Adaptations to Meet the Moment and Keep Engaged

This profile is part of a three-part series that highlights the work of five NeighborWorks network organizations that pursued new or expanded partnerships with artists or arts-based organizations to better understand, elevate and address issues related to gentrification and displacement in their communities. Using creative methods, the partners developed shared goals and tested new community-driven strategies. These partnerships were supported by NeighborWorks America as part of its work to support creative community development and use the power of art, culture and creativity to catalyze social, physical and economic transformation, with consulting support on artist-led community development from Springboard for the Arts. Read part one here and read part two here.

- NeighborWorks Salt Lake and Mestizo Coffeehouse (Salt Lake City, Utah) planned a series of events highlighting the challenges incarceration poses to the community.

- Community Ventures Corporation and local artists (Lexington, Kentucky) created art highlighting the voices and history of the residents residing near the development of a new, large, mixed-use development.

- New Kensington Community Development Corporation and Portside Arts Center (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) partnered with local businesses on projects with local youth showcasing their neighborhood pride.

- East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) and Destiny Arts (Oakland, California) worked with youth in a dance residency program in a neighborhood undergoing change.

- Hudson River Housing and Arts Mid-Hudson (Poughkeepsie, New York) created a mentor-mentee artist program to create pieces illustrating gentrification.

Creative placemaking, or placekeeping, is essentially a resiliency tool. Normally in discussions of placemaking or placekeeping, the stress or disturbance communities face have to do with economic factors, like displacement due to shifting development, or sometimes even environmental factors. In 2020, placekeeping projects designed by organizations in the NeighborWorks cohort faced an unanticipated outlier: the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most placekeeping projects involve bringing people together in physical space. That’s tough when the project is slated to take place during a shut-down order. When COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders began dropping in March, a number of cohort organizations found themselves having to shift their projects in order to keep their communities safe.

In New Kensington, Philadelphia, plans to create an art exhibition that highlighted an historic neighborhood transformed into a book project, through a partnership between New Kensington Community Development Corporation and Portside Arts Center. In Salt Lake City, NeighborWorks Salt Lake’s partnership with a local coffee shop and gallery, Mestizo Coffee, got put on permanent hold when the coffee shop shut down because of the pandemic.

But projects adapted, and through each example, one point become clear: the resiliency of communities relies on their ability to be adaptable. Even when something huge like a pandemic hits neighborhoods across the country, it’s the ability to rally, to shift, to transform, and to ultimately find new ways to come together that carry communities forward.

