Define American is supporting undocumented artists through a first-of-its-kind fellowship

June is Immigrant Heritage Month as well as Refugee Awareness Month. In solidarity and support, we will run a series of artist profiles and features this month about the experiences of undocumented artists, from a first-of-its-kind fellowship for undocumented artists to LGBTQ artists whose experiences coming out as queer gave them the language to then also “come out” as undocumented. Read the rest of this series here.

Elnaz Javani had already been waiting five years for her visa interview when the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced last May that they were freezing visa interviews.

“It was a big shock,” she says. “I couldn’t move. I just kept thinking, ‘What’s going to happen to me?'”

During this time—six years total now—she hasn’t been able to leave the country, see her family (who are all still in Iran), or even have a full-time job, instead relying on the “gig economy” for unstable, impermanent, often low-paying work to eke out a living.

“It was too much stress and pressure. That was the moment that I realized the system is making me this vulnerable and feeling nothing inside. It made me feel like I am nothing, that I don’t have any power in this system. People don’t understand that because they’re not in it themselves. ”

Without a visa or other permanent resident documents, Javani is held in interminable limbo. She can’t get health insurance. She has to work harder as a part-time “gig” worker because she can’t get a more permanent, stable job, and she has to balance that chaotic and often unpredictable employment with her practice as an artist—that thing that is her life’s purpose and gives her a voice; that thing she would describe herself as first and foremost before “Iranian” or “undocumented.”

As an undocumented artist, Javani isn’t eligible for most grants, fellowships, or residencies, which are crucial sources of financial and professional support for most artists. A social security number is required on most applications, and she doesn’t have one. As an undocumented person she is in limbo, but she was also in limbo as an artist.

“I went though different phases mentally and emotionally,” she says. “I was sick. A big thing for me was figuring out how to see myself in this system and as an artist in this system.”

This is how she felt before she was accepted into the Undocumented Artist Fellowship, a first-of-its-kind artist fellowship specifically for undocumented artists presented by Define American, a nonprofit media and culture organization “that uses the power of story to transcend politics and shift the conversation about immigrants, identity, and citizenship in a changing America.”

Define American was founded by in 2011 by journalist, filmmaker, and immigration rights activist Jose Antonio Vargas with Jake Brewer, Jehmu Greene, and Alicia Menendez. The organization was based on taking risks—Vargas came out as undocumented the day the organization was born. Their mission is to make an impact in the world by defining what it means to be an American outside of the dominant voices that typically define it, and also what “American” has meant throughout our country’s history.

“We knew that in order to change the policies that impact people’s lives, we needed to spend significant time investing in the culture and how folks see immigrants and newcomers,” explains Ryan Eller, executive director of Define American. When the organization transitioned into a national nonprofit, they conducted an analysis of the immigrant freedom movement to assess what other nonprofits were doing and where the gaps were that they could fill with their expertise.

“We really landed on various aspects of media in terms of our expertise,” he says. “Throughout the years we have come to understand the creation of media in various forms to fall under the broad category of art—comedy, film, and spoken word, in addition to the traditional things people think of as art like music, painting, and sculpture. For us, it became this effort to define what it means to be an American and to get people to see themselves and what is possible for our country and our world through art.”

Define American started with a single artist in residence, the nationally-acclaimed poet Yosimar Reyes, who was in residence for two years.

“We believe artists should be free to do their art, be who they are, and not inhibit their creativity through certain boundaries,” says Eller. “Yosimar tells it like it is and that’s what we wanted him to be, even if things were provocative, because the best art is created with that sort of uninhibited freedom liberating artists to just create. It really expanded our vision so much of what was possible that we started talking to the Kresge Foundation about how we could expand beyond a single artist in residence to an entire fellowship that artists could be a part of.”

