Marlina Gonzalez: The Craft of Storytelling

Marlina Gonzalez is part of a storytelling dynasty.

Her mother, Marina Feleo Gonzalez, is an award-winning screenwriter. Her brother, Jojo Gonzalez, acts onstage and onscreen. Her father, Arling Gonzalez, risked his life to report on the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines.

Marlina—a playwright, professor, artist, consultant, and professional listener of Filipina descent—eagerly furthers this lineage of seeking and sharing truths. She has held positions at a laundry list of Twin Cities arts organizations: the Walker Art Center, Twin Cities Public Television (TPT), Intermedia Arts, and now, Minnesota Public Radio, where she is a full-time community engagement specialist. She has also taught theater and Asian American studies at Augsburg University and the University of Minnesota.

“People go, ‘Do you ever sleep?” she says. “But I don’t feel stressed about it, because it doesn’t feel like there’s a lot of things I’m doing … At the very core of it is really looking for the true stories, especially the ones that we’re not hearing about; the ones that are not being recorded; the ones that are not being represented; and the ones that are being mangled.”

The early days

Gonzalez grew up in the Philippines, where she started writing stories and poems in the first grade. She studied theater and story-shaping through the Philippine Educational Theatre Association. As a high schooler, she ghostwrote TV episodes and radio scripts for her mother.

“I like a good challenge,” Gonzalez says. “So I wrote a [radio script] about this girl who couldn’t speak. My mom was like, ‘You’re submitting a radio script about a character who cannot speak?’ And I said yes, because I wanted to experiment [with] what it’s like to give presence to someone who can’t speak—but you can see the effect of this character’s presence through the people around her.”

After her family moved to the United States, Gonzalez continued prioritizing stories. She curated Asian American International Film Festival in New York for several years in the late 1980s. “It was such an empowering experience, because there was nothing, and then there was something,” she says. She’d scout films in Chinatown theaters, watching them without the aid of any English subtitles. Then, she’d learn more by calling producers and filmmakers from China to Sri Lanka to Canada. She recalls curating early work by Wayne Wang, who would go on to adapt The Joy Luck Club; future Beijing Olympics ceremony director Zhang Yimou; and Mississippi Masala director Mira Nair.

When the Walker Art Center recruited Gonzalez for an assistant curator position in 1991, she moved to the Twin Cities, where she sensed another opportunity to highlight seemingly absent communities. “When I first moved to Minnesota, it was around the time that there was hardly any Asian American community that you could see or know of,” she says. “And then I was involved with helping to found Asian American Renaissance, which no longer exists, but which gave birth to a lot of Asian American cultural organizations that we know today, like Pangea World Theater, Theater Mu, Asian Media Access, [Center for Hmong Arts and Culture (CHAT)], and Mizna.”

Some of the relationships Gonzalez formed in that time are still active today. The leaders of Pangea World Theater—spouses Meena Natarajan and Dipankar Mukherjee—met Gonzalez through Asian American Renaissance in the ‘90s. “We connected immediately,” Natarajan writes, calling Gonzalez a “creative firehouse” and “critical thinker.”

“Marlina…is connected deeply to her own culture and language, just as she is enmeshed in the fabric of the U.S.—[a] brilliant artist who deserves every recognition,” Natarajan writes.

Looking into negative space

Gonzalez says she’s drawn toward the concept of “negative space”: in visual art, the area around and between a subject. Negative space is often described as “empty” or “blank.” In this way of thinking, an individual receives more attention than their environment, and speech dominates silence. But for Gonzalez, negative space is a field of untold value.

“I think that the Western way of thinking about things is: It’s present when it’s visible. Measurable. Quantifiable. Audible. But we forget that there’s a lot more that is not picked up through sensory experiences alone. And that’s where an artist comes in, finding the ways to create that world beyond the sensory experience.”

Gonzalez also conceptualizes negative space as the constellations of stories outside current dominant narratives. She wrote Isla Tuliro, a play in English, Tagalog, and Spanish, about the colonization of an island and the islanders’ ensuing confusion. “Tuliro,” according to Gonzalez, is the Tagalog word for the discombobulating “sensation of having somebody clap you between the ears.”

Natarajan codirected Isla Tuliro for Pangea World Theater and Teatro del Pueblo in 2018. “Marlina examines the politics of space and what gets centrality,” she says. “[Isla Tuliro] was a treat, taking place as it did in multiple languages—exploring and examining colonization in a very unique way—through the politics of language. It also focused on the people who are not talked about, who are invisible in history, who have been erased.”

