Tony Gómez-Morales explores cultural identity through cowboys and wrestlers

Antonio “Tony” Gómez-Morales is American. He was born in Mexico where he lived until he was 14, then moved to Southern California, attended Wayne State University and the College for Creative Studies in Detroit, and now lives in Las Vegas. You can call him Mexican or Mexican-American, if you must, or Latino/Latinx if you prefer, but as far as he’s concerned, he is simply American.

But to many white Americans, he is Mexican and nothing else. And since young adulthood, he has struggled to reconcile these different identities—the boy who grew up in a small town in Mexico who idolized luchadores like the Blue Demon and genteel charro culture, and the SoCal teenager who listened to the Smiths and went full mod in order to assimilate into his new, predominantly white home.

Eventually that struggle for identity and yearning for lost heritage manifested in his artwork, and he created several series documenting what were essentially pieces of his own life and the culture he himself experienced and missed.

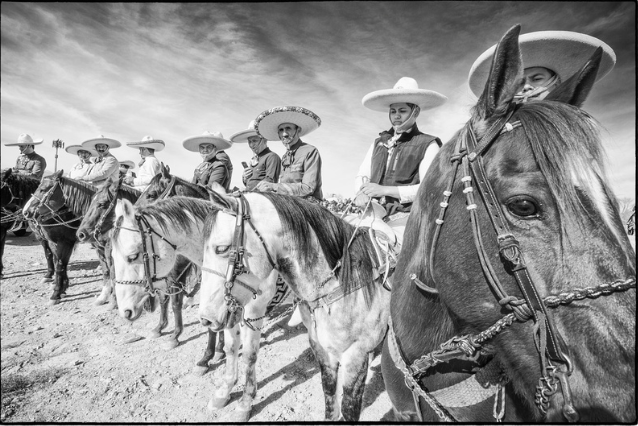

In a series called “Charro, A Portrait to a Way of Life,” Gómez-Morales depicts the charro culture: men and women both in beautiful clothing, displaying expert horsemanship and showmanship. Many would understand the charro as a “Mexican cowboy,” but he bristles at the term.

“I hate to use that; it seems like such a dumbing-down term,” he says. “First of all, the original cowboy was Mexican. It seems redundant to say ‘Mexican cowboy.'”

The word “charro,” as he explains, doesn’t really have a direct English translation. The culture itself is a blending of that of Spanish colonizers, American Natives, and the indigenous peoples of Mexican.

“People forget that America is a continent, not just a country,” says Gómez-Morales. “Charro culture is a blend of all of those cultures that were in America.”

The sport itself evolved out of cowboys learning their skills on the ranches they worked—they would compete against each other to see which ranches had the best cowboys. After the Mexican Revolution many of the charros were displaced, but kept the culture alive to still have a connection to it. The charro costuming is adopted from traditional Spanish clothing from areas like Salamanca, which Mexican people adopted when the country was colonized by Spain. Further Spanish influence is seen in the gentility of the sport of charreada: it is very much a gentleman’s (and gentlewoman’s) sport.

Gómez-Morales remembers growing up watching and idolizing these charros. He bought a rope and would practice rope tricks on the street with his friends. But when he was 14 years old, his parents brought him to America, where the pressures of being an immigrant teenager in a new high school made him force himself to “fit it.” He distanced himself from these “Mexican” things he loved as a child and got into what was popular in Southern California at the time: 1980s mod culture, new wave music, the Smiths.

“I was huge into that scene. I needed to fit in,” he says. “I distanced myself from even identifying as Mexican.”

After high school he joined the Army. There, he says, he was part of a melting pot of cultures within his unit, mostly African American and Puerto Rican. One thing he enjoyed doing while he was stationed in Germany was speaking with an ice cream vendor from Spain. His Spanish was “completely different” when he got back from the Army because of that, he says. It was this experience, being SO far removed and disconnected from his heritage with his only connection to it being an elderly Spanish woman, which made him realize that he missed all of those things he had turned his back on. He missed who he was.

So he started listening to the music from his childhood again, and reconnecting to these things from his past. After earning degrees in fine art and photography in Detroit, he followed this desire to remember and honor his culture in his work as an artist.