For this first year-long fellowship, the cohort consists of eight artists from six cities that represent the diversity that has made America America—the very same diversity that has made America great. There are undocumented artists from Mexico, yes, but there are also artists from countries that Americans don’t immediately think of when they think of undocumented persons—like Javani, who is from Iran, as well as others from Korea and Bulgaria.

Eller says they were worried that they would have to try to recruit people to apply; instead, with social media as the sole means of promotion, they had to cut off applications once they reached the mid-70s. The interview and selection process was lengthy and all conducted by committee.

“We were trying to look first for the very best artists who we thought are clearly about to take off if they’re just given some resources, a little support, and time to create in the way they envision,” says Eller. “From there we were interested in what types of community projects they wanted to do.”

Each of the fellows is partnered with another nonprofit organization in their respective cities to work on a community-based project during their fellowship.

“We wanted the fellowship to be somewhat place-based also, and not just undocumented artist fellows that we fund,” says Eller. “We wanted to link every fellow to a community-based arts organization where they live, so their primary work will be done with that organization.”

Karla Daniela Rosas is an illustrator originally from Nueva Laredo, Mexico who grew up in Southeastern Louisiana and now lives in New Orleans. She jointly applied for this fellowship with a fellow Louisianan, photographer and community organizer Fernando Lopez, who is also an undocumented artist originally from Michoacán, Mexico.

Together they’re working on a multimedia portrait series called “Caras vemos, corazones no sabemos” (“The Faces We See, the Hearts We Don’t”) in collaboration with the New Orleans nonprofit organization Take ‘Em Down NOLA, which works to remove all symbols of white supremacy in New Orleans. Take ‘Em Down has also taken stance on creating and sharing the histories of marginalized New Orleanians, making sure they’re documented because such stories tend to get lost in the dominant narrative.

“Here in New Orleans there are a lot of conversations around histories and histories being erased,” says Rosas, from Black families forced to live atop a toxic waste dump to the exploitation of immigrant labor in the Gulf’s seafood industry. “We want to bring attention to things like that because these stories are part of the history of the city.”

Rosas and Lopez are profiling individuals throughout the city in interviews and photographs, creating multidimensional portraits in which the person’s heart is painted over the top of their image.

“So much of our stories center on trauma. We want to focus on what drives people to do the things they do—the love, the anger, the joy,” Rosas says. “There are other things that make a person who they are aside from that trauma and we want to celebrate that, and also highlight that part of our history.”

They work closely with the individuals being profiled to remove the aspects of gaze and objectification as much as possible. The subjects collaborate on all of their portraits and how they are presented. Since some of the subjects are educators, Rosas hopes to be able to make this a traveling exhibit that can be brought into schools and perhaps have students participate in smaller versions of it. She and Lopez would also like to have a public event late this year for the community at large to see the exhibit and give the subjects a chance to talk about their profiles, the activist work they’re doing, and the work that still needs to be done.

This is the first fellowship Rosas has ever won. Though she is a DACA recipient, which means she has a social security number and can apply for programs that require just that, federally-funded grants often have a citizenship requirement as well, which excludes her. She is also hyper-aware of the funders behind various grants.

“I think it’s important to be critical of where the money comes from because I’m undocumented,” she says. “Being undocumented is so closely related to workers rights and immigrant rights, and I don’t want something funded by Walmart or the Shell Oil Company or some other organization that’s profiting off our exploitation.”

She additionally feels that being self-taught and not being formally trained at an art school is also a barrier because she doesn’t have “credentials” that are recognized and doesn’t know how to navigate the institutional side of the art world.

The Undocumented Artist Fellowship is also trying to address that, providing a number of different trainings, webinars, access to creators and artists further along in their careers who can offer their expertise, as well as Define American’s own expertise in communications, public relations, and events. In addition to the initial $5,000 award, fellows also receive training on professional skill development.

“One of the skills we’re trying to equip our fellows with is fundraising and development,” says Eller, “so we’re training them on grant writing and how to host fundraisers and do that development work that will help their career be sustained. From that they will apply for an additional $5,000 to $8,000 this fall in order to practice those grant writing skills.”

