What would happen if the NEA were defunded, and why should we care?

It has been a little over six months since Donald Trump took office, and a lot has happened during that time. Although the budgeting process for the federal government is a long and arduous process which has only just begun, the Trump administration’s initial budget proposal raises important questions that are relevant to address. In particular for organizations and individuals working in the arts and at the intersection of art and community development, “What would happen if the National Endowment for the Arts were defunded?”

The question of why the NEA matters is a big one. You can argue that the nation that brought the world blues and jazz, pioneered dance forms and art movements, is the home of the international film industry, should have representation on the federal level of our cultural heritage. You can point to the creative power of artists to shape their communities, and share the stories about why their place matters – Creative Exchange is full of those stories. You can make the case that art and creativity is fundamentally and intrinsically important, and worth supporting. It’s one thing to feel that way deep within your own soul; it’s quite another to make an articulate case for it to someone else who, quite simply, doesn’t see it the same way.

In the case-making that does reach beyond believers in the arts as an intrinsic good, look to the power of the arts as an economic driver and job creator, talent attractor and holder of a community’s identity. One of the Trump campaign’s greatest rallying points for his constituency, largely comprised of poor white men without a college education who live in areas of racial resentment (especially prominent in the rural South, Great Plains, and Rust Belt) and feel they have no voice, was the promise of jobs. The white working class and middle class voters that propelled him to victory liked the fact that he was a political outsider and an ostensibly successful businessman, and he was able to capitalize on their economic anxieties and promise to bring back jobs that were lost not just to outsourcing, but to the creative destruction that comes when whole industries are displaced by evolving technologies.

Jobs: the argument going something like, “We don’t need paintings; we need JOBS,” as if it were a zero-sum game; as if having one meant not having the other.

In an appearance on Morning Joe, as quoted in The Week, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said, “When you start looking at places that we reduce spending, one of the questions we asked was can we really continue to ask a coal miner in West Virginia or a single mom in Detroit to pay for these programs? The answer was no. We can ask them to pay for defense, and we will, but we can’t ask them to continue to pay for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.”

“Everyone, including those in the legislature, loves the arts, but when it comes around to public funding, the story changes,” says Robert Booker, retiring Executive Director of the Arizona Commission on the Arts. “They have no concept of access for other folks, or they think that we have so many things on our plates and there’s so many other needs, so every year the legislature has a new theme – one year it’s ‘babies on oxygen,’ the next it’s ‘seniors in diapers,’ then it’s ‘diabetes. The argument that ‘we have to cut this to do this’ is ridiculous; we can do both. We want bread AND roses. We have to challenge them: ‘We’re asking for $2 million of our of $2 billion budget; how are we hurting babies?’ We have to teach our advocates to push back and say, ‘I don’t buy this. I don’t buy this bait-and-switch.”

Though Booker speaks specifically to state level funding in Arizona, the conversation at the federal level is no different in its tendency towards themes, and right now the theme of the federal conversation is all about jobs. So it is not without some dark irony that the NEA became one of 80 federal agencies and programs targeted by the Trump administration for severe funding cuts or elimination, including also the EPA, the Department of Agriculture, NASA, that largely benefit rural and low-income Americans, his voters.