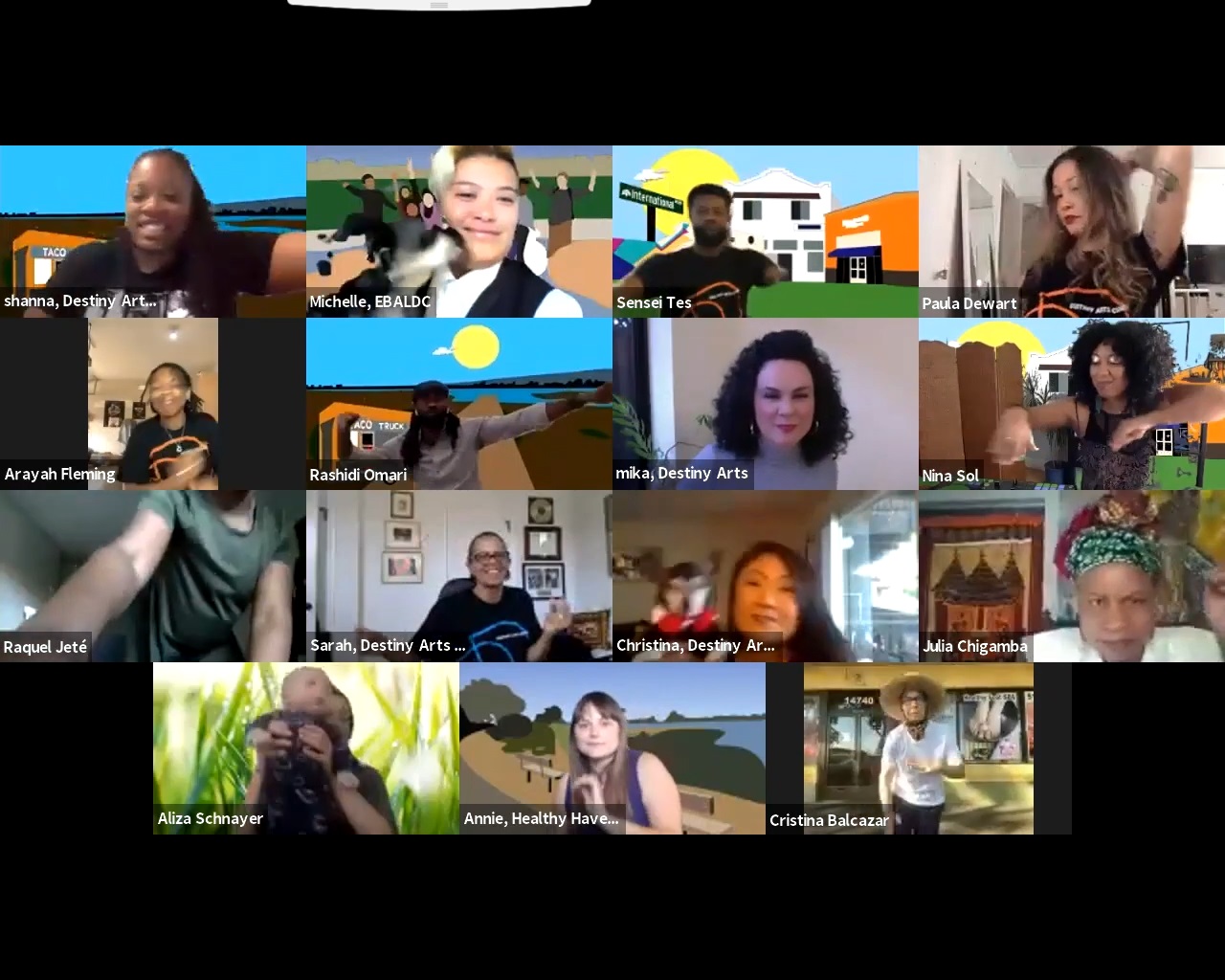

An online block party in Oakland

One partnership that took a bold adaptation move was East Bay Area Development Corporation (EBALDC) and Destiny Arts Center. The collaboration rested on an affordable housing complex called Lions Creek Crossings, located in the shadow of the recently vacated Oakland Coliseum. The site is on the largest piece of public land in Oakland, recently sold to a private entity for development.

The property has an after-school program for the young people who live in the center, many of whom attend local schools. The initial vision, according to Mika Lemoine, a dance educator with Destiny, was for the teens to design a community block party on the property. “It was going to be another way of saying, ‘We’re here, we’re in this neighborhood,’” Lemoine said.

Their plan to create a block party was thwarted due to the pandemic. But some quick thinking resulted in an alternative plan: a Zoom block party. The teens created a music video that showcased their dance skills, but also highlighted their feelings about where they live and their communities. The video streamed live at the Block Party virtual event.

“It was a reflection of our adaptation,” said Lemoine. It’s true that things didn’t work out the way the project designers originally intended. “But that is really normal in artistic collaborations,” Lemoine continued. “Things don’t pan out the way you thought, and adapting to that and being creative, and meeting people where they are at and centering them and their voices and working with what you have is totally part of the creative process.”

According to Lemoine, during the planning process, staff from the two organizations decided that, because both organizations do work but are not based in East Oakland, they needed to bring in partners that would help root the project in the neighborhood. Some of the partners included the Black Cultural Zone, an organization that focuses on preventing displacement in East Oakland, as well as Black-owned businesses. During the Block Party, these organizations and Black-owned businesses shared their work in community through short videos. “It was so cool because there were kind of like booths that you would have at a Block Party, except it was video,” Lemoine said.

“This was Black joy. This was Black community. It was a celebration of all these young people and this community. It felt like a building block. Maybe there was some access that was less because it was virtual, but there was also some access that was more because it was virtual.”

There were moments of serendipity too: happy accidents that might not have happened if the shelter in place hadn’t been in effect. “Weirdly, shelter in place made it possible to make a dance video,” Lemoine said. Normally, when many kids are gathered together, it can be difficult to make a video, which they had initially planned to do and project on the building during the block party. Meeting with only a few kids at a time helped keep things swimming along. “Living a virtual life also made it possible to create things that can occupy time and space forever,” Lemoine said.

Highlighting Kentucky’s artists online

In some cases, COVID-19 precautions opened up new avenues for growth in unexpected ways. That’s what happened in Lexington, Kentucky with an economic development organization called Community Ventures.

Community Ventures works with artists around Kentucky through its educational programs as well as offering marketing and promotion assistance. According to Mark Johnson, president of artistic operations for Community Ventures, COVID-19 hit at an unfortunate time for the Kentucky artists. It was right after winter as artists were gearing up to participate in the spring and summer art shows, which didn’t end up happening because of the pandemic. “They kind of got hit twice,” Johnson said. “They had to make investment for all of their materials and all of their time to create their artwork, but they didn’t have the opportunity to sell.”

