From Trenton, New Jersey to rural Vermont, Will “Kasso” Condry uses art as a catalyst for activism and revitalization

Will “Kasso” Condry, Jr. is a pioneer of the street art movement in New Jersey, and made national headlines in 2014 when he painted a mural of Michael Brown, the Ferguson teenager who was shot and killed by police despite being unarmed and whose murder sparked several weeks of widely publicized protests. The mural, which included the words “Sagging pants is not probable cause,” was covered up by the City of Trenton, but Condry’s message had already been heard.

Condry grew up in Trenton, New Jersey, a blue-collar, former industrial town that had fallen on hard times starting in the 1960s with the nationwide race riots. Growing up in the 1980s and ’90s, he said, Trenton could be “a very dark place.”

“I grew up in the middle of the crack era,” he says, “There weren’t too many opportunities promoted to youth in Trenton at the time that weren’t just, ‘Get out of Trenton.'”

But Condry stayed in Trenton, and nurtured the passion he had for art that he discovered at a very young age after taking free art classes at Artworks Trenton. He went on to study fine art and illustration in college, and after college he delved into street art, painting vivid public murals in aerosol. He was instrumental in ushering in the Trenton art scene, earning the nickname “Godfather” for his work in procuring economic support for artists and also for getting people from the inner city involved in art practices.

“I realized that if I didn’t have that outlet [of art], things might have looked a lot different for me,” he says. “Being an artist allowed me to be whoever I wanted to be.”

He co-founded the Vicious Styles Crew, the first organized graffiti art production crew in Trenton. Condry is also the founder of the S.A.G.E. (Styles Advancing Graffiti’s Evolution) Coalition, a nonprofit organization of visual artists, engineers, fabricators, musicians, makers, and teachers dedicated to developing inner city beautification projects. Condry has produced dozens of murals throughout Trenton, the Northeast, West Coast, and internationally.

Civic Engagement: Community Muralist ~ Will “Kasso” Condry from Lori H. Ersolmaz on Vimeo.

The main focus of the S.A.G.E. Coalition, which formed in 2012, was “to bring arts and culture to the communities that needed it the most,” says Condry. He wanted to remind those in economically depressed neighborhoods that unity and pride could thrive through creative problem solving and civic engagement.

Through the S.A.G.E. Coalition, Condry was able to get involved in a wide variety of different projects: Among other things, he worked as the manager and curator of Trenton’s Gallery 219; hosted the annual “Windows of Soul” event, a three-day-long block party and neighborhood beautification project; and created the community “Gandhi Garden,” which prominently featured a mural of the world-famous social and political activist. The garden even attracted the attention of Gandhi’s own grandson, who showed up one day unannounced to see it for himself.

Meeting Gandhi’s grandson, Condry says, was “the jolt we needed to know the work we were doing was headed in the right direction.” S.A.G.E. used arts as a catalyst for urban revitalization; not in a gentrifying way, but in a way that encouraged people in the neighborhood to take pride in where they live and protect it, as well as spark important dialogue within the community—such as the intention with the Michael Brown mural.

However, by 2016, the work had become difficult to sustain.

“Things started to get shaky,” he says. “We were running a grassroots nonprofit in a city with a limited tax base, and we were holding it together by shoe strings. I realized my time there was coming to an end, really because of limited support and lack of resources. I decided it was time for me to leave and get out into the world.”

So Condry moved to Middlebury, Vermont…a pretty drastic switch, but not without precedent.

In 2012, Condry’s niece convinced him to come to her school, Middlebury College, to give a talk on using art as a form of activism. While he was there, he met Jennifer Herrera, associate director of the Anderson Freeman Resource Center (AFC) at Middlebury College—and his future wife. The two kept in touch for several years and when Condry decided it was time to leave Trenton, she invited him to Vermont as the Alexander Twilight Artist-in-Residence at Middlebury College. And from there, the two grew closer and closer.

“In 2016 we picked up where we left off,” he says. “As soon as I came here [to Middlebury], I had an overwhelming sense of feeling like I was at home. This was a place I never expected to be, but things started opening up to me here.”

During his residency he created several murals at the AFC, the school’s multicultural center, and also led workshops, met with students, and otherwise continued his practice of using mural arts as a vehicle for activism and beautification.

“I wanted to do grassroots community organizing around the arts, which you can do everywhere because art is universal,” he says. Since then he has painted murals at several other universities, middle schools, and elementary schools around Vermont, and has also taught a course called “The Origins and Politics of Graffiti and Street Art” at Middlebury.