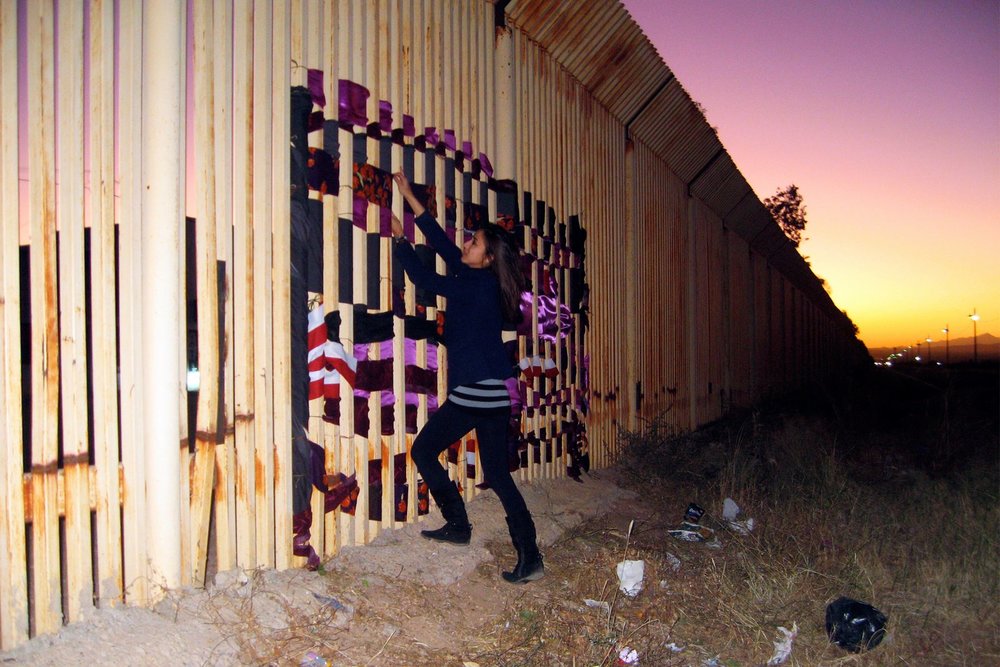

Springboard for the Arts addressed this head-on in a statement released in the immediate aftermath of the budget proposal (that has, thankfully, thus far gone nowhere, much like every other attempt at ramming through policy changes Americans don’t actually want). Springboard’s Executive Director Laura Zabel also spoke with the Christian Science Monitor about the proposed cuts, pointing out that the impact on a rural town like Fergus Falls, Minnesota, where 64 percent of voters chose Trump in the presidential election, would be felt far more than by the “liberal elites” that conservative commentators have claimed solely benefit from NEA-funded programming.

In a follow-up conversation with Creative Exchange, Zabel also addressed the issue of jobs.

“I find it super confusing that people don’t think there are jobs in the arts,” she says. “[The] Fergus Falls [“Our Town” grant] created three full-time positions that didn’t exist before, and in a small community that makes a difference. With people who work at arts organizations and in the arts, it’s not just those jobs but they have multiplier affect because they make small communities places where people want to live. Figuring out how to build the next economy for their region or town utilizing culturally relevant opportunities to share their culture and identity with each other will be the competitive leads for those communities. Those that don’t will be left behind in terms of very real economic impact.”

In an era of alternative facts, it is increasingly difficult to use quantifiable data to support a point, but here goes: according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 2014 (the latest year for which data is available), 4.8 million people were employed in the arts and cultural industries. Supporting arts and cultural production industries accounted for 3.58 million of those jobs. In total, arts and cultural economic activity accounted for $729.6 billion, or 4.2 percent of the Gross Domestic Product….more than construction ($619 billion) or utilities ($270 billion). This reflects a growth in GDP contribution of more than 35 percent since 1998. Total spending on all arts and cultural goods and services reached $1.1 trillion (adjusted for inflation). And all of this was accomplished – by federally-funded arts and cultural programs including the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and others collectively – with a scant 0.0625% of the estimated $4 trillion budget.

The arts aren’t just for liberal elites who enjoy the occasional evening at the opera. The arts have a real economic impact in America, in both job creation and GDP contribution.

Even if the NEA were completely eradicated, that economic impact would continue, although in a diminished way. Zabel sees the NEA as driving resources to creative placemaking, economic, and community development initiatives in smaller communities and for smaller organizations that wouldn’t otherwise have access to national thought leadership. As a sort of seed investor, the NEA tends to shine a spotlight on such organizations, putting them on the radar of larger funders and attracting larger dollar amounts. That, she says, was a major factor in the growth of Springboard’s Fergus Falls office, and now the work they do there is sustainable.

“Without that early investment [from the NEA] we would have had a hard time attracting that other private investment. [Without the NEA], it would be much harder for new work and new organizations to begin.”

Major arts programs and organizations across the country would experience some adjustment pains but would continue on. It would be the rural organizations and programs that would be decimated, and that should be a serious concern.

“The whole budget proposal disproportionately targets rural communities and economic development agencies in those communities,” Zabel says.

