Maria de Los Angeles tells “Migration Stories”

June is Immigrant Heritage Month as well as Refugee Awareness Month. In solidarity and support, we will run a series of artist profiles and features this month about the experiences of undocumented artists, from a first-of-its-kind fellowship for undocumented artists to LGBTQ artists whose experiences coming out as queer gave them the language to then also “come out” as undocumented. Read the rest of this series here.

Maria de Los Angeles is a New York-based multidisciplinary artist with an Ivy League art education made possible through President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

Growing up in Tabasco, Mexico, she was always drawn to creating art. She was 11 years old when her family immigrated to the United States in 1999. She attended middle school in Santa Rosa, California, where she took art classes and really discovered and developed her creative passion. In high school she focused on sculpture and painting, then earned an Associate Degree in Fine Art from Santa Rosa Junior College.

Based on the strength of her work, de Los Angeles was able to get a scholarship to attend the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, where she earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting. From there she attended the Yale School of Art on a full scholarship, earning a Master of Fine Arts in painting and printmaking in 2015.

“I got into art and then art got me into university and graduate school,” she says. “Now I’m a professional artist and also an educator. Art can take you places.”

She now teaches at Pratt while also participating in artist residencies and exhibiting in group and solo shows around the country, including a solo show coming up in August called Tierra de Rosas at the Museum of Sonoma County in Santa Rosa—a kind of coming full-circle for her, as this is her first solo show in her adopted hometown of Santa Rosa.

de Los Angeles’s work focuses on issues of migration, identity, displacement, and otherness through drawing, painting, printmaking, and fashion. While her themes are often heavy, she also uses a lot of color, humor, and metaphor to make her work more playful and whimsical.

She creates large paintings full of color and symbolism, using landscapes, human figures, and religious imagery to depict family, border, and deportation scenes. Her work tends towards the allegorical, using fantastical images like flying angels and multiple visible layers of paint that give the impression of hidden imagery embedded in the paintings telling multiple narratives.

“I really like playing with things that aren’t quite possible, using humor or something sweet or floating figures,” she says. “For me it’s like storytelling. My paintings are very exuberant and full of life, and I invite people to spend time with them and read into them. My work is born out of joy for me. It’s a very playful part of my existence. I want to reach different audiences. I want five-year-old kids to be able to enjoy my work.”