“That was definitely something I never thought I would be able to do in a school like Middlebury, but the students advocated for it,” he says. “Things have definitely opened up for me here. Graffiti and street art are global, but in the context of rural America it’s still a head scratcher—[people wonder] why you would bring this urban artwork to a rural economy.”

During his last three years in Vermont, Condry has also been an artist-in-residence at the Clemmons Family Farm, one of only 19 Black-owned farms in the state of Vermont (which has over 7,000 farms). The Clemmons Family Farm hosts African heritage arts and culture programs, including residencies, to improve community wellness and address the social isolation often felt in rural communities, particularly by people of color.

“I used that platform to document the Black experience in Vermont,” he says. “I talked to other Black Vermonters to see how they look at this place. I was still very fresh to it, and I’m still learning to this day, but this showed me that there are people of color in this state and that needs to be highlighted, and what better way to galvanize people than through art because it’s universal.”

Earlier this year Condry attended the Rural Generation Summit in Mississippi as part of his work with the farm, and his eyes opened to the level of interest and the endless possibilities in rural communities.

“They took us on these tours and I just kept seeing giant slabs of blank canvas. I saw that there’s so much that can be done, and not just by bringing artists [from outside the community] in. I think that’s a mistake a lot of organizations make. There should be just as much interest in cultivating local talent to show them that everything you could want to achieve, you can do through art.”

He really wants to push for more public art in Vermont because of the ways in which public art can support and grow a local economy.

“Regardless of whether you like it or not, public art brings people in,” he says. “People come into the towns to see it and they spend money in those towns.”

It’s important to encourage these kinds of economic drivers, he says, because poverty in rural areas isn’t as visibly obvious as in urban areas, but it is still very much there.

“Just because you don’t see boarded-up houses doesn’t mean they’re not living check to check,” he says.

While Condry is still figuring out how his work fits into a very rural environment—all the more so now, since he and his wife purchased a house in Brandon, Vermont, a town of just 4,000 people (less than half of Middlebury’s population of around 8,500)—he also says that there is a strong community of artists in Vermont, as well as folks who have spent their entire careers in social justice work. He says he wouldn’t be anywhere that he’s not appreciated, and his work is appreciated here.

“Vermont is a very progressive, very liberal state,” he says. “Artists need other artists to feel alive, and there is a community here. You never know who you’ll meet out here; I meet so many influential people and they came out here just so they can be ‘regular.’ That helped make things more palatable to me. As an artist, you still need people around you who think like you and want to do things like you.”

He also views it as unchartered territory, a place to create murals where murals don’t yet exist and also a place to focus on honing his studio practice when there aren’t any walls to paint.

“My goal is to spread my practice as far as I can. I have the mentality that I just have to keep making art,” says Condry. “At the end of the day I still have just as much fun as I did when I was kid, and I appreciate that because things could have gone a lot different from me otherwise.”

The slower pace of life has also slowed down his practice, but in a way he welcomed…eventually.

