Adrienne Doyle: Burn Something, Build Something

Which is more important: art or the people who make it?

Some say art eclipses its creators, and some artists sacrifice themselves for their work. But Adrienne Doyle, a curator, writer, and zine artist from Minneapolis, prioritizes people over production. Over the past decade, Doyle has co-organized the seven-person Burn Something artistic collective; created opportunities for artists of marginalized identities; and advocated against injustice. Care is at the heart of her practice. In fact, it’s care for herself that has inspired her latest project: a move from Minneapolis to Philadelphia.

Doyle grew up in Minneapolis—first on the Southside, then over North. Her mom drove school buses, and she spent significant time with her grandmother, a lifelong learner and Gemini. Her younger brother arrived just before her 10th birthday.

Doyle’s path has wound through many Twin Cities arts institutions. They first gained access to artmaking materials and mentorship through Juxtaposition Arts, the North Minneapolis nonprofit geared toward teens and young adults. While they were in school, they worked at the Walker Art Center as a gallery assistant.

All those institutions helped shape Doyle into who they are today, but one experience at the Walker proved especially incendiary. In late 2013, the Walker opened an exhibit called 9 Artists, which featured a white artist’s photograph of a painting with the n-word.

“I was guarding the gallery, watching a white man and his teenage daughter view [the] photos,” Doyle, who is Black, wrote in the Twin Cities Daily Planet in 2014. “They stopped in front of the [n-word] photo, talked and laughed at the photo, looked me in the eye and moved on. I was infuriated. I wanted to confront them and ask them what the hell was so funny, but it would have been inappropriate for me as a guard in a museum to interrogate a visitor.”

