Street Art Making Mark on New Denver

Denver’s street art is attracting national recognition. How is the city’s booming mural scene helping soften the impact of rapid development and gentrification?

A carbon monoxide donut once hung low and dark around downtown Denver, fed by an uptick in drivers and intensified by the city’s altitude and geography. But today, Denver is a place where a visible pollution problem seems to have stayed behind in the last century, and where people are more likely to spot plumes of pressurized pigment than the city’s infamous “brown cloud.”

Street art — both the sanctioned, and the unlawful — is everywhere in so-called “New Denver,” and creeping into the suburbs. Born of hip-hop’s creative entrepreneurship and fueled by graffiti’s outlaw spirit, street artists in Denver find themselves at an unprecedented crossroads where municipal funding for public art includes dollars specifically earmarked for them; where museums and galleries have developed a taste for their vivid yet gritty aesthetic; and where a surge of new residents and businesses compose an audience eager for arts-driven community building and beautification.

Street-smart public art is helping to tell the story of New Denver in much the same way that Diego Rivera’s pre-Great Depression frescoes illuminated Mexico’s sociopolitical challenges. Similarly, artistic scenes splashed on the west side of the Berlin Wall in the 1970s and ’80s dramatized democratic defiance.

During Ireland’s “Troubles” of the late 20th century, murals in Dublin and Belfast reflected a proud people wracked by violence and division. And today, post-mortem outdoor portraits in Los Angeles immortalize entertainers, criminals, community leaders and historic Americans.

Visual ties that bind

“Historically, [street art and graffiti] was seen as an outlaw activity,” says Michael Chavez, the city’s public art manager. “Now people around Denver want it on their property.”

Chavez oversees the city’s Public Art Program, which was established in 1988 by Executive Order No. 92 under Mayor Federico Peña, and designates 1 percent of all public improvement project funds for artwork. Chavez also helps steer the Urban Arts Fund, a project that grew out of the city’s graffiti task force and creates commission opportunities for street artists.

Chavez believes the emerging look and feel of the city is intrinsically linked to these two initiatives. Not unlike Mural Arts Philadelphia, a 30-year-old municipal program that sets a high bar for art-driven community development, Denver’s mural program is “mature and sophisticated,” Chavez says. “It’s garnering national and international attention, and putting Denver on the map as a place to see really excellent street art.”

But what exactly is New Denver, besides a growing outdoor gallery? For one thing, it’s now among the country’s fastest-growing cities, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Denver grew by nearly 20,000 people from 2014 to 2015, which meant roughly 60 people relocated to the city every day.

The Rocky Mountains have always attracted people to Denver. But now transplants also are drawn by a healthy economy and, yes, legal marijuana. So far the city’s unemployment rate for 2016 is 3.3 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is lower than the previous year as well as the national average of 4.9 percent. At the same time, Denver’s housing prices have gone up 10 percent in the last year, according to Zillow.

And so, while snarled in one of the city’s increasingly common traffic jams, there’s a good chance that drivers can look up from a sea of out-of-state license plates and spot an artist’s vision splashed across concrete. These aren’t the Old West frontier scenes that dominated Colorado’s public and gallery art over the last couple of generations. Today’s Denver street art is decidedly more contemporary and urbane.

One place where locals can literally watch the city’s mural scene blossom is the Cherry Creek Trail, a 25-mile-long concrete artery that cuts through the city. Beginning in 2014, the Denver Public Art Program began updating this tagged and neglected bike path beneath Speer Boulevard with commissioned works by both local and national muralists.

“The more artwork we do down there, the more people tell me how much they love it,” Chavez says. “We could just stand down there and collect high fives all day.”

And just north of downtown in the River North (RiNo) Art District and Business Improvement District, public art has become a staple of new private construction projects.

“We have developers planning these large scale buildings and they want art to be a part of that,” says RiNo Art District co-founder and artist Tracy Weil. “Art is a common thread, and a way to activate community. Without it, you’re creating places that look like every other place. . . . It’s about empowering communities to do something differently.”