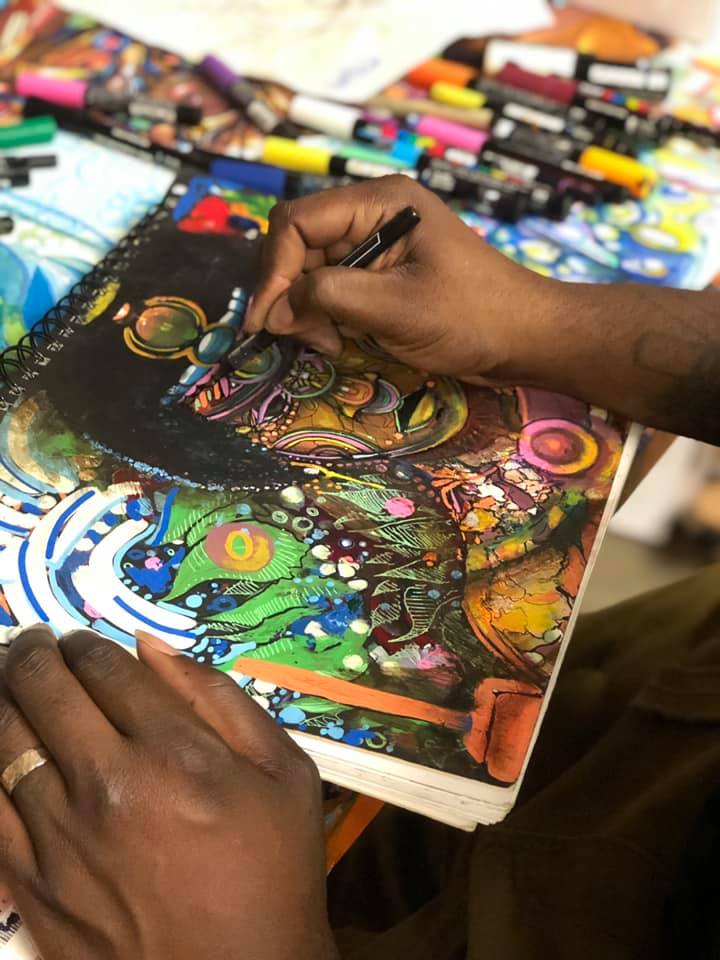

“When I first moved here I was working on very small canvases and I was pulling my hair out because it was taking forever and my patience was being tested,” he laughs. “My work is more refined now. Prior to Vermont, most of my work was done in spray paint. Being a muralist allows you to work very fast and large, but now my style has evolved because I’m taking time with my work and it has become richer and more vibrant.”

“A snail’s pace is still a pace,” he jokes, “just don’t stop. Don’t quit. No matter how slow it’s going you still have to chip away it and live in your passion and your purpose. My passion is to make art and connect people, no matter where I am.”

He also says the tone of his work has changed a bit. “Coming up in graffiti, I became a legend where I was because of being politically oriented in a particular way. My work still has that tone, but it’s a little quieter now.”

Now Condry focuses on his studio practice, paints murals when and where he can—which includes his garage door, making theirs the most popular house in town—teaches part-time at the college, and diversifies his practice in whatever other ways he can.

“To be successful you have to stay consistent. You have to keep moving forward,” he says. “There’s a list of times I should have quit because of what someone said or did to me, but I just went back and [kept creating]. You have to diversify and find your way. The last 15 years of my life have been spent using my art to help rebuild areas that have suffered from political agendas; now the area I live in is so spread out, but the creative opportunities are limitless. Now I feel like, ‘Where do I start?'”

Currently, Condry and Jennifer are fixing up their house, which sits on a half-acre lot in Brandon, so that they can host artists in the future. The calm, peaceful setting makes for an idyllic artist’s retreat—a sanctuary of self-care where artists can create and recharge. As for right now, Condry is focused on enjoying himself in his newfound home.

“The thing about rural living is that everybody knows everybody, so everybody looks out for each other,” he says. “You don’t get that in urban environments. I live in a community where people are just cool and appreciate you being there. Having people around you who generally care about and love you—that’s priceless. I’ve been here almost three years and I’m looking forward to what’s next, even if it’s three feet of snow.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I like to collaborate with people who are open to getting outside of their comfort zone.

(2) How do you a start a project?

By praying.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

Typically when I’m talking about value I use examples of different things I’ve done. I just talk about my work and experiences of my work, good, bad, or indifferent, and let people listen and let the story speak for itself. I typically don’t talk about monetary value, but it’s more or less implied. I tell people no matter what world you operate in, nonprofit or otherwise, generosity requires funding.

(4) How do you define success?

Success really comes in the feeling. That’s how I know when the project is done: it’s the feeling you get from the people around you who are affected by what you just did. I tell people once I’m done, it no longer belongs to me, it belongs to the community. If they don’t value it and take care of it, it won’t last long. The success comes in the people you’re helping; the art is just the fun part!

(5) How do you fund your work?

I watched this Orson Welles documentary on Netflix and it talked about this one film he was self-financing and how he had to act in another film to get this other one done and it took two and half years. I just kept laughing at that because that’s how it is! You HAVE to diversify. Yes, there are grants and other sources. Yes, I love public murals but I have a finite amount of space for them, so I also design beer labels. I design tattoos, and I’m about to start my tattoo apprenticeship. For me, it’s about being as diverse as possible in my practice so I don’t get pigeonholed as one thing.

For me, being a working artist for about 17 years now there has been a ton of peaks and valleys. I’ve learned that I have to focus on this right now because it pays the bills, and then come back to work on the project that I don’t have the money for right now. I’ve definitely found a way that just challenges myself all the time. I constantly walk into unfamiliar territory to the point that I’m no longer afraid of the dark. I tell young people in college, “If you have a business idea, start building it right now.” You HAVE to diversify your portfolio. You have to be very careful of how much you put into one thing. It’s that saying, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

For me right now, teaching full-time isn’t an option because to be a successful teacher you really have to dedicate yourself to it full-time, and that takes time away from my art. Last year when I was teaching full-time I didn’t have much time to finish my pieces, so now I’m focused on that. I still teach, but I teach part-time. I love sharing my wisdom and teaching kids; I can’t take that knowledge with me once I’m called.