“I came over when I was 14 so I remember my life in Mexico. I remember my friends,” Gómez-Morales says. “So me wanting to document who we are [as Mexican-Americans] was also to encourage other people to feel good about themselves. The whole reason I moved away from it was because I was embarrassed about it, with the name-calling like ‘wetback’ and things like that. I was ashamed of it. But now I want people to know what this cultural heritage is, and to be proud of who they are. Culture is culture. There is beauty in everything.”

In documenting charro culture, Gómez-Morales specifically wanted to highlight the beauty in it. It’s so much more than a cowboy competition, he explains: again, it’s a gentleman’s sport. The costuming is important. The mastery of the horsemanship is important. The way a man salutes when he comes into the arena is important. And women are also important in this otherwise predominantly male sport, performing synchronized horseback riding in elaborate dresses. His whole charro series is about showcasing all of that beauty.

Last year Gómez-Morales exhibited this series and had people coming up to him thanking him for creating it.

“They were saying, ‘Thank you for showing how beautiful our culture is.’ I’m doing this so they don’t feel so marginalized, because I know there are people who feel marginalized because I was one of them. I want people to know, you’re just as important as everyone else. You’re part of humanity. Just accept that.”

Gómez-Morales also explored another part of his cultural past and childhood in the deeply personal series, “Las Aventuras del Blue Demon.” As a child in Mexico he watched the Blue Demon, a famous luchador (professional masked wrestler) who starred in over two dozen “really hokey and weird” action/horror/sci-fi movies in the 1960s and ’70s that were pretty much what ALL the kids watched when Gómez-Morales was growing up.

His Blue Demon series was autobiographical, and he used his son as his masked model to recreate some of his most painful memories of loneliness and forced assimilation as an adolescent. The series is mostly about his feeling of isolation after coming to America. The mask of his childhood hero is a metaphor for the strength he needed in his youth, and having his son wear it and be the subject of the series symbolizes his own healing process and hope for the future.

All of this, he says, is exploring “the idea of who I am and what I come from.” What does it mean to be American? What does it mean to be Mexican? What makes a person’s identity? What makes you who you are?

“We’re all so connected and we don’t see it,” he says. He took a home genealogy test kit, which for him was just another way of questioning his own identity and trying to understand it. He found out that he is 25 percent Native American and over 70 percent European, including 10 percent British and 12 percent Italian.

“But,” he continues, “people in this country don’t see me as that; they see me as Mexican. When you talk to Anglos they’re very aware of who their ancestors are—they’ll say they’re Polish or Russian or Irish or Italian—whereas Mexicans, before these genealogy tests, we had no idea. We always referred to ourselves as just being Mexican. We didn’t know we had family from Spain, that we’re not just Mexican but part of this larger global culture. But it’s all about identity, and what you yourself identify with, and how others define you.”

Gómez-Morales feels that, as an artist, his work should either make a statement or be some sort of documentation of who he is. That doesn’t just refer to cultural or ethnic identity; one of his most personal works is a photo series documenting his mother taking care of his father while he was in the late stages of Alzheimer’s (he has since passed away). The series, titled “Una Historia de Amor” (a love story), is full of images that are often heartbreaking, even painful to look at, but at its core it is about love.

“While I was shooting my dad it became almost about the relationship between Mom and Dad and this very strong connection they have. It became a love story, instead of being about the disease,” he says. “There was a big reward in a way for me because I realized how close my parents were, and through this project I was able to see that.”

This was in 2008. In 2017, his mother was also diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Now he is creating pieces in homage to her.

“I’m trying to work on some things with her to help her but also to bring awareness to the disease,” he says. “These pieces are a love letter from me to her.”

He is currently working on a cookbook concept, having his mom write recipes with stories to go along with them to keep her brain active and to keep her mentally stimulated and engaged. Along with these he is also writing his own personal stories to go along with them—memories of these recipes from his childhood and of his mom when he was growing up.

“I eventually want to put it all together as a cookbook, and that will be a gift to her children, her grandchildren, and her great grandchildren—she has over 60 now.”

