Maamoul Press prints comics by Middle Eastern women, for Middle Eastern women (and everyone else, too)

Leila Abdelrazaq is a Palestinian author and illustrator living in Detroit. As an author and artist, she has tabled at zine and comics shows, but felt that there was room at her table—both literally and figuratively, as it were—for more than just her own work.

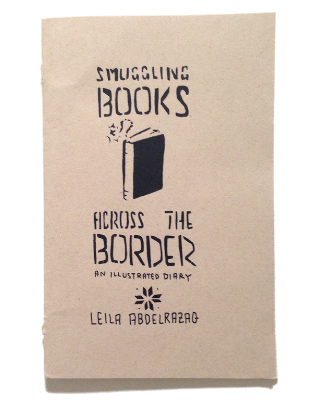

She launched Bigmouth Press & Comix in 2016 with that in mind: first starting as a blog profiling different Middle Eastern women authors and artists working in comics and illustration, then expanding into distribution of those same artists she had been highlighting. If it was too difficult to ship their work to the United States for distribution, she would just print it here herself. And so it was she found herself in the publishing business, too.

Abdelrazaq got more interested in publishing and decided it was something she wanted to pursue, but it was a lot of work for one person to do alone. So she approached Aya Krisht, another printmaking artist based in Dearborn, Michigan, about working together and combining their individual efforts to launch a multi-disciplinary collective that would publish the comics of Middle Eastern women artists and build a community around them. They also brought on a third collaborator, printmaker Zeinab Saab, originally from Detroit and now currently finishing her Master’s of Fine Arts in Chicago.

Thus, Maamoul Press was born.

“We’re all artists and bookmakers and printmakers, but I think the thing that interests us the most is exploring this overlap between comics, printmaking, and bookmaking and how storytelling ‘by us, for us’ is important, which was the whole idea behind Bigmouth,” says Abdelrazaq. “There are a lot of issues affecting our community—refugee and immigration topics people like to talk about and act like they’re experts on—and we often don’t have the space to talk about ourselves to ourselves, to not always have to explain our position to others but just talk to each other, and not always have to help others understand us but just understand ourselves.”

“A lot of times it might be difficult for people from our backgrounds to get their stories out there and published beyond just, ‘What is it like to be Arab in America?’ which is the typical thing you see published,” Krisht explains. “We want to be able to just tell our own stories about being human and about our lives without it always being this huge [identity statement or ethno-cultural lesson].”

“[Stories told by Middle Eastern women or other marginalized groups often have to be] either a confirmation or a challenge to someone’s political agenda; they can’t be just stories that are multidimensional and don’t play into tropes or tokenize us in certain ways,” Abdelrazaq adds. “There needs to be a multiplicity of stories and of voices, and sometimes those stories are going to be in conflict with each other and that’s okay because no one group is a monolith.”

One of their guiding principles with Maamoul Press is not just to feature “diversity” in terms of the authors themselves, but to also have a diversity of content and ideas as well.

“Maamoul is a platform that allows us to combine all of our skills, interests, and projects under one banner,” explains Krisht. “Through this we will publish more comics and get more comics out there while also providing workshops and exhibitions of artists from our same background as well as other marginalized backgrounds and help to foster opportunity in those communities.”

They’re about to wrap up their first eight-week Dearborn Comics Workshop for young women ages 16 and up. All of the participants are students in either high school or college and all of them are from Middle Eastern and North African backgrounds. Each Saturday the students attend the workshop in the morning followed by open studio time in the afternoon.

The eight-week series takes students through the full process of making a comic book, from conception to creation. Each week has a different theme, such as focusing on the relationship between image and text or learning the techniques of bookbinding. At the end of the workshop series, each artist will have created her own eight- to 16-page comics zine. The series culminates in a showcase at the 2nd Annual Book + Print Fest at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn where participants will have the opportunity to show and sell their work.

This workshop coincides with Abdelrazaq’s artist residency at the Arab American National Museum (AANM), through which she has studio space at the Dearborn City Hall Artspace Lofts.

“I’m trying to make this studio space more accessible to other people so it’s more than just ‘my’ space,” Abdelrazaq says. “There’s also a little zine library that people can borrow from and use as inspiration, and I invite people to leave their work in there and make it their own.”

The workshop is free for the students and provides them with a stipend for the production of their zine. The greater intention behind these workshops is to make comics accessible by making resources and tools available and creating opportunities for those who might not otherwise have them. The workshops also give Abdelrazaq and Krisht the chance to share all of their knowledge, excitement, and enthusiasm around comics with young Arab women who might not otherwise be exposed to the form or feel intimidated by the medium.

“I wasn’t formally trained in art but got into making comics on my own, and that’s the case for a lot of people in our community, which can be intimidating in comics and printmaking because it can certainly become an exclusive, pretentious boys club,” says Abdelrazaq. “It’s nice to have that space that people can make use of and take advantage of the fact that this is supposed to be more of an accessible art form.”

Their goal with Maamoul Press is not just to publish comics but to build a community around the work they’re doing. Abdelrazaq says that there is a huge comics and zine movement happening in the Middle East right now, and one of the things they want to do is bring that to people’s attention—that there’s all this “cool stuff” being produced all over the world and getting it out there for people all over the world to enjoy.