Family history

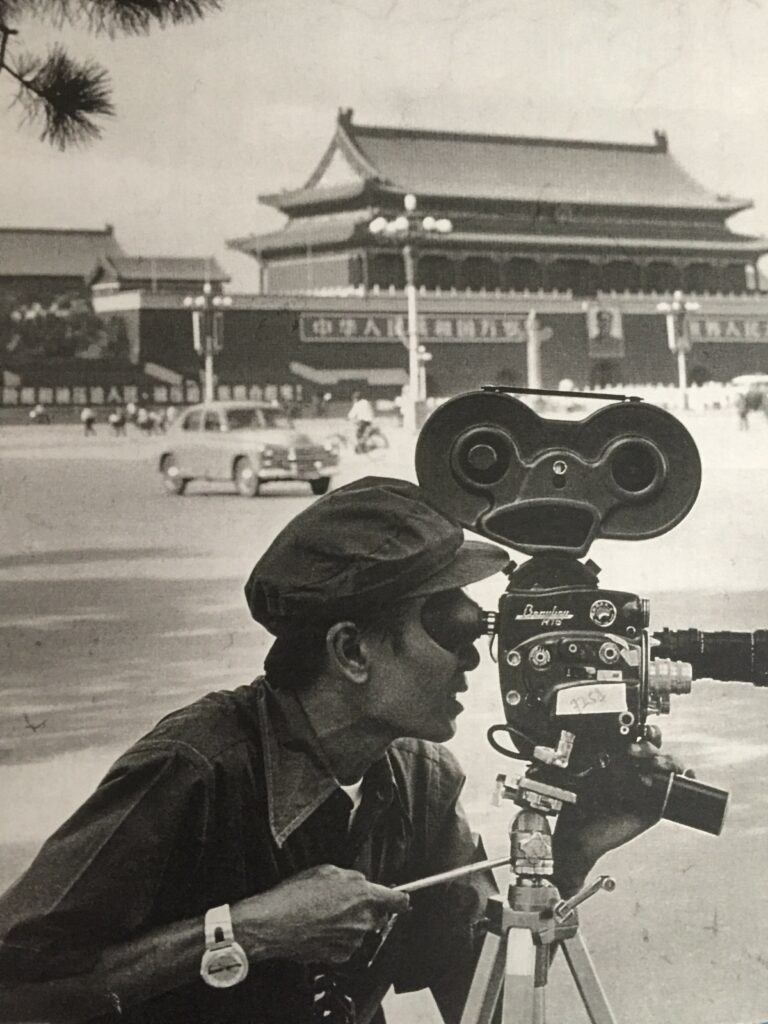

Gonzalez’s immersion in the craft and politics of storytelling dates back to her childhood. Her father, Arling, was an NBC correspondent in the Philippines in the 1970s. The country’s president, Ferdinand Marcos, had declared martial law in 1972, beginning a 14-year dictatorship.

“At a time when our streets were literally and figuratively exploding with demonstrations and protests against the Marcos dictatorship, [my father] had this protocol,” Marlina Gonzalez says. “I remember, even as a child, watching him driving toward a student demonstration … He had a black cloth, and he would chuck his hands in the black cloth, and his camera and his film canon. He would rip the edge of the film strip with his teeth, load his camera, jump out of the car, and film what was going on in the streets.”

Gonzalez’s father would develop the prints in the family’s film processing lab, then send them to Tokyo to be forwarded to the United States. But Gonzalez believes much of her father’s work never aired on U.S. television. “Because later on, people were like, ‘What? That was happening in the Philippines?’” she says. “Like, that’s been happening for 18 years! And people didn’t know … The choices of what stories to share—or what stories we’re authorized or vetted to tell—[are] often in the hands of the people that own the stations, the printing press, the whatnots. And that’s a really important part of me that prompts me to keep seeking real voices, real truth, from people that are absent.”

Future generations

Gonzalez’s daughter Diwa Tamrong carries on her family’s traditions of engaging imagination and working toward justice. She’s a youth educator based in New York, where she co-founded Arts in Parts, an environmental art organization, after the destruction of Hurricane Sandy. “They started teaching the kids by questioning, if they could rebuild their neighborhood, what would they do?” Gonzalez says. Program participants would visit the beach and pick up shards of wreckage, then create sculpture out of it. In addition to art, Tamrong has facilitated gardening and cooking classes for students, many of whom are kids of color.

Natarajan and Mukherjee know Tamrong from way back, when Tamrong performed in their show Shadowlines, which engaged with immigrant bias. “We … realized that the fire runs intergenerationally,” Natarajan writes. “[Marlina’s] daughter was pretty savvy about issues right from a young age—all due to Marlina’s influence and politics.”

Love for K-dramas

When Gonzalez isn’t working, she loves to watch Korean dramas.

“I think part of me is so attracted to it because they see the world very differently from how I grew up,” Gonzalez says. Her home country was Catholicized and colonized by Spain, then colonized by the United States, while the Korean peninsula has a completely different history.

Gonzalez says, “The Korean drama has a narrative structure that collapses past, present, future; there’s always a philosophical undertone to it. And in the good ones, there’s a subversive twist, where—it might be about this [corporation] that gets toppled down by the people below because they were cheated. But it’s always about people, deconstructing untruths that are permeating in their lives … The most ordinary situations become so profound, at least from my writer point of view.”