RiNo’s official designation as a Business Improvement District in 2015 resulted in thousands of additional dollars becoming available for community art events like Crush 2016, the weeklong mural festival in August that revolved around 75 street artists — the majority of whom were local — creating dozens of murals on and around the 2400 to 3400 blocks of Larimer Street.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” Weil says. “This army of artists came to Denver to make a massive statement and create something special.”

Crush began a handful of years ago as a scrappy effort to unite the city’s feuding graffiti crews. But with help from the RiNo BID, it’s become a capstone event that draws talent from across the country and conjures comparisons to the likes of Art Basel in Miami.

The mural movement also is sneaking outside the city limits. Consider West Colfax Mural Fest in Lakewood, a daylong event hosted by the 40 West Arts District.

“We have large and smaller scale murals completed in the days leading up to the festival,” says 40 West Program Manager Liz Black. “In conjunction with that, we have live painting on site, food trucks, live music, a beer garden and art vendors.”

Black says Mural Fest is successful and growing because the event highlights local businesses and artists.

“There’s beauty in mural art in that it can be seen and viewed by the public and not just at a gallery opening,” Black says. “It’s a great way to revitalize neighborhoods.”

Her organization marked its second annual Mural Fest in August, and has set the date of the next event for Sat. Aug. 12, 2017, at Lamar Station Plaza near Colfax Avenue and Pierce Street.

According to street art enthusiast and contraband sticker collector Mark Faulkner, RiNo and Lakewood’s 40 West corridor are just two pockets of what he calls “momentary art” around Denver. “In a moment, the city could come by and paint over it, or another artist could come along and screw you,” says Faulkner, who’s posted snapshots of more than 60,000 local street art murals, stickers, stencils and the like on social media using the moniker @DenverStickerMan.

Some other areas to sniff out outsider art include the I-70 underpass near the Purina factory on York Street, the South Platte River bike path, and beneath the I-25 flyover near Broadway. Faulkner also has chronicled outlaw art in Aurora, Englewood and Longmont.

From walls to skin to canvas

The rising profile of graffiti-informed commissioned murals sometimes spurs opportunities for artists that go beyond landing municipal commissions. Longtime Denver artist Jack Avila, 45, says he started scrawling on west Denver walls in the 1980s because, at the time, the graffiti around Barnum Park and Athmar Park opened the eyes of a kid who “liked to draw” to a world of artistic possibility. “I just fell in love with it,” recalls Avila, whose eye for art grew the farther his skateboard carried him into other regions of the city. He now creates more canvases and tattoos than outlaw murals.

And what is the distinction between graffiti and street art?

“Graffiti, to me, has always been a secret thing,” says Avila, who is better known as “Voice” in Denver’s arts community.

Tagging, or the act of leaving a mark or signature for reasons other than the aesthetic, further confuses people about the role that street art can play in community development. West Denver, with its lower-income, ethnic neighborhoods and sporadic gang activity, has struggled with the issue.

“Tagging vandalism is neither mild nor innocuous,” one west Denver resident wrote in a letter to city officials that was quoted in a Sept. 2013 Denver Post article. “It’s serious, it’s violent, it’s criminal, it’s destructive, it’s horrible.”

Further muddying the waters for artists like Avila, who learned to paint in school and the streets, is the fact that some artists who only have formal training are achieving financial success and public acclaim by appropriating a street art aesthetic.

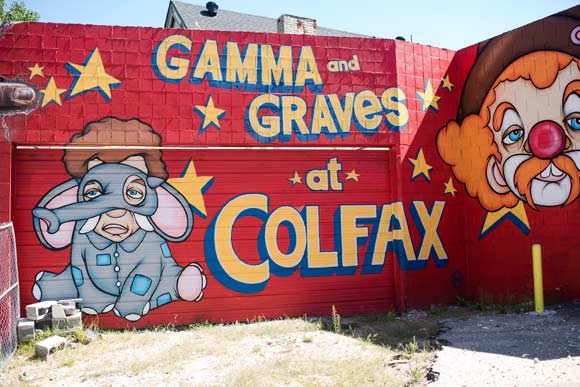

“Real graffiti is its own animal,” says the Denver artist Gamma Gallery. “It’s illegal, and you’re never going to change that.”

