Hip Hoppa Locka brings Muslim hip-hop culture to Northwest Miami

Miami Dade College is the largest educational institution in the country, spread out across eight campuses throughout Miami-Dade County. MDC’s moniker is “democracy’s college” because of its commitment to providing accessible, high-quality education and creating meaningful change in people’s lives.

The College’s student body is comprised of a diverse population, including Dreamers and first-generation immigrants. MDC seeks to offer opportunities for people to improve their lives through education to anyone who wants it, and its commitment to inclusivity and diversity also extends to its commitment to cultural enrichment and support. The college supports two of Miami’s massive annual cultural events with international scope – the Miami International Film Festival and the Miami Book Fair International – as well as the MDC Museum of Art + Design and the performing arts program MDC Live Arts.

MDC Live Arts was established in 1990 and was instrumental as a cultural pioneer in the city, pushing programming relevant to Miami’s diverse population rather than adhering to the more “classical” programming favored by cultural institutions around the country. There also weren’t many other cultural promoters at the time – this was more than a decade before Art Basel came to Miami Beach and Wynwood became Wynwood – so MDC Live Arts was able to set the tone and direction for cultural programming in Miami in many ways.

“The kind of work focused on changemaking has always been a part of our DNA,” says Kathryn Garcia, Executive Director of MDC Live Arts. In fact, MDC was recently named an Ashoka U “Changemaker Campus” because of its focus on instilling the ideals of changemaking amongst its student population.

“The College is really focused on trying to impact students on an individual level and empowering them to be changemakers in their community, showing them that anyone can do it,” Garcia says. “They’ve encouraged us to really refocus on this work and find these artists who are working with students and community organizations to move things forward socially.”

With that framework in mind, in recent years MDC Live Arts has presented “Trigger,” a hip-hop project about gun violence; “Holoscenes,” an outdoor installation addressing rising sea levels; and “Conscience Under Fire,” a theatre piece performed by four young veterans about their experience at war and returning home. That group has gone on to formalize as a theatre group, calling themselves Combat Hippies, and has since been awarded their own Knight grant and were commissioned by MDC Live Arts for a new piece premiering next season.

“These projects that really have life and get us excited find a way to come back again,” Garcia says. “The best is when they take hold through the people who participated in them [and continue on with a life of their own], like Combat Hippies.”

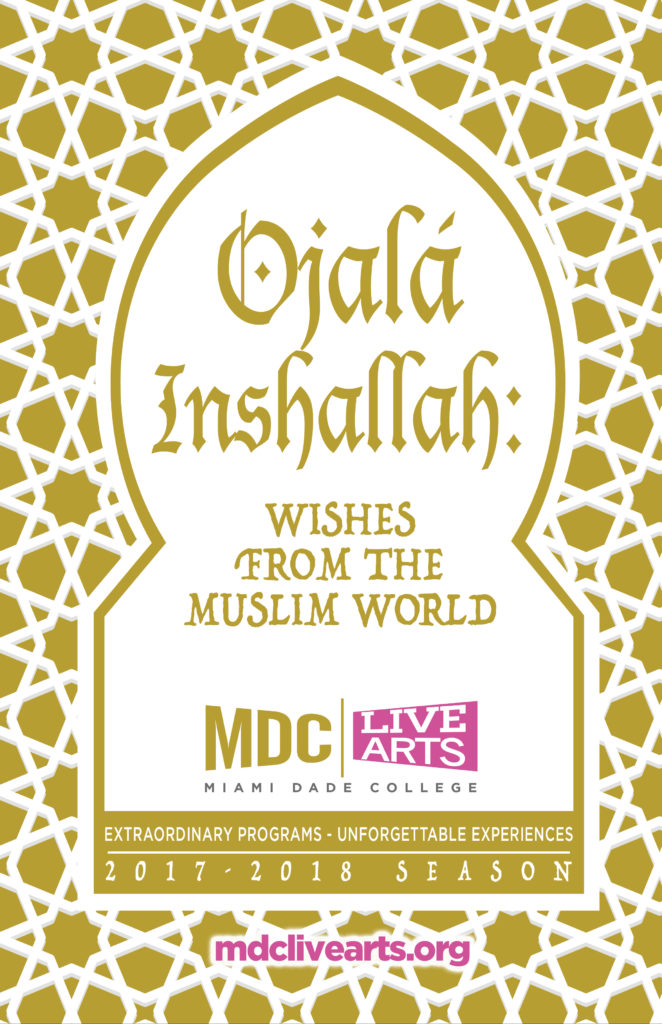

Now MDC Live Arts has dedicated their entire 2017-8 season to focus on the Muslim world in a series called “Ojalá Inshallah: Wishes from the Muslim World.”

The name itself is a reference to Miami’s culturally diverse population specifically as it intersects with the Muslim world: ojalá is a Spanish word meaning “to hope” or “to wish” and is a derivative of the Arabic word inshallah, “if Allah wills it.” This is just one of thousands of Spanish words that are derived from Arabic, an intentional call to the overlap between the Muslim world and Miami’s large Latino population.

The intention, Garcia says, is to show that “those differences everyone points to between [our cultures] are really not that great – we share more in common than we know.” With Miami being primarily Latino, she continues, they felt that an interesting starting point to connect people from different faiths and cultures would be through the things that bring them together, like a shared heritage and language, or shared cultural interests and experiences, like the world of hip-hop.