To support those artists, Community Ventures doubled down on its e-commerce efforts. “For those that weren’t already engaged in e-commerce, we really worked with them to establish some type of online sales platform, whether that be through their own website, or by helping them establish an Etsy site,” Johnson said. The organization also had a website called arthousekentucky.org to highlight artists’ work. “It’s an opportunity for Kentucky artists to sell their work to a worldwide community,” Johnson said. “So we help those artists put their work on the website and then we promote those pieces via our social media pages and other in other ways.”

The e-commerce efforts had already been in the works, but COVID-19 spurred them on, Johnson said. “It really kind of expedited that for us to help artists in one way or another,” he said. “When we first started, about 40% of our artists had some type of online e-commerce capability. And now that number is about 90%. The vast majority of our artists are selling somehow online.”

In addition, Community Ventures shifted its educational workshops online, through platforms like Teams and Zoom. “We would have gotten there eventually, but COVID kind of expedited that opportunity for us,” he said.

Negotiating content with community partners in Poughkeepsie

Besides adjusting to COVID-19-related constraints, adaptation also meant adjusting due to censorship, as was the case with a project spearheaded by Hudson River Housing and Arts Mid-Hudson. For their NeighborWorks Cohort initiative, the two organizations ran into resistance with a partnering business who felt the public art installation slated for its space to be too controversial.

“It was too much in their face, and they declined to exhibit it,” said Anita Kiewra, a care manager with Hudson River Housing.

The installation piece, by a Mexican American artist named Isabel Velasco Gómez, was one of a number of placemaking projects meant to amplify underrepresented voices and artists. The idea, as developed through the cohort process, was to build strength in the community and prevent displacement.

Velasco Gómez, who has skills as a piñata maker in addition to her background in painting and textile art, has lived in Poughkeepsie for the past 17 years, and first became involved with Hudson River Housing back in 2018 after meeting Kiewra through church.

Kiewra said she was teaching Latin American Art in a summer program, and realized she needed to collaborate with artists that were experts in the culture based on their lived experience and practice. “Rather than do research for my American version, I decided to meet some folks in our community and reach out to first generation Latin American people,” Kiewra said.

Over the course of that summer, Velasco Gómez worked with the young people to make seven pinatas using traditional Mexican design and materials, and since then, has worked with Kiewra on a variety of workshops. This year, she was chosen as one of the artists to engage the community through the projects sponsored by Hudson River Housing and Arts Mid-Hudson.

Velasco Gómez envisioned a giant papier-mâché sculpture that spoke to the plight of children detained in ICE facilities at the border.

“Basically it looks like two children wrapped in a cage,” Velasco Gómez says of the sculpture. “They don’t understand why they are separated.” In her work, Velasco Gómez employs cardboard to create the structure for her piñatas. For this piece, she used bamboo for the cages. The other part included a giant Statue of Liberty, also made of papier-mâché.

Velasco Gómez wanted to bring attention to the plight of immigrants at the border, but it was more than that. “I was thinking the other day when I was doing my work, that with the pandemic going on, everyone is locked up in some way,” she said. “Everybody has to remain at home. We as a people—we are experiencing depression, we are distressed. I was thinking in that moment, how these children must be feeling. We can all go to our houses. Those children are not able to go anywhere.”

Originally, the work was going to be shown at a business which had previously offered up space for artists to exhibit work, according to Kiewra. “The political nature of the exhibit was the reason for not accepting Isabel’s work. They viewed it as too political,” she said.

Arts Mid-Hudson and Hudson River Housing ultimately found a different exhibition space, a nonprofit dedicated to Latino issues. It’s smaller than the originally proposed space at the other business, which meant that Velasco Gómez had to adjust her vision for the work.

The move speaks to the many ways that placemaking projects, by their public nature, need to be adaptable. For the border separation installation, Arts Mid-Hudson and Hudson River Housing found that finding the right presenting partner was key in making the public sculpture come to life.

With so many stakeholders at play, a project needs to be able to shift in process. Neighbors, community leaders, businesses, artists and organizers all have to work together and get on board with each other in order to make things happen. And if there’s an issue, it’s up to the project designers to figure out what adjustments can be made in order to carry out the vision of the project in a way that serves the community.

Key Takeaways

- Having partnerships in place before a crisis hits allows for greater resiliency and brings community voice into those resiliency efforts.

- Placekeeping projects need to be adaptable to quickly change to current environments.

- Balancing multiple stakeholder goals and needs also requires flexibility.

- The challenges of moving to a digital space also offer opportunities for increased access, engagement, and documentation of work.

Header photo: Isabel Velsaco Gomez (right) displays her sculptures in a Poughkeepsie business.