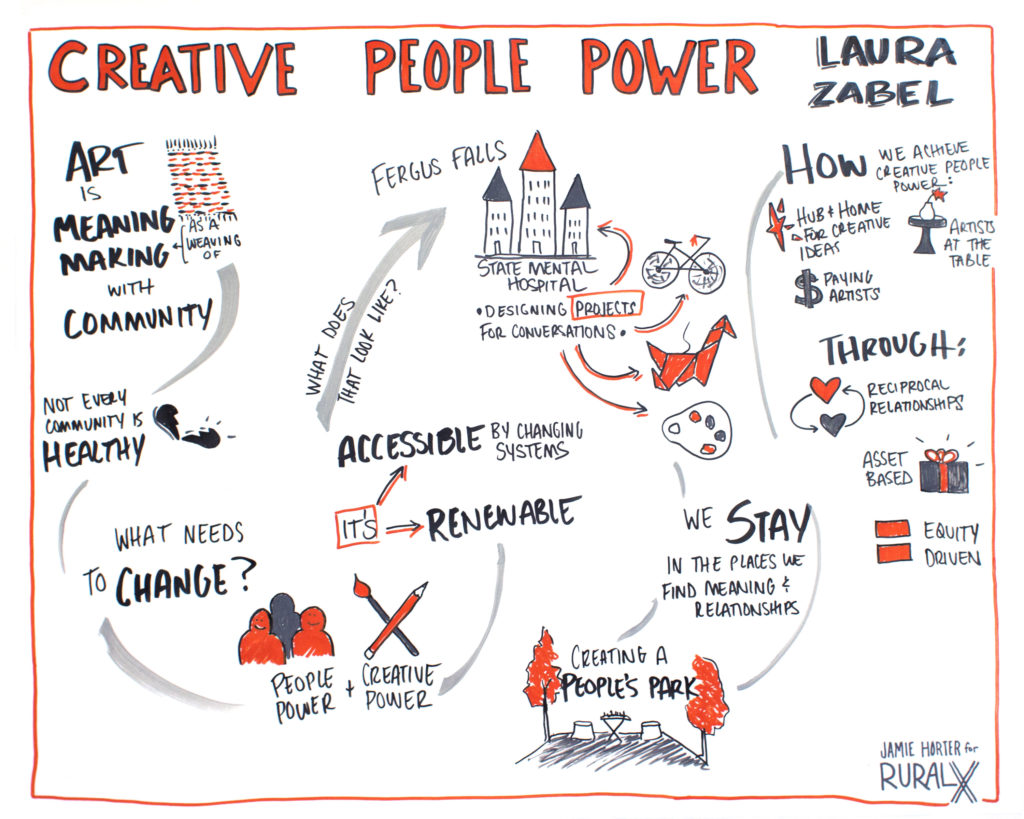

She additionally does graphic facilitation and graphic recording, which she describes as “just another way to help people make meaning together.” It is essentially a visual representation of a conversation or speaker presentation to help the visual learners in the room. “I turn words into visuals that people can remember; it’s just another form of collective meaning-making.” She recently made a graphic recording of the talk Springboard’s own Laura Zabel gave at the 2019 RuralX convening hosted by Dakota Resources.

Horter is very mindful about the projects she takes on and where they are located. Time is one of the most important factors in community work, and while her instinct is to always want to say “yes” to every project, she also wants to do good work in the places she’s invited to, and never wants to be the artist who drops in, does whatever project she wants, and leaves.

“Good community work takes time, so it’s really important to invest in a place and its people,” she says. “Sometimes it’s hard to get to know a community in a short trip or a very short residency, so I really am intentional about the projects that I take on because I want to be able to invest the time in the community to make it work.”

She’s also passionate about highlighting and supporting the local artists in other communities and giving them the opportunity to do this kind of work, rather than bringing someone else in from outside the community.

“Another question to be asking those communities is, ‘Who are the artists in your community who could be doing this work?’ One thing I’ve learned through the years is that there are many artists in every rural community. You might not know about them, but they are present and they are creating in their own way and on their own time. They might not even call themselves artists, but there are people who are creating and who have artistic skills who might be perfect for what you’re looking for. But it might mean that you need to get out a little bit more in your community and start asking more questions.”

She sees a lot of that when she’s out in the field—people who are “artists” by anyone’s definition but who resist defining themselves that way.

