Baltimore gallerist and fashion historian Joy Davis on Black spaces and Black stories

Joy Davis attributes her love of “old stuff” to her father, who worked as an antique buyer in the Baltimore area when she was growing up.

“Through him I learned the value of material culture, but at the time it was the value of ‘stuff’,” she says. “I found an appreciation for old stuff, and telling stories about old stuff, and doing research on old stuff.”

Later, as a teen going to punk shows in people’s houses, she came to understand the value of creating spaces for people, though she didn’t have the language for it at the time.

“I was just thinking about creating space and how punk brings people together, realizing why going to punk shows was important to people like me even though I didn’t see all the people I wanted to see there, like my queer friends and Black friends.”

These early life experiences, those things a person doesn’t usually think too hard on at the time but just accepts as a part of life, directly inform what Davis is doing now. The punk rock daughter of an antique buyer went on to study African American and diasporic art, fashion history, and colonial dress at the Fashion Institute of Technology, as well as museum practice and curatorial and conservation studies.

“Learning I could go to school for fashion history and museum studies and learning how to navigate the world through museums was new to me,” she says. “I didn’t know there was a place to do that job until I was 22 years old and [finishing my undergraduate degree]. It was a Hail Mary: ‘I can do this; all hope isn’t lost!'”

She otherwise would have ended up becoming an underwater archaeologist…life can take some strange turns sometimes.

After finishing her graduate coursework at FIT, Davis held a series of job in the field of archival fashion, first in museums and then in the private sector.

“There were a lot NDAs, pomp and circumstance, and politics, but also better paychecks and benefits,” she laughs.

Towards the end of her corporate career she started saving money to open her own gallery. She wanted to open one in New York City, where she was living at the time, but, for a number of reasons (the cost of rent, competition, her relative newness to the field), that didn’t seem practical or feasible. So she decided to move back to Maryland and open Waller Gallery on the ground floor of her home in Baltimore, where really nothing like it existed, rather than in New York where her gallery would have been just another Black-owned space among…well, more than “none,” anyway.

Waller Gallery supports artists and scholars of color through collecting, exhibitions, programming, and collaborative projects. The gallery considers all forms of art