Building Partnerships to Lead the Work

This profile is part of a three-part series that highlights the work of five NeighborWorks network organizations that pursued new or expanded partnerships with artists or arts-based organizations to better understand, elevate and address issues related to gentrification and displacement in their communities. Using creative methods, the partners developed shared goals and tested new community-driven strategies. These partnerships were supported by NeighborWorks America as part of its work to support creative community development and use the power of art, culture and creativity to catalyze social, physical and economic transformation, with consulting support on artist-led community development from Springboard for the Arts. Read part one here and read part three here.

- NeighborWorks Salt Lake and Mestizo Coffeehouse (Salt Lake City, Utah) planned a series of events highlighting the challenges incarceration poses to the community.

- Community Ventures Corporation and local artists (Lexington, Kentucky) created art highlighting the voices and history of the residents residing near the development of a new, large, mixed-use development.

- New Kensington Community Development Corporation and Portside Arts Center (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) partnered with local businesses on projects with local youth showcasing their neighborhood pride.

- East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) and Destiny Arts (Oakland, California) worked with youth in a dance residency program in a neighborhood undergoing change.

- Hudson River Housing and Arts Mid-Hudson (Poughkeepsie, New York) created a mentor-mentee artist program to create pieces illustrating gentrification.

For a learning cohort process supported by NeighborWorks America, community development organizations worked hand in hand with arts organizations as they re-imagined the future of their neighborhoods. What they found was often unexpected and revealed ways that the milestones found on the journey are just as important as the final destination.

Those milestones were not only markers of the work between the official cohort partners, but of the community relationships and partnerships that make the work possible. Driven in part by the pandemic, but also by the way opportunities emerged, a key to the work was to ask what else was needed and what else was possible with new and established relationships. Listening to youth and building exchange, engaging businesses in new ways, relying on community partners to give critical input — these were all important components in how the cohort’s projects progressed.

In the shadow of the coliseum: Reimagining an Oakland neighborhood

Take as an example how process was more important than product in a collaboration between two Oakland-based nonprofits: East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) and the Destiny Arts Center. As the Oakland A’s baseball team announced its intention to build a new ballpark, the two organizations sought to articulate a sense of place as the renovation of the Oakland Coliseum leaves a development vacuum in East Oakland.

Destiny Arts and EBALDC’s partnership goes back seven years, focused on an afterschool arts residency in a different part of the city. There was an interest in the two organizations working more closely together, and the housing project behind the A’s stadium seemed a good fit. The two organizations met monthly on a series of youth-led projects, with a goal that they would create a vision for the neighborhood that centered youth voice.

Because of the challenges presented by COVID-19, the project didn’t come to fruition as originally as planned. However, what the two groups got out of the process was a deeper sense of listening and partnership that they will take into the future.

Annie Ledbury, senior manager of Creative Community Development at EBALDC, has a background in design and architecture, while Mika Lemoine, a dance educator who was working with Destiny Arts Center, has expertise harnessing the creative power of young people using dance. For Ledbury, working with dance was a new terrain. “Dance is like a whole other part of the brain and body,” she said.