“We asked, ‘What are those hopes and things that can unify us?’ So we’re dedicating the whole season to different artists from around the country and world who are trying to break this idea of a monolithic Muslim identity and get to the point that we are all more than one thing. We are not just Cuban American or Muslim; we are also female or MCs or cultural workers. So we’re bringing in artists that break through stereotypes.”

One of the program’s upcoming projects is Hip Hoppa Locka, a Knight Arts Challenge 2017 winner.

This project brings an artist-in-residence program with Muslim hip-hop artists to the historic Opa-locka neighborhood to create work with local students around racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. And, in a further bucking of stereotypes, all three of the selected Muslim hip-hop artists are female.

“In terms of this whole project and season, we’ve been battling stereotypes and wanted to present some powerful women in the context of both hip-hop and Islam, where women are often portrayed as objects or as victims, so we really wanted to focus on female hip-hop artists from Muslim backgrounds to really blow people’s minds.”

The three artists who will be part of the two-week residency project beginning April 8 are Muslim in practice or culturally, and they each work in different hip-hop disciplines. Aja Black is an emcee from a Jamaican-Muslim background. B-girl Amirah Sackett breakdances in hijab. Cita Sadeli “CHELOVE” is a muralist from a Muslim family with an Indonesian background.

The artists will work with students from the Arts Academy of Excellence charter school in Opa-locka to create works that address issues in the community that the students want to address and focus on what tools they can leave behind after they’re gone.

“It’s not only empowering all of the students and community members who participate to have a voice in how they choose to tell their stories through dance, music, or visual art, but to also think about how it will have a legacy moving forward,” explains Garcia.

She also says that MDC Live Arts has wanted to do a project in Opa-locka in Northwest Miami for some time now. Originally built in the 1920s, Opa-locka was created as a 1001 Arabian Nights fantasy world in all its pure, unabashed Orientalist glory. Its origin point was steeped in stereotypes, and even the street names reflect it, with “Ali Baba” and “Aladdin” avenues and the like.

As a result, Opa-locka has the largest collection of Moorish revival architecture in the Western Hemisphere, with intricate Arabic architectural details like domes, minarets, and outside staircases. Twenty of the still-standing original buildings are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Unfortunately, the trajectory of the community in the time since it was built as a rich man’s fantasy world was one plagued by poverty, violence, and corruption. It has been considered the most dangerous community in Miami-Dade County and has long been on the verge of bankruptcy. The contrast between its creation as a place of fetishistic fantasy and its current reality is stark, but it is this juxtaposition that makes it a particularly interesting location for the artists of Hip Hoppa Locka to address some of the issues the community is currently facing.

The Opa-locka Community Development Corporation has been doing a lot of work recently using arts-based interventions to make transformational community change happen, and even received an ArtPlace grant for creative placemaking work. They have partnered with MDC Live Arts to present Hip Hoppa Locka, which will culminate in a community-wide celebration on April 21, during which the murals will be unveiled, the dance and spoken word students will showcase their work, and some additional special guests from the Muslim hip-hop world will make an appearance.

Hip-hop, Garcia says, is a global phenomenon, and is a way for people to connect with each other regardless of where they are from. Presenting three female Muslim hip-hop artists is also a way to get people to think differently about hip-hop; a person can be from Palestine or from Syria (or be a woman) and hip-hop can still be a very meaningful part of their identity.

Hip Hoppa Locka, as with every other project in this season’s Ojalá Inshallah series, is about using points of commonality to demystify the “otherness” of Muslim people and culture in order to challenge, and maybe even defeat, Islamophobic stereotypes.

“You can’t hate someone whose story you know,” Garcia says. “If we offer up these personal opportunities to get to know someone who has been stereotyped, some of that starts to wash away and maybe those stereotypes can be challenged. It’s very easy to demonize or stereotype someone who is Muslim because a lot of people think they don’t know anyone who is Muslim, but sometimes you have to look a bit deeper and then you’ll find they’re your neighbors and coworkers, and at the end of the day they’re regular people just like you and not some foreign thing to be afraid of. They face challenges just as you do.”

1. How do you like to collaborate?

I like to collaborate often! Resources go further and your impact is broadened with partners on board. Ideally collaborations are opportunities for organizations and individuals to join forces to make something great happen. I always think it’s really important to identify what’s in it for your partner – what is the “win” from their perspective. Part of collaborating is achieving shared goals, and advancing your partner’s interests as well as your own.

2. How do you a start a project?

With a good idea, of course – some sort of inspiration! I then go from the initial concept pretty quickly to the financial reality by sketching out a budget. That always leads me to practical next steps to figure out what is needed in order to realize the vision.

3. How do you talk about your value?

As an organization, we talk about our value in a couple of different ways. Within the context of Miami’s greater cultural community, we focus on taking on projects and addressing issues that otherwise aren’t being addressed, with the goal of contributing to the further growth of our field locally. And with students, we search out opportunities to embed encounters with artists at every possible turn, because you never know when or how someone will be impacted and what change it may produce in their lives or outlook.

4. How do you define success?

Pretty much in line with the way we lay out our values. Of course, if we have huge attendance or sales for a particular event, we celebrate that, as any arts organization would. But we are also careful to not just judge events and projects in those terms alone. Sometimes a smaller but deeply engaged audience is just as valuable.

5. How do you fund your work?

With a lot of blood, sweat and tears! No, but seriously, beyond the incredible efforts of a small yet mighty team, our funding is primarily a mix of government and foundation grants, ticket sales, and College support, which we are incredibly fortunate to have.