The fellowship also gives these artists national exposure through Define American’s website and their public events. The organization has hosted over 1,000 events in the last six years across the country, including speaking engagements at college campuses, film festivals, and their annual summit. Many of the fellows will attend the Define American Summit this October.

“We want to showcase to the larger world that art can really serve as a universal language and help us see ourselves and see what’s possible as we move forward with this vision of an inclusive America,” says Eller. “The idea is that the arts fellows will be showcasing their work to these communities and to other nonprofits and foundations in a way that sparks ideas about how they can involve artists in their efforts moving forward.”

Another benefit of the fellowship for the participating artists is being able to connect with other artists as well as with each other.

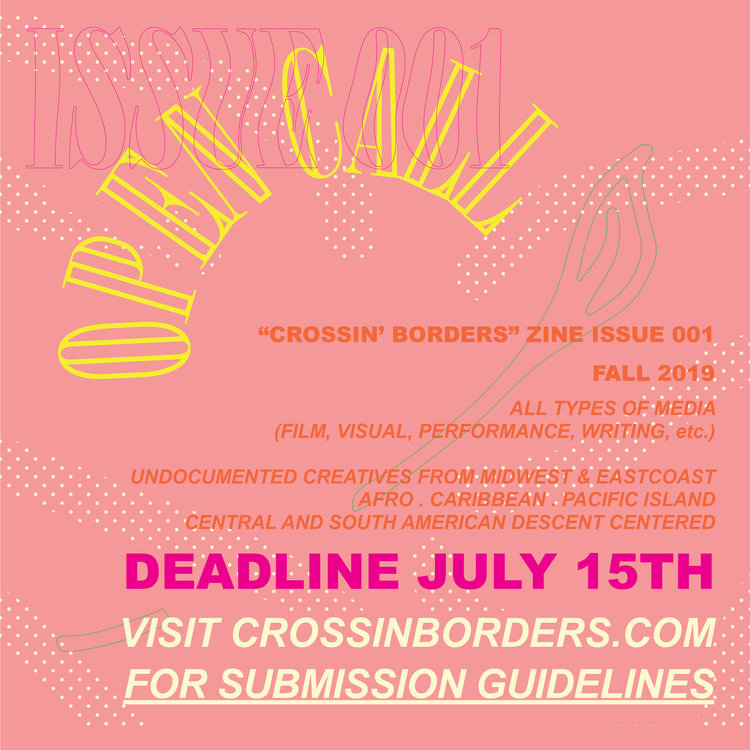

Brian Herrera, a graphic designer born in Veracruz, Mexico, has been involved in arts-based activism fighting for housing rights in Chicago for several years now, and is currently focused on highlighting queer artists of color in his work. His project for the fellowship is a publication called Crossin’ Borders in collaboration with Chicago’s Organized Communities Against Deportations. He believes it is the first publication centered on undocumented artists from the Midwest and East Coast, and with it he plans to explore the idea of “borders,” not in the physical sense of crossing a border, but in the metaphysical sense of the emotional borders and psychological turmoil that many immigrants and undocumented persons in this country experience.

“Crossing an actual border is not the full story of what it means to be an immigrant,” he says. “People come here in planes more than by crossing the southern border.”

Though he is focused on queer undocumented artists of color in his own work, the ‘zine will be more expansive in coverage. The first issue will prioritize artists of Afro-Caribbean, Pacific Island, and Central and South American descent. “These specific groups hold a unique narrative of what it means to be an immigrant because of the emphasis on the southern border,” he explains.

Herrera found out about the fellowship through his friend Yosimar Reyes—the same Yosimar Reyes who had been Define American’s first artist in residence. Herrera has found that the fellowship has connected him with artists around the country that he might not have otherwise ever found. Even growing up in Chicago was a somewhat isolating experience for him as a queer, undocumented artist who wasn’t “out” in either sense—he didn’t know anyone else in his community who shared his experience, and certainly didn’t know that there were so many other people throughout the country who did.