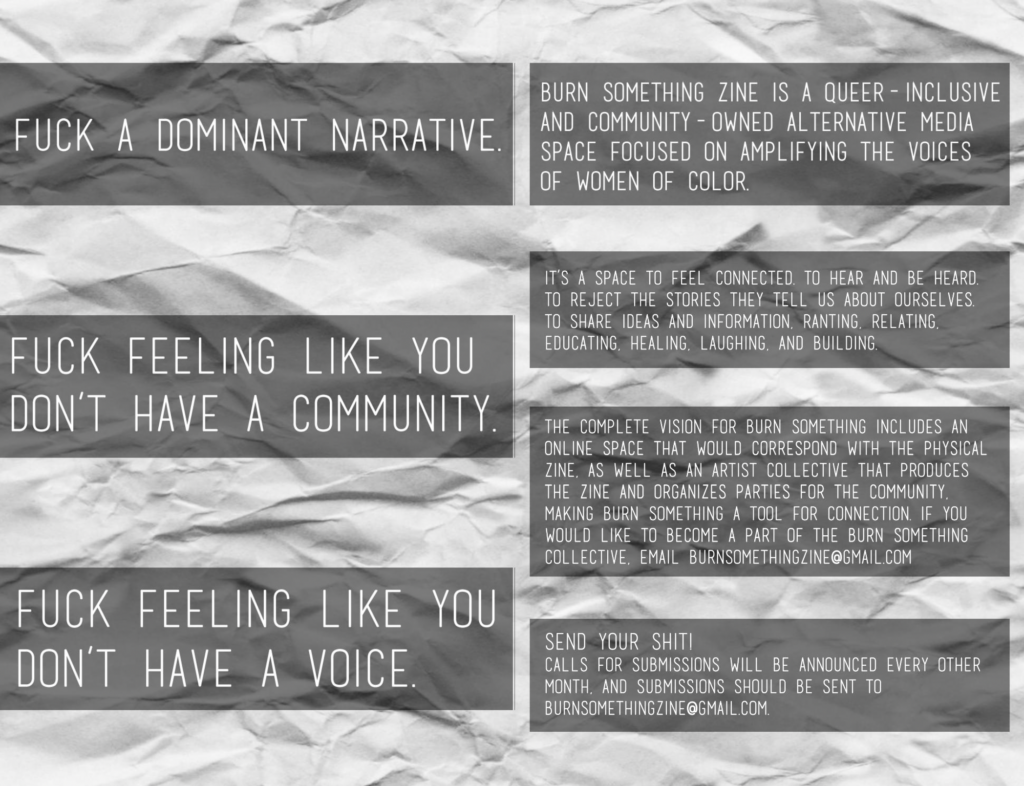

Instead, Doyle channeled her anger into founding a zine called Burn Something, which ran for six issues from 2014–2016. Doyle invited women and nonbinary people of color to submit their poetry, collage, and other art. She designed the pages on the computer and printed them out at work.

Speaking publicly against one of the country’s most prestigious arts centers—and creating a critical zine from within its walls—posed risks to Doyle, who was only 22 at the time. But her mentor at Juxtaposition Arts (JXTA), Caroline Kent, had been advising her to trust her power. “She was the most vocal supporter of Burn Something, even before I had even started,” Doyle says. “I was on the fence about whether or not I should do [the zine], because when you do something, people can have an opinion about it.” She laughs but emphasizes her point: “It has always felt really vulnerable to do public things for me.”

Doyle says, “The situation at the Walker illuminated to me that there are biases and power hierarchies built into the way that museums are run; the way museums think about artists and the work that they make; and all that. So I think my anger about that situation prompted me to create my own creative space [and] my own relationship to art, and art-making, and artists, and the power that they have: the narrative power, the healing power, the social power, the economic power, and the visionary power.”

Doyle would continue developing their power while participating in the Emerging Curators Institute, at which they shared a fellowship with Gabby Coll from 2019–2020. Coll and Doyle had attended middle school together for a short time, but they truly got to know each other as JXTA colleagues.

“We got really, really close really fast, because we worked our day jobs together and then also on this project, so that was very intense,” Coll says.

For the Emerging Curators Institute, Coll and Doyle reimagined Burn Something as an art exhibition. Because Doyle had founded the zine, Coll wondered if she’d be overreaching by helping expand the project. But by both of their accounts, Doyle had even been dreaming of sharing Burn Something for years.

Coll reflects, “So much of this work is about being in community and collaboration and supporting each other … it just made sense to bring more people into it.”