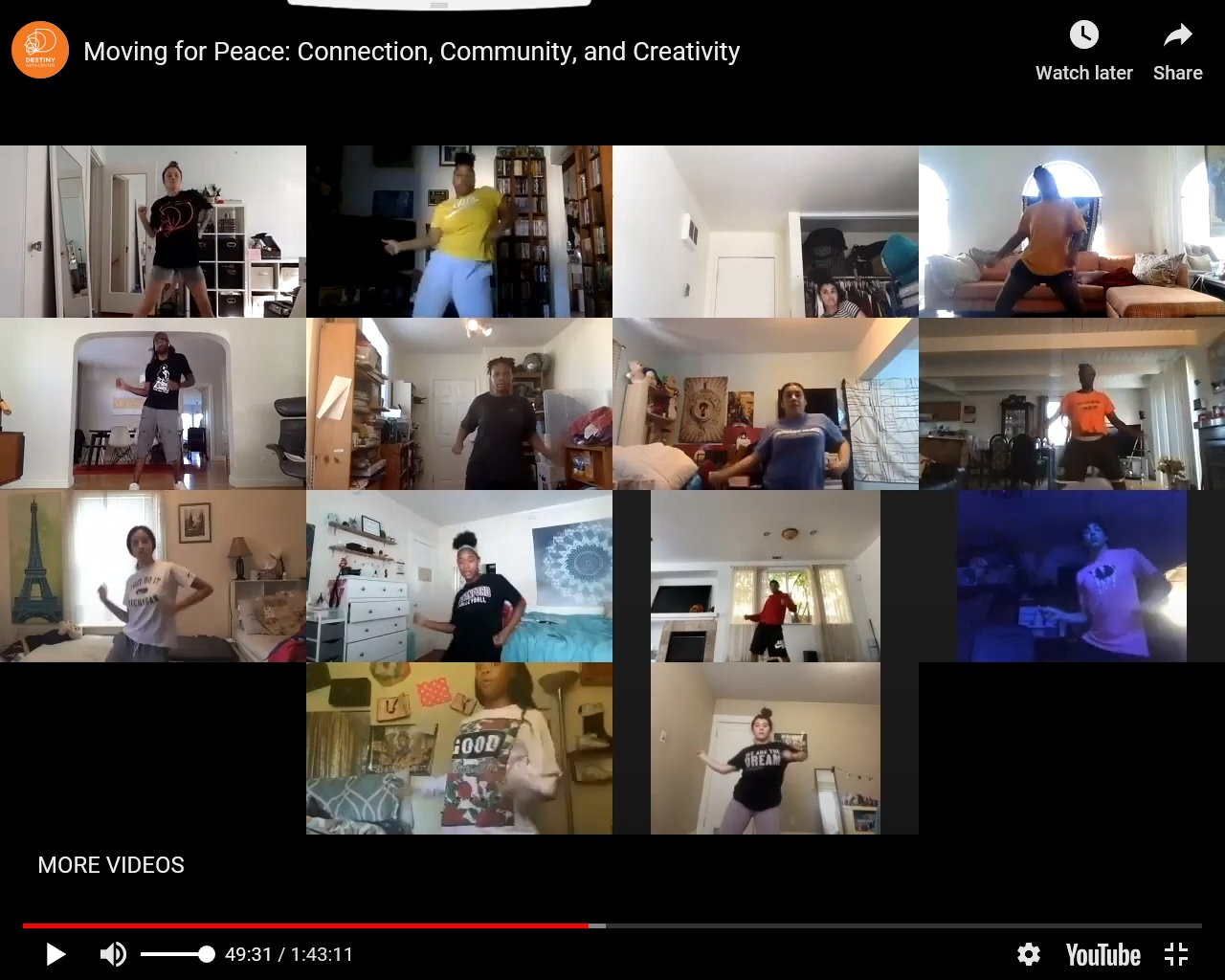

For Ledbury, the relationship building ended up being a key part of what the partner organizations gained from the project. The finished product was a block party, held virtually because of COVID-19, complete with a viral dance video. But Ledbury says the deepening understanding between the partner organizations went beyond that one event.

“A lot of the work itself was deepening the relationship between EBALDC and Destiny Arts,” Ledbury said. That relationship building has been incubating for many years, she said, but for this project grew in new ways, like in how both organizations thought about public space, displacement and leadership. “To me, the project itself was the process,” Ledbury said.

At the heart of the project was a housing complex called Lion’s Creek Crossings, in East Oakland’s Havenscourt neighborhood. The complex of 567 affordable housing units is a model of EBALDC’s Healthy Neighborhoods approach, complete with a restored creek, community garden, playgrounds, and lots of open green space. It’s located behind the coliseum, where the A’s used to play baseball.

The A’s have proposed replacing the stadium with a major market-rate development, which could bring much-needed resources and amenities to a neighborhood, but also makes the area vulnerable for displacing current residents. As the team no longer will be using the stadium, organizers, community members, and others are strategizing about keeping the integrity of the neighborhood as inevitable change occurs in that location’s next iteration.

“I do feel like it was a pretty emergent process,” Lemoine said of the relationship building between the organizations. “It was abundant.” Indeed, the cohort work recalled the writings of adrienne maree brown, author of Emergent Strategy, who has focused on the importance of relationship building as a key part of community-rooted work, and how collaborative systems end up being far more powerful than any individual entity.

Part of that emergent process was shifting and re-focusing as the partners learned about each other. For instance, typically at Destiny Arts, Lemoine works with mostly youth of color, many from queer families, who have been connected with the art center for some time. Often the young people she works with take on topics like Black Lives Matter or other current event issues as they create performance. Working with the young people who live at Lion’s Creek Crossings on a drop-in basis, however, brought up a whole different set of priorities the young people were confronting.