A mixed media piece entitled Hasta Con Alzheimer’s te Amare depicts his mother as a Virgin Mary-like figure. On a photograph of her with her hands folded as she looks off into the distance, he painted a gold heart (because she has a “heart of gold,” but also referencing imagery often related to the Virgin Mary in Catholicism) and on her forehead rests a “crown” of broken pencils. Her mouth is smeared shut with gold paint. Underneath the photo etched in wood are the words, “Siempre te amare:” “I’ll always love you.”

“This piece is about communicating the loss of her ability to communicate,” explains Gómez-Morales. “The tips of the pencils are worn. Some are gone. Essentially it’s about communication, but it’s also about her connection to the Virgin Mary because my mom is Catholic and this represents her devotion to the Virgin Mary and the humility she represents. I wanted to touch on that connection my mom has to her, but also the idea of the humility behind that.”

He intends to create a whole series honoring his mother, and hopes to bring some awareness to the disease by creating pieces that are also meaningful to others.

Not everything he creates is quite so heavy: The series “Las Vegas Boulevard” is simply a photographic exploration of one of the most famous roads in the country, beginning with blank desert that turns into rural communities before morphing briefly into the infamous Strip, then running through industrial parks and blighted areas before going past Nellis Air Force Base and the Las Vegas Motor Speedway, then turning back into blank desert again.

“It’s such a diverse, weird street. How can you not photograph something like that?” The historical importance and general bizarreness of Las Vegas Boulevard fascinates him, and he enjoys commenting on the un-reality of Las Vegas by juxtaposing some of the images against each other in the surrealist series “This is Not America.”

Still, even these photos are about identity: The identity of a street; the identity of a city; the identity of America. In all of his work, Gómez-Morales is exploring who he is, where he is, and what he is, sometimes playfully, often emotionally, and at times devastatingly.

Featured image: Trying to Seceed, from “Las Aventuras del Blue Demon” by J. Antonio Gómez-Morales.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I don’t. [He laughs.] For some reason I don’t like to collaborate. I collaborate with students and basically guide them, but really that’s all about their work; it’s not about me. I’m coming more from the standpoint of guiding them and correcting them.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I always tell my students you should start with the things that speak to who you are and the things that interest you. If you like to race dirt bikes, tattoos, whatever, you should do something on that. If you’re interested in social issues like bringing awareness to LGBTQ issues, then definitely do something on that.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

There are so many contradictions within the industry and what people find value in sometimes it’s bizarre to me. I don’t sell much so I don’t necessarily charge much, but to me the things I find valuable are the things that are more personal. When I can connect on a personal level, that’s when I find value in it. I find a lot of value in the piece I did on my mom, and it doesn’t matter what other people think of it. Your most valuable possessions are your memories, which is why people say things like if their house was burning the first thing they would try to save would be their photographs. The most valuable things you have are your memories.

(4) How do you define success?

When people like you call me! [He laughs again.] Recently I had a student who had to write an essay about a piece of art for an art class she was taking, and she picked my piece at the Donna Bream Gallery. She kept thanking me for it. She told me she had gone back to look at it four or five times. That meant a lot. It’s not necessarily recognition, but the fact that somebody found it so compelling that she had to go back and look at it again, or when I had the charro exhibit, the comments the students made thanking me made me think, okay, this was the point in me making this show, to get that one person who feels marginalized in who he is and make him feel better about himself, because I went through that myself.

When I registered my daughter in school, one of the questions was, “What was your child’s first language?” I marked the “Spanish” box and because of that she had to take a special test [proving that she could read and write in English]. I asked them to please stop taking her out of class for this, she doesn’t need it, she’s top in her class. They told me she needed to be at a fifth grade reading level—she was in first grade! They didn’t take into account anything the teachers said, they didn’t look at her grades, it was just this box. So when she took the test and passed I got a congratulations letter, basically saying, “Congratulations, your daughter can now read,” which I found insulting. Now she’s in 7th grade and reads at a 12th grade reading level. It’s things like that, where people are marginalized just for checking a box. If I can touch people who feel marginalized for stupid stuff like that, and tell them, “You’re beautiful, this is who you are, your culture is just as valuable as everybody else’s and don’t question it.”

(5) How do you fund your work?

My work is self-funded, but right now I’m applying for grant dealing with Alzheimer’s. I applied before but didn’t get it, but when it’s the right time it will happen.