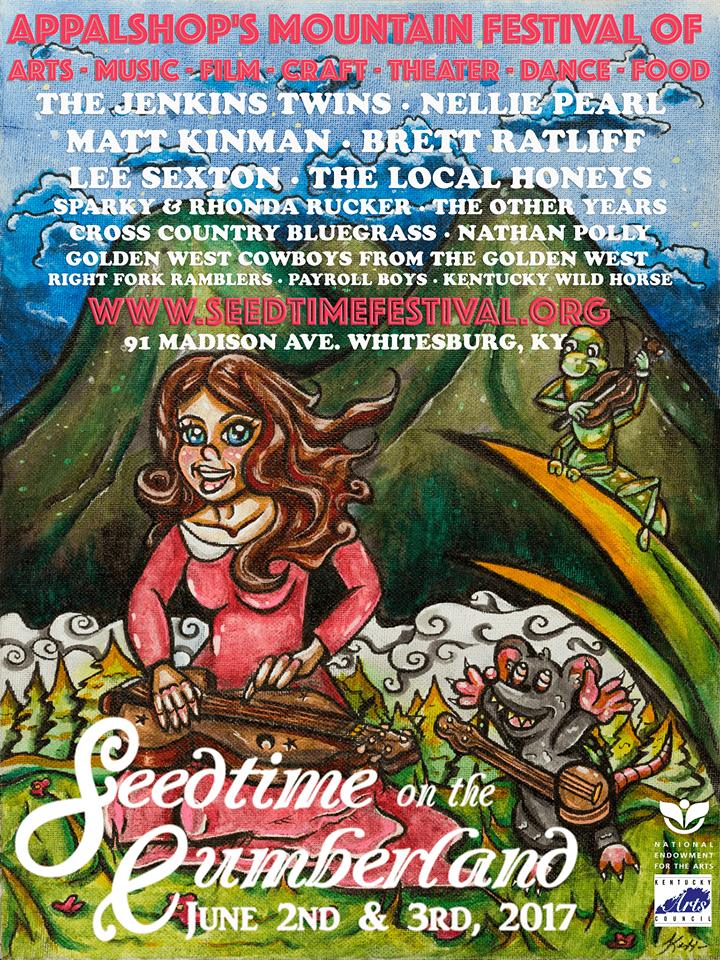

At Appalshop, an organization located in Whitesburg, Kentucky that celebrates the culture and voices the concerns of people living in Appalachia and rural America through cultural organization, creative placemaking, media production (including documentary film and radio programs), and arts and culture education, about 30 percent of their funding on any given year comes from federal programs on the proposed chopping block. About five to ten percent of their annual funding specifically comes from the NEA.

Alexander Gibson, Executive Director of Appalshop, says, “If a worst-case scenario budget passed, it would affect us to a tremendous degree in the 30 percent range. If it were only the NEA [funding that was lost], it would still be catastrophic.”

As he explains, the NEA supports the organization’s operational capacity in ways that other donors don’t.

“Funders have a stereotypical proclivity towards supporting a project but not the means of doing so,” he says, referring to basic operational needs like infrastructure and administration. “The NEA tries to fund in a different way, channeling into means and methods, where other funders fund outcomes.”

Gibson also points out that it’s not as if everything is all rainbows and puppies with the funding as it stands currently.

“Things are tough already. Even if things stay intact, it doesn’t feel like a win. Everybody here is underpaid. Working here just as tough as corporate law [his previous career]. I want to give everybody so much more money for the work we do and we just don’t have it. People talk about cutting more – I would lose a lot of staff people who have been hanging on in the hopes that things can get better.”

He says they also can’t pass the difference off to customers and they don’t have corporate sponsors to make it up or private donors with $30 million to hand over.

“When you set up in a poor area to tell stories about poor people you don’t have a lot of rich allies,” he states. “We’ve been here since 1969. We have won Emmys. We have been to the White House. We have won the MacArthur Genius Award. We have produced over 100 documentaries, countless albums, and a 24-hour radio broadcast, yet we have no wealthy friends. But the Kennedy Center has a lot of them.”

Matthew Fluharty, Executive Director of Art of the Rural, echoes that defunding the NEA “would absolutely hurt small organizations and it would significantly disadvantage rural-based projects because they exist within a ecosystem of human support and funding that is drastically different than what we see in urban environments.”

He explains that the NEA is one of very few national funding sources that is equitably supporting rural work. “When you look at how arts and culture funding is dispersed and how inequitable it is, what we lose at the NEA is a fully equitable partner in all of our country’s arts and culture projects.”

Consider that anywhere from 72 to 95 percent of the country’s land area is classified as rural (depending on the source and the subtle differences in classification) with 14-21 percent of the population living within it, rural America only receives three to six percent of philanthropic funding of any kind.

“I believe that’s a $20 billion shortfall in terms of support that goes to rural America each year, and arts and culture is really small portion of that,” says Fluharty. “But that gap also is a gap that supports the ecosystems that would support [economic development and community sustainability].”