The youth in Lion’s Creek Crossings thought about public safety in different ways than the young dancers at Destiny Arts. “One of the things that I noticed is that when we would talk about issues of community safety, there really is a lack of education around what the history is, and why we’re in these situations that we’re in,” Lemoine said. “It seemed really important to have time to build community with the people who are going to be participating because you need to build trust if you’re going to talk about hard topics like race.”

Delilah, a Black teenager who was part of the program, found that the program brought her a better understanding of her neighbors and their backgrounds. “We are getting to know what their culture is,” she said.

In the project, Lemoine said she diverged from the work she typically does at Destiny Arts, which tends to have an end goal of a performance. Working with the youth at Lion’s Creek, Lemoine found joy in coming together, even when that coming together was messy.

“Meeting people where they are at and centering them and their voices and working with what you have is part of the creative process,” she said.

Lemoine added that the relationship-building work was about cultivating over the long-term, not just for this one project. “It’s a long-term thing,” Lemoine said. “Annie and I were also always negotiating that tension between just doing a project versus what the long term goals were.”

That’s not always an easy thing to sustain for nonprofits, in part because it can be difficult to get funders to support relationship building over multiple years. “Sometimes it’s not sexy,” Ledbury said. “People don’t want to necessarily fund a long, collaborative, adaptive, creative process, where you don’t know what the outcome is and you can’t write a cute report about it.”

“That’s what makes the NeighborWorks program so unique,” said Paul Singh, vice president of Community Initiatives at NeighborWorks America. “We understand that relationship building takes place over time.”

Finding the right balance as plans change

Building relationships is essential when plans change—for internal reasons like a personnel change, or external reasons like a global pandemic. That’s what New Kensington Community Development Corporation (NKCDC) found when they partnered with the Portside Arts Center in Philadelphia. Even as their cohort project shifted because of external circumstances, constant communication with each other, with partnering businesses, and with the community proved essential to ride the waves.

As a Commercial Corridor manager at NKCDC, Jake Norton works with small businesses along the organizations’ main commercial corridor area to help bring vitality to the intersection between New Kensington, Port Richmond, and Fishtown. The organization’s past work includes branding the Frankford Avenue corridor, dubbed an “arts avenue” as part of a branding process going back 15 years.

For a NeighborWorks cohort that paired NKCDC with Portside Arts Center, Norton was stepping outside of what he normally does with his job. “When I saw this opportunity come across, I thought it would be a good way to do something that’s a little bit different from my normal work and integrate some creative placemaking into what I do,” Norton said.

“Most of my projects before were focused on physical improvements, like getting security cameras or storefront improvement projects,” he said. “The idea of this partnership was to connect the young people living in the neighborhood with some of the community-owned businesses, opening them up to possibilities for their future,” Norton said. Working directly with Portside Arts Center was one thing but finding the right businesses to partner with an arts organization took some experimentation.

“It was a little bit rough at first,” he said. “After a few attempts, we realized that we definitely need business owners that have the capacity to work with us.” That’s not always easy, because business owners often have to be in their shops all day and don’t have the free time to partake in a project.

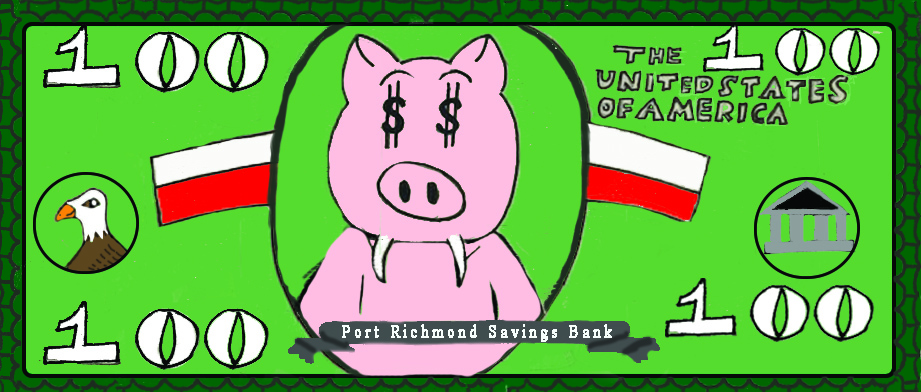

Eventually, NKCDC found a great relationship with Port Richmond Savings Bank, a 100-year-old bank in the midst of renovating its storefront. Initially, they planned to partner with Portside and NKCDC on a mural project, created by artists and youth from the art center. Because of the pandemic, the mural project was put on hold, but before that happened, the young people did take a field trip to the bank. “They met the representative we worked with, and he gave a whole spiel about banking,” Norton recalled. “He was fantastic with kids.” Participating children designed $100 bills to share their visions for the neighborhood, part of a larger effort to close the gap between the business community and the neighborhood.