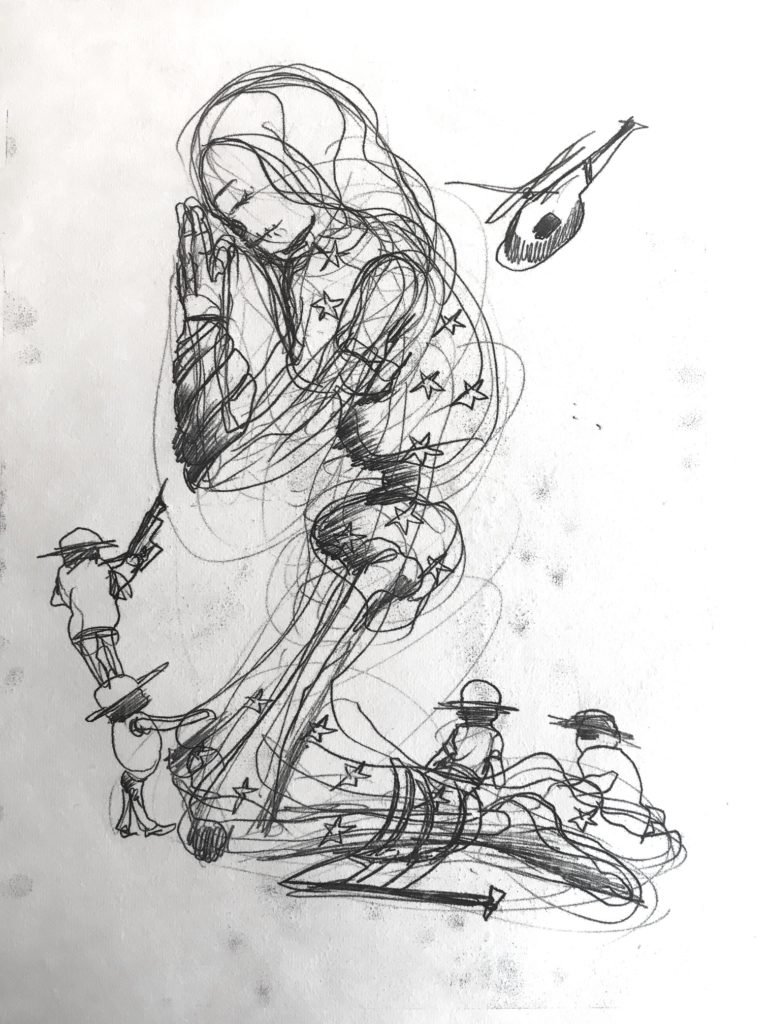

Her largest and longest ongoing project is her collection of drawings called Migration Stories, her own imaginative musings on space and land informed by her own experience growing up undocumented in the United States. Much like her paintings, the drawings are full of color and are meant to be playful and inviting, and they elicit a lot of emotional response.

“Migration Stories started as a way for me to come up with imagery to talk about who I was and what I was feeling—my own internal processes to really figure myself out growing up undocumented and coming of age in this country with that background,” she explains. “I was dealing with these things and had a lot to digest. For me, this was a way to do that. I’m not a writer; I draw.”

This ever-growing collection started out as a sketchbook of ideas for her paintings but has since become its own body of work. It includes mixed media prints and watercolors as well as nearly 2,000 sketchbook drawings, and she’ll present portions of this collection either framed separately as individual pieces or as a large-scale installation covering the walls of a room.

“It’s like reading my thoughts,” says de Los Angeles. “Drawing is very narrative-based. It’s not sequential. I don’t tell a story from beginning to end. It’s more like quotes or a scrambled poem.”

When she displays the drawings as a large installation, she’ll typically also include one of her fashion sculpture forms in the middle of the room with them.

These sculptures are wearable pieces of art that explore themes of the body, identity, citizenship, and stereotypes. They look like dresses or suits and are usually eight to nine feet long.

“It’s a kind of conversation, like talking about the body without the body there,” she says, “the idea of wearing something as a form to talk about all those conversations of race and identity.”

She started making these fashion forms when she was trying to take a self-portrait but kept feeling that what she was wearing wasn’t conveying what she wanted to say about herself. So she decided to create something that would.

“We all have a relationship to what we wear and how we portray ourselves, so for me this was kind of a natural vessel to have that conversation,” she says. “They’re also fun. It gives people a different entry point into the work. Anyone can relate to it; it’s not too stuck in the brain. They’re more accessible to anybody; anyone could put them on.”

The forms contain text, images, collages that include American flags and much of the same imagery that she uses in her paintings.

“My paintings and drawings inhabit these 3D forms in a way that’s the closest manifestation of who I am and how I feel,” says de Los Angeles. “I’m really proud of who I am and really proud be able to put on these garments.”

In addition to displaying these forms in exhibits, she’ll also use them in festival performances, fashion shows, and protests. They are meant to be worn, and they are meant to be interactive.

de Los Angeles’s work is inextricably tied to her own experience as an undocumented person in America, and while she does try to inject a sense of playful light-heartedness into much of her creations, they are also tinged with a creeping sense of foreboding (when they’re not outright nightmarish).

“I do like giving a voice to my own experience. It does come out in my work because it plays such a big role in who I’ve become,” she says. “In my drawings it’s more visible, but they can be read in different ways. But even if I wasn’t intentional about it sometimes, it’s always kind of there because it was such a huge part of my formative years.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I recently did a project with the Lower Eastside Girls Club of New York as an activity for the Every Woman Biennial. I made a dress in collaboration with the girls. They got to decide what was on it and to put their thoughts into it. The project facilitated their ability to express who they are and what they care for in the world. For my upcoming show in Santa Rosa I will do the same thing: a project with a group of students that will then be displayed in the show.

(2) How do you a start a project?

If it’s painting or drawing or my own garments, I just sort of begin. I add color or drape the form for the dress, then just get started. It’s really fun for me! Or if it’s a collaboration, I talk with the nonprofit and we decide together what the plan will be.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

I just want people to enjoy my work, live with it, and find an emotional connection to it.

(4) How do you define success?

In the big picture, I define success as just me being happy and me having a balance. A happy life would be the ultimate success. For me in my own work, it’s just finding satisfaction. It’s really about the process and my enjoyment of that process.

(5) How do you fund your work?

I teach, and I think teaching is really important. I market my work to galleries and shows and all that comes with that, and then [supplement the rest with] teaching. It’s a good balance for me.