He says that the NEA should not only continue to be funded, but should be funded far more so. And in addition to that, “We need to rigorously interrogate how American philanthropy is funding projects outside of metropolitan areas” because rural America is “radically underfunded by American philanthropy.”

The Art of the Rural, in collaboration with the Rural Policy Research Institute, has launched an initiative called Next Generation that seeks to address why arts and cultural programs should be funded – the question behind the question of why the NEA should even exist – and especially in rural areas.

He points to their “Theory of Change,” which attempts to look ahead to future generations and the importance of maintaining the culture of these rural areas and retain their younger generations.

“[In the future] we will see rural communities disintegrating,” he explains. “The question of culture is important when you look more broadly out. [Rural areas] have an aging population and workforce. How do we keep our young people here and stimulate economic innovation? We are not going to attract the next generation of leaders, crucial to the future of these rural places, unless we create communities that are equitable and legitimately inclusive and create an actual practical working environment where there are opportunities for economic innovation and civic engagement. If we’re not engaging young people in these communities they’re going to leave and they’re not going to come back.”

Arts and culture are key to this kind of engagement.

“[Young people] are not going to come back, feel included, or feel like they have a seat at the table if there aren’t engaging cultural opportunities where they can make things and expand themselves. We know Millennials want that.”

Furthermore, he believes that the results of the 2016 presidential election can be at least partially attributed to American philanthropy’s lack of rural funding.

“American philanthropy is such a force for good – for research and bringing folks together – and we can see those effects in our urban centers. Had rural America been equitably funded we would have cultural institutions here, and when you have those you feel valued, you feel your experience matters. The absence of those [in part] created the animus that contributed to the election results.”

Fluharty says NEA’s “Our Town” program, which funded Springboard’s Fergus Falls office and related programs as well as Art of the Rural’s Next Generation initiative, has “absolutely transformed how we talk about the value and the range of connections that arts and culture work can inspire in a rural place.” The NEA also provides the thought leadership for people to create those institutions themselves.

The concern over arts and culture funding in rural America isn’t merely the hand-wringing of liberal art college-educated nonprofit leaders whose own jobs are tied to the arts, as opponents might claim. The concern is serious enough that the Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) felt the need to get involved.

Charles Fluharty, CEO of RUPRI (and Matthew Fluharty’s father), says, “Sustaining rural people in place is important to America for many reasons: [as a safeguard against] pandemics and terrorism, for our urban brothers and sisters recreation, [and safeguarding against] the destruction of natural resources. If there is no stewardship of natural resources they will not exist. We have not been able to convince the elites of this. There are no men and women in the governance of national foundations [that champion this cause]. That is the reason that a public policy institution that works mainly in public sector came to believe we need to get involved in the arts and culture sector.”

RUPRI became interested in non-GDP-contributing rural wealth creation and working on new ways to assess rural policy and practice metrics after developing the rural dimension of the Ford Foundation’s and Aspen Institute’s WealthWorks framework. Since then, RUPRI has championed the policy standpoint that non-GDP rural wealth is critical, but because rural regions have less capacity and less density they receive far less federal and philanthropic investment per capita in community and economic development, which Fluharty Sr. calls “an amazing inequity.”

“We need to assess our overall assets in a very different way, because the space that is rural includes the natural resource base of our region,” he says.

The only way to sustain these areas, he says, echoing his son’s statements and their respective organizations’ joint “Theory of Change,” is to invest in quality of life so that people choose to live in these areas. And arts and culture are a major component.

“The places that are doing quality of life development where cultural capital is key are going to be the places that survive,” he states. “If we do not build those places, Millennials will not return or move to rural areas and older and younger folks will not stay there. That’s just a given. You can do all the infrastructure investment but if you aren’t doing cultural investment you will not have a sustainable community.”

One thing the American public can take away from the 2016 election is that rural America is a collective voice that has historically been ignored, and listening to that voice isn’t just a matter of import for rural Americans and the politicians hoping to earn their favor. It is critically important for all of America, and for the future of America.

And ensuring that the NEA remains funded so it can continue to do the equitable work that it does in rural areas is only the beginning.

Wonderfully said.

[…] What would happen if the NEA were defunded, and why should we care? […]

[…] Because of this, Sol Collective isn’t dependent on grants and foundational support…and thus not at the mercy of the potential whims of federal arts funding. […]