“I tell people that everyone is an artist, and that the ability to create is one of the traits that makes us uniquely human. However, when we grow up within systems and institutions that devalue creative expression, then this trait becomes an unused muscle. We start to internalize what we’ve heard; so maybe someone has said, ‘You’re not an artist,’ or ‘You’re doing it wrong,’ and eventually we stop creating, or we stop creating because the system doesn’t sufficiently economically support that creative work. And when that happens our communities suffer, because collective self-expression is the very way in which we build culture. It’s what weaves our social fabric; it’s what shapes the identity of our shared spaces. Every community needs its citizens to embrace their creative power.”

Why? She further explains: “Because we can use art to fight back against the narratives and those actions that disempower us, and we can use self-expression to be a mechanism for resiliency against oppression. I think that, specifically, one of the roles of an artist is to remind people of their own power to create and to uplift their voice in the public realm, and I think another role of artists is to help provide public platforms for more voices to be heard and represented in the public discourse.”

Through all of her work, Horter wants people to understand that people in rural places matter, and that’s often left out of the narrative.

“I think this work is really around helping retain our shared humanity, to help people recognize their capacity to make a difference in their community, and to work towards collective creation rather than destruction, rather than marginalization, and it starts with reframing that narrative on a personal level.”

Additionally, art is just as crucial as economic development to build strong local economies and strong rural communities. Art is often left out of that conversation, she says, with the emphasis typically being entirely on economic development. But it’s equally important to use art to safeguard and create new characteristics of that rural place that don’t have a price tag—the “poetics of place,” the things that form identity and a sense of belonging, those unique qualities that touch people’s hearts and render what “home” means.

“The shapes of the natural landscape, the relationships and sense of community, the stories we tell ourselves, how we work together as a community, how we create culture together, how we express ourselves as a community: Those things are all deeply impactful to the health and well-being of rural communities, and they are separate from economics, but they’re often devalued or extracted by our current economic system. Art is really important here because art provides space to uphold, preserve, and build upon these types of assets that we have in rural communities.”

When we think about the thriving rural communities of the future, she says, they will need both bold new economic systems as well as vibrant art and cultural production in order to shift the status quo, and it is crucial that artists and cultural producers be at the helm of that design work alongside economic development professionals and community leaders, and not left out of the conversation.

How do you like to collaborate?

I love to collaborate with rural people. And some of the best collaborations have been with people who have skill sets different from my own, and people who don’t identify as artists. Our combined skills make a process better together.

Relationships and shared values are important to me in collaborations. Some questions I consider are: Do we care deeply about this rural place and its people? Do we recognize that this work is about community, not us? Are we willing to trust the process and keep a steady focus on the larger vision? Do we trust each other? Will the work be stronger with our collaboration? Is now the right time? There’s a running list I keep of people I’d like to collaborate with based on those sorts of things. Get in touch if you think you should be on that list. 🙂

How do you start a project?

It could be through invitation or happen organically through dialogue. It’s an emergent process and the project reveals itself over time.

An invitation might be an ask to bring one of my past projects to a community. At that point, there’s a lot of dialogue to explore whether it might be a good fit for that place. Every community is different, so it’s important to have shared values and expectations around a project and make sure it’s something that’s right for them—and me.

When it happens organically, the project emerges over time through the relationships and connections formed in communities. Conversations lead to ideas that set the groundwork for collaborative work in community.

How do you talk about your value?

I do work that I get excited about, that I believe in. When I talk about the work to others, that passion comes through because I genuinely mean it. I tell stories about the impacts of the work; I paint a picture that helps people see possibilities.

How do you define success?

Waking up each day able to spend my time being an artist. That is everything to me.

How do you fund your work?

Historically that’s meant working a side gig that was unrelated to the work. Art would be the thing I would get to when everything else was done. That was painful.

Not every project I do now is directly funded, but my time now is spent doing the work I love. That is something I never take for granted. It’s a mix of contract work, public and private grants, and donations that support what I do.

I wish more art programs would incorporate courses on fundraising and entrepreneurship. I’ve learned some of those things through training, trial and error, and having great mentors. I’m still learning how to be better at them so I can continue to support the work.

Ultimately I believe we should work toward a system where artists are fully compensated for their vital cultural, problem-solving, visionary work.

All photos by Jamie Horter except where otherwise noted. Lead image from the prairie sculpture project done in partnership with Prairie Plains Resource Institute.

Yes! Me too. I’m a rural creative collaborative artist. I’m a 2nd grade teacher and yoga instructor as well. I combine these skill-sets to develop, offer and co-host artistic events. My team and I hold space for people to connect, make art and lasting relationships statewide in South Dakota. My focus project is Linking Fences, where large scale public art installations are done on chained link fences in multiple communities with diverse groups. I live for it and love what you’re doing too!! Yes, yes yes!

Loving what I’m reading. Thanks ~ I wanna be like you.