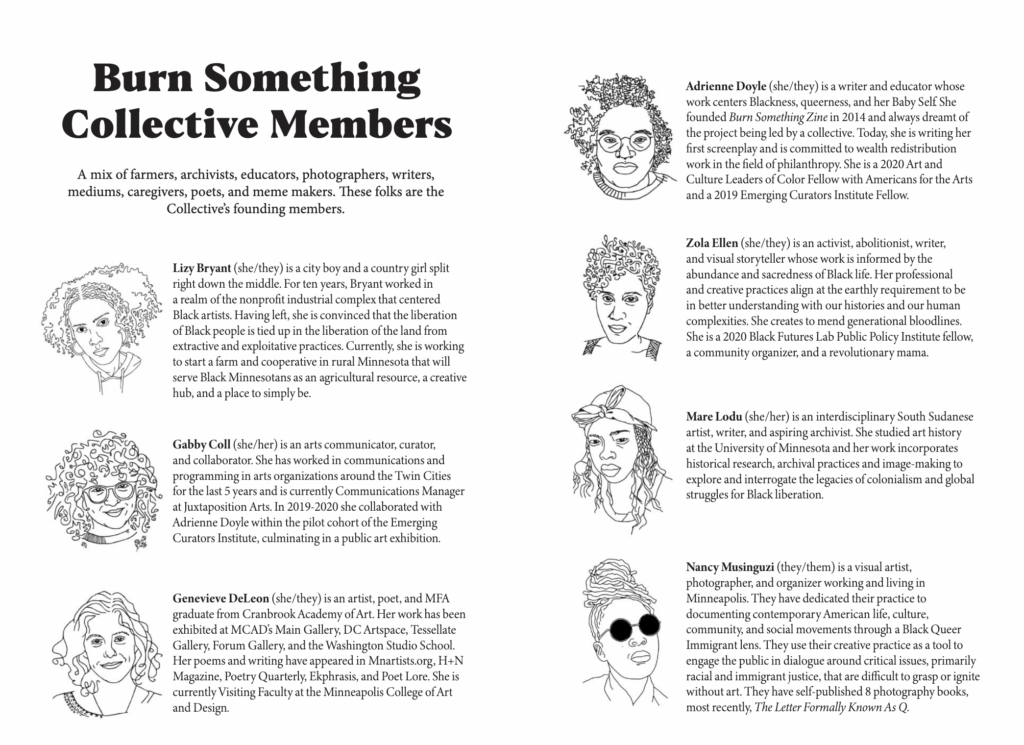

Burn Something expanded into a seven-member collective in February 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic and the murder of George Floyd. The group of seven—Doyle, Coll, Lizy Bryant, Genevieve DeLeon, Zola Ellen, Mare Lodu, and Nance Musinguzi—met at Doyle’s home and shared dinner, growing their friendships and discussing a collective vision.

“And so we entered the pandemic and the uprising with those relationships,” Doyle says. “I hear people talking about communities of care. And I think this collective is one of the only places where I’ve actually felt that in action, and the slowness that it requires, and the intention that it requires.”

Burn Something, the exhibition, opened in fall 2020 on the exterior of the Family Partnership building on Lake and Bloomington in South Minneapolis. The neighborhood had just experienced literal fires during the Minneapolis Uprising, sparked by a Minneapolis police officer’s murder of George Floyd. Burn Something Collective members adhered seven art pieces to the wooden boards covering the building’s windows, right behind the 14 bus stop.

In Sept. 2020, Doyle told Mplsart.com, “It’s been said that there is prescience in the name of this project, but I think the title is just a reflection. Racism has been burning communities of color in Minneapolis for generations.”

Burn Something presented a variety of media and aesthetics—Justice Jones’s primary-colored painting beside Zola Ellen’s black-and-white photographs, for example—which combined into a wallop of a show. As a curator, Doyle doesn’t worry so much about prescription or uniformity so much as clear communication.

Doyle says, “I look for heart. If I’m talking to the artist and listening to what they’re sharing with me—I look for that depth of feeling in their work.”

Coll and Doyle followed their Burn Something exhibition with the collective’s 2021 show, RECORD. Like Burn Something, RECORD was made of printed art hung on a building’s exterior. This time, the show lived at 1010 East Lake Street, just a block east of Midtown Global Market. RECORD featured playful, ingenious, and/or deeply distressed work from 10 femme, nonbinary, and/or trans Twin Cities artists from the Black diaspora.