“I think the fellowship is amazing. There should be more opportunities like this because I feel like there’s a whole community that’s untapped,” Herrera says. “Define American has been doing a great job opening a platform to elevate these voices and it has been inspiring for me. It’s been motivating for me to see other undocumented artists as I navigate this fellowship and meet other people. Going through this fellowship has definitely also helped me look for more queer artists of color in the Midwest and on the East Coast.”

He says that Crossin’ Borders has been getting a lot of positive attention and he has been able to connect with a lot of undocumented artists, mostly through social media. “It’s been cool to see the type of work other undocumented people are doing, and I really hope to bring that same energy over here in the Midwest.”

He feels that this fellowship fills a void for undocumented artists, especially those who don’t live on the west coast and in California where there seem to be more opportunities for undocumented artists.

“I definitely see this as a missing pipeline,” he says. “I feel like there are other undocumented artists here in Chicago that I might even know. I’m sure there are tons, but people are not open about it. This is an amazing platform for undocumented artists to be more unapologetic.”

Javani wholeheartedly agrees.

“The fellowship was a huge help because I feel that there are people who see me and support me, and that was very hard for me before,” she says. “The support the fellowship has given me I haven’t had since I got here. This is the first time I’m getting that kind of support here in the U.S.—emotional support, and also the ability to take care of a lot of things. The money has given me the opportunity not to work much this summer and just focus on my practice.”

She was active in the arts scene in Iran, where she got involved with a women’s rights organization doing feminist work related to gender issues and violence while earning her BFA from the Tehran University of Art. She then came to America and earned an MFA from the Art Institute of Chicago on a full scholarship. Her work is shown around the world, though she is not able to leave the country to see it.

Coming from a feminist perspective and working on issues of women’s rights and gender violence deeply impacted her practice. Much of her work is about labor—the labor of women, the labor of immigrants and the undocumented, and the labor of artists. She works with different materials but especially loves fabric, in part because she would often help her father in his tailoring studio when she was growing up, but also because she is fascinated by fabric—the qualities of different fabrics, how intimate it feels, how closely tied to labor it is, how fabric is used to drape bodies and the history and culture associated with that, and how fabric can be used to communicate the narrative of her own life.

“I use these materials to explain my thoughts, emotions, and concerns,” she says. “In my work I’m trying to talk about this tension, the trauma. All my work is labor. It’s part of the labor that we all are going through—the long hours of work at the labor jobs we have as artists and the undocumented.”