“In bringing the children literally inside of these smaller community businesses, we’re opening them up to a whole world of possibilities for their future,” said Kelsie Lilly, an educator with Portside Arts Center. Besides the bank field trip, Lilly said the young people also took a trip to the local co-op.

Starting out in the partnership with Portside Art Center, Norton said he wasn’t exactly sure how the project would turn out. “I knew we promoted artists and events, and help them connect to resources,” he said, “but I kind of wanted to dive deeper into it.”

Things didn’t always go according to plan, but Norton said he learned to be flexible, and have a backup plan.

“You know, we kind of pivoted a few times on our project,” Norton said. “But I think we both took a lot away from the partnership.” Besides the bank, the project also involved a partnership with a local co-op. Originally, the two organizations had planned to host a gallery exhibition as part of their final project. Eventually the partnership evolved into a book project that featured different businesses from the neighborhood.

For Lilly, the book project facilitates a more accessible entry point to the art-making the organization was producing. That’s because the book will be available in places people not might normally look for art—in local businesses. “Having this book available at these different businesses makes it even more accessible than an art gallery,” Lilly said. “The books will be sold at these businesses that we wanted to collaborate with.” There was no doubt that COVID has been tough on the community and on projects. “But I think that how our project evolved because of new norms is really successful,” Lilly said.

Bringing in the community in Salt Lake City

Accessibility was also a key component of the work of Mestizo Coffeehouse, a gallery and coffee shop located in Salt Lake City that partnered with NeighborWorks Salt Lake.

The 12-year-old business, located in Salt Lake City’s Guadalupe neighborhood and developed by NeighborWorks Salt Lake, has as its mission to build community through art, said owner Dave Galvan. “It’s a labor of love,” Galvan said, describing the business that doubles as a gallery and coffee shop during normal times. The business has not been able to open since the start of the pandemic.

Galvan said re-opening the doors is in the works eventually. In the meantime, the relationship building continues as Mestizo and NeighborWorks Salt Lake take on issues of youth and adult incarceration, in part because the incarceration rates in the neighborhood surrounding the coffee shop were astronomical.

In developing the project, Galvan sat down with Jasmine Walton from NeighborWorks Salt Lake, to brainstorm. “We really wanted to do something that could embody the neighborhood that we serve and where we work,” Walton said.

The idea was to not only help folks caught in the school to prison system, but also create a vehicle for youth to have their voices heard and their artwork shown. “We really wanted to give those folks a platform to showcase their art,” Walton said. Collaborating with a local radio station on the project as well as a monthly magazine, NeighborWorks Salt Lake geared up to tackle issues of youth incarceration, adult incarceration, and mental health issues that are currently effecting youth in the community. “We see a lot of those issues come up, but there aren’t really platforms for them to talk about it or resources,” Walton said.

They also planned to partner with the local university on panel discussions taking place on open mic/art opening nights at the gallery. Because of COVID, both the expungement clinics and the panel discussions had to be postponed, Walton said. “We had talked about moving things online, but we decided for our community, doing it online wouldn’t be sufficient.” The plan currently is to host the clinics and panel events in 2021 when the weather permits an outdoor gathering, or COVID risk has lessened.

Walton has been impressed with people’s willingness to come to the table, even when some of the best ideas never come to fruition. “We had so many people reaching out asking how they could be involved with what we were doing,” she said.

That enthusiasm was sometimes more than the organization had a capacity to handle, but it was also a great boost. It shows how important it is to strengthen communication and connection to community for a project’s future success.

Key Takeaways

- Relationships building over time offer multiple points to build trust and work effectively.

- Creative placemaking projects succeed when they start from community ideas and include input from multiple stakeholders.

- Don’t presuppose the outcomes – the partnership may reveal new approaches or solutions, may shift focus, or may have outcomes that are not easily summarized.

Header photo: Community members gather for a lecture at Mestizo Coffeehouse in Salt Lake City.