Gamma grew up loving comic books in Longmont. He started painting on walls about a decade ago simply because he needed a positive, creative outlet. His first mural was a portrait of Kurt Cobain forged on the side of a garage that belonged to his uncle.

“I didn’t think of what I was doing as a mural,” Gamma says. “I was just painting something for my neighborhood, and it took off.”

The more Gamma painted, the more his artwork got noticed. “People were coming into this vacant lot to see the artwork, and here and there I’d get a commission or I’d get invited to come and paint with other artists, and then eventually to other cities.”

Gamma now lives off of mural commissions. But he still creates art from the heart in the street.

Such humanity recently inspired a portrait on the side of a warehouse near 31st and Walnut streets. The image, taken from a photo on Facebook, was a close-up of the bloodied, mutilated face of well-known Denver MC Adam “Dent” Martinez, who in July was hit by a Ford F-450 truck while walking to cross the street at a busy Wheat Ridge intersection. The power of social media spread the story of the intrepid rapper’s very serious injuries, igniting a grassroots spark that culminated with Gamma’s graphic portrait.

But true street art can be fleeting, and so it follows that the artist’s homage to Dent’s seemingly miraculous recovery, is already gone. It was reportedly covered after nearby businesses owners deemed the accident victim’s image, complete with split skull and sliced lip, to be too gorey.

Pedro Barrios concedes that Denver’s graffiti meets public art mural scene helped fuel his own career.

“The city has started to embrace murals and designated money and space for them,” says Barrios, a gallery curator and painter who moved to Denver almost a decade ago.

Barrios, 35, is a self-trained artist who whet his appetite for street art during an extended stay in Europe as a college student. The trip brought him face to face with the work of such outsider art icons as Space Invader, Flying Fortress and Miss Van. The trip also included time “getting lost” in Amsterdam, where Barrios happened upon a mural in progress by the internationally-acclaimed street art crew The London Police. “I started talking to them and ended up spending three days at the mural site,” Barrios recalls.

Now he and frequent collaborator Jaime Molina are booked with commissioned projects.

“Murals make art accessible to people,” Barrios says of the appeal of large scale outdoor art in both public and private spaces. “There’s an instant connection, and there are no barriers.”

Metropolitan State College of Denver’s Center for Visual Art is a good place to observe the intersection of street art and fine art. Several murals dress up the building’s facade at 965 Santa Fe Dr. The collection includes a piece by the artist who’s been dubbed the country’s most influential street artist — Shepard Fairey — despite the fact that he’s classically trained and launched his career making skater tees, not graffiti.

CVA Managing Director and Curator Cecily Cullen laments the “ephemeral” nature of street art, particularly pieces plastered with the medium’s traditional adhesive: water-based wheatpaste.

“Art institutions of all sizes and missions tend to be intimidating to people,” says Cullen, who deems intention as the distinguishing factor between street art and graffiti. There’s a place in the art world for both, she says, which is why extemporaneous, sometimes competitive artwork blankets CVA’s alley-facing exterior wall.

“The city is playing a huge role in [legitimizing street art] because it’s looking for more businesspeople who see it as art, not as something to be upset about,” she says. “It reflects the personality of the city, and the influx of new people. It also balances out some of the more painful aspects of growth and development.”

Here’s a handy map detailing locations for works in the Denver Public Art Program:

Read more articles by Elana Ashanti Jefferson. Elana Ashanti Jefferson is a Denver native and longtime cultural affairs journalist. Her work has appeared in House Beautiful, Lucky, Popular Mechanics, The Denver Post and the Denver Business Journal.

Photos by Kara Pearson Gwinn, and courtesy Denver Arts & Venues and Gamma Acosta.

Launched during the 10th annual Denver Arts Week, this story is the first in a four-part series funded by the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and produced by Confluence Denver and Creative Exchange examining the impact of art and artists on Colorado’s evolving capital city.

[…] Partner Program at the McNichols Civic Center Building. Read stories as part of this series on graffiti and development in Denver, artist spaces and displacement, and percent for art […]

HOw do I contact the ARTIST(S)? I am beginning the process of putting together a benefit concert for George Floyd…an awareness raising/solidarity endeavor. Music and street art, etc.

My email is debgetsherdreams@yahoo.com Thank you kindly.