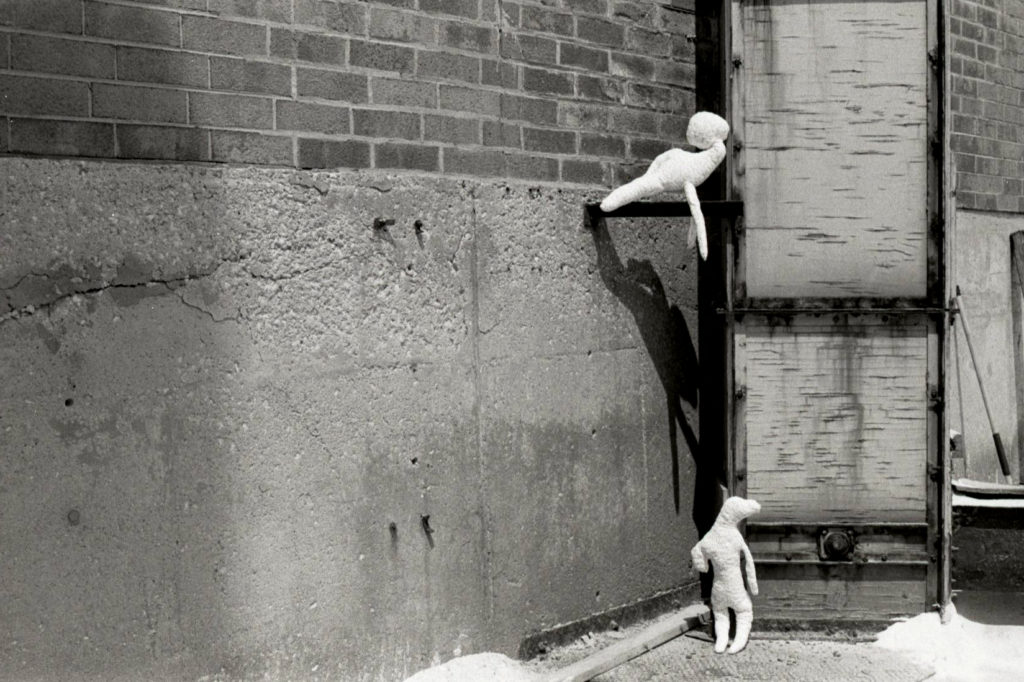

She is currently working on an ongoing project called My Effigies that show hand-sewn stuffed “bodies” made of white muslin fabric and covered in black Farsi calligraphy that she photographs “stuck” in different urban spaces in Chicago. These bodies are vaguely humanoid but distorted, and they are literally stuck—a reflection of how she herself feels. This project, she says, is also about showing labor, but mostly it’s about creating a sense of tension.

Her project for the fellowship will be a workshop with refugee women at the Hyde Park Art Center. The details are still being finalized, but the workshop will explore these same themes of labor, tension, trauma, gender, and immigration.

Although the last year especially has been very difficult for her, she has been doing the work she needed to do on herself so she could get back to making and creating. She was able to find resources to speak to a therapist and talk through her feelings of being forgotten, of being nothing. Embracing her own abilities as an artist made her feel empowered once again.

“I started getting back to working and actually feeling the power,” she says. “Especially what’s happening in the world, the tension between Iran and the U.S. is crazy and not being able to see my family at all because of the travel ban, this gave me perspective. I know my values and my abilities. I don’t have that privilege [of citizenship], but I have a lot of other things. I thought, okay, I have way more ability than other people even though they have the privilege. Believing in myself gave me that ability to decide for my life and not let the system push me down and hold me back.”

Javani previously felt like she didn’t have a voice, but when she began to feel like she finally had her voice back as an immigrant, she also understood that what she was going through was something a lot of other people were also going through. And then she was accepted into the fellowship.

“Through this fellowship I’m seeing these people that I didn’t know existed,” she says. “It’s a great opportunity to meet them and know what they’re going through, and also meet people going through the same thing I am.”

Eller says that the committee that chose the fellows for this first cohort thought through different aspects of diversity that would make the cohort strong together so they could build important social bonds and also learn from one another.

Still, he emphasizes that this fellowship is about supporting talented artists, and not just supporting undocumented artists because they need it.

“I think there’s a misnomer when these types of projects get started that the fellowship is created because folks are undocumented and we need to support undocumented folks, but we want to underscore that this fellowship is made up of artists who we think are the next generation of really profound, successful creators throughout the country, and even the world—incredibly talented folks who just so happen to be undocumented,” he states. “We’re providing them with residencies because undocumented artists in particular have very limited opportunities for resources like this, and often wouldn’t have inroads to mentorships with community-based organizations or national figures or opportunities to expand their social network.”

Eller explains that many businesses and organizations think it’s a risk to work with undocumented Americans, but, he says, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

“That type of misunderstanding about the law and what’s possible has prevented a lot of organizations form working with undocumented people in the way that we do,” he says. “There is nothing preventing an organization from contracting with businesses owned by undocumented Americans. We hope this fellowship will be so innovative and game-changing and impactful that other organizations will be inspired to model it and provide fellowships to undocumented Americans.”

[…] By NICOLE RUPERSBURG for CREATIVE EXCHANGE Read Full Article HERE […]