“That’s important because a lot of times there is a division between the Arab diaspora and the community at ‘home’ in the Arab world,” she explains. “If you’re a Lebanese person in Lebanon you’re considered ‘more’ Lebanese than a Lebanese person in America. So we’re bringing all of these different Arab experiences together.”

“We want to have an ongoing connection between comics in the Arab world and Arab artists in diaspora,” says Krisht. “Leila has published comics from the Arab world. In our workshops we have zines from people there. We all have connections to that community.”

Maamoul Press only just officially launched in January with the first Dearborn Comics Workshop series, but as they build capacity they plan to do more workshops and build up more resources that they can make available to people, in addition to printing books, tabling at shows, and perhaps hosting more shows or exhibits of their own.

“Maamoul is all about making this art form accessible to people and building a community around the work these artists are doing,” says Abdelrazaq. “Working with these artists, both in the workshops and from around the world, has been very inspiring to me.”

If you would like to support the Dearborn Comics Workshop, consider making a donation through their Go Fund Me page.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

Leila Abdelrazaq: From the beginning because I was already working on Bigmouth Press and asking Aya to be involved I knew I didn’t want to have the dynamic of, “This is my project that you’re working on.” We both have ownership in it; it’s our project. So that’s why we rethought through a lot of things and renamed it.

That’s important to me that everyone involved feels like they have ownership because it makes them more likely to help out and get involved. In order for people to take care of something it’s important that they know its theirs and take care of it; it just makes for a better working relationship where they feel they have ownership in what they’re involved with and not feel like there’s a hierarchy. That’s something I learned from organizing: When people don’t feel like they have ownership in something, they don’t step up.

Aya Krisht: I studied graphic design and worked as a designer and Leila has worked a lot in comics and been published, so just bringing our different experiences and backgrounds together has been a great collaborative process, bringing our different skillsets to whatever we’re working on to make it happen. For example, with the comics workshop, my background in comics is more theoretical—I wrote an undergrad thesis on comics and have studied them academically—where Leila has worked on them extensively as a creator, so she designs the hands-on components and I do the lectures.

(2) How do you a start a project?

LA: Really it’s just something I’m very excited about. You have to have the excitement to work on it.

AK: Like when we see an artist’s work and it’s really amazing.

LA: We just really need to feel passionate about the work we see. It’s about excitement and seeing the opportunity for a positive outcome.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

LA: There’s something very valuable about making space for a multiplicity of stories and making sure that people have access to the multiplicity of stories you’re trying to get out. There’s also something really valuable about making sure people have access to arts resources if they’re interested in that.

I think about that in terms of my own work: It’s important for people to hear this story so how do I get it out there? Who am I writing this for? It’s not just about people having access to resources to share those stories, but then for people to them engage with the stories and read them and share them with others. At their core comics are a very accessible forms of storytelling. Illustrator Isabella Rotman said that comics are inherently unpretentious: You can tell a nuanced, interesting, complicated story and make it accessible and not intimidating, and make it something people want to engage with.

AK: Comics are such a great tool for telling stories and making them accessible and making something people can get into and want to read. They also provide opportunities for people to gain skills to make their own comics and tell their own stories through the medium. Because we think this is such a great way for people to do that in a very unique way, sharing our knowledge and skills in how to do that and getting that knowledge out to people who might not necessarily have the opportunity to learn about the medium is core to our values.

(4) How do you define success?

AK: Any time someone connects with the work, that’s always a great feeling. Any time we feel people are connecting with what we’re doing or that we have opened an opportunity to someone in some way or made something possible for someone is a success.

LA: From tabling with Bigmouth Press at different comics and zine shows, the most impactful feelings of, “Okay, this is why I’m doing this” happen when a woman of color would encounter the table would say, “Oh my God, this is my story, I’m so happy to see representation here and not tokenization.”

There are so many different stories people have no idea are coming out of Middle East. For me, as a Palestinian artist, seeing other Palestinian artists is a success. Also when people say, “I learned something I didn’t understand before and this comic got me there”—that’s something that feels really great. I’ve had people reach out before saying, “I didn’t understand what was happening in Palestine before but this comic got me there.” When something helps you understand how politics affects people’s lives, when the comics help people understand that because politics are not separate from people’s lives, that is success.

AK: Especially when it’s something happening in another part of the world and showing a different perspective that they really have no idea about because they only see it from the Western media perspective.

(5) How do you fund your work?

LA: That’s a struggle.

AK: We still have a Go Fund Me going to support the comics workshop. We’ll do things like print sales to fund a specific project. There are sometimes grants that we might be able to apply for. Selling work and tabling at different festivals is also always a good way.

LA: Tabling at festivals is also a way of going into publishing. Publishing is not a moneymaker, so that’s not something we’re going into expecting to make money on. It’s not a way to make money. It’s possibly a way to get royalties started, but that’s not the important thing. The important thing to us is getting the work out there. Yes, we need to make money to keep our operation sustainable, but we also want to run it in a way that benefits the artists involved.

[…] Eastern Women (and Everyone Else, too).” Springboard Exchange, 22 Feb. 2019, https:// […]