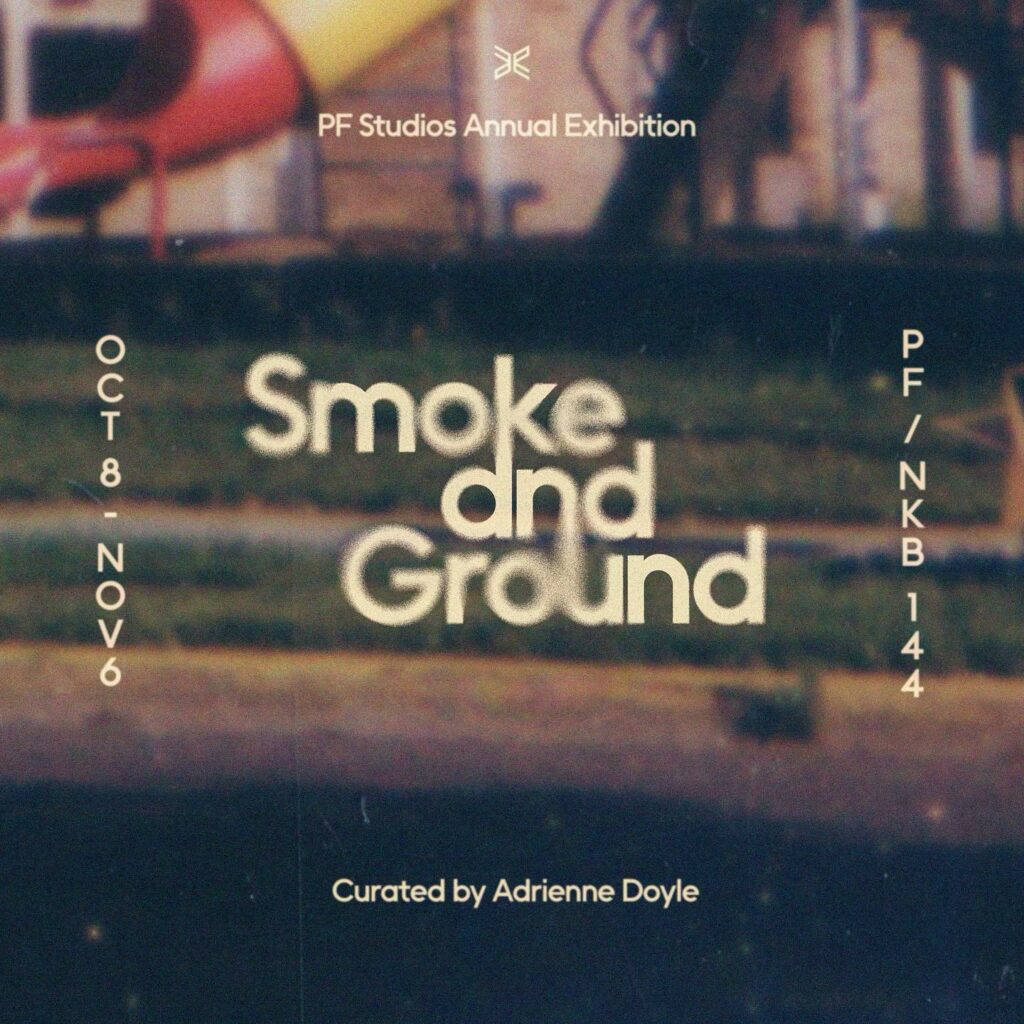

Doyle’s latest projects include Smoke and Ground, a place- and memory-inspired show running at Public Functionary’s Northrup King space until Nov. 6; Sovereign, a queer erotic zine from the Burn Something Collective; and an unpublished zine about police abolition and its relationship with Indigenous sovereignty.

Doyle would also like to develop a conflict repair process that’s slow, intentional, and restorative. The Burn Something Collective has experienced some interpersonal tensions, she says, although no major conflicts.

“I would really like to build a process in the case that larger things come up—whether that’s interpersonal conflict, or somebody doesn’t agree with the vision that we have for the rest of our work, or whatever. That’s one of the things I would really like to do as a part of centering radical, thoughtful care and as a core element of what we do together,” Doyle says.

They continue, “In the past, it might have been really easy for me to just cut off communication with someone who I felt was wrong. And now I have a therapist. Now I try to recognize or identify when I’m thinking punitively, in the context of conflict, and how I can replace that with other things—like taking space from a relationship but coming back to the issue. Or being more open about how I feel, rather than just shutting the person off.”

In November, Doyle will move away from Minneapolis for the first time. She’ll gain space from a still-grieving city, relocating to Philadelphia to seek new growth. Once she’s settled, five of the seven Burn Something Collective members will have moved away from the Twin Cities since 2020.

“It just means we’re a national art collective now,” Coll says, laughing.

But it doesn’t feel coincidental that so many artists of color have left Minneapolis in the past couple of years.

Sometimes, care looks like creating distance. Sometimes, it means making people dinner. Other times, it’s encouraging others to trust themselves or daring to speak out. And sometimes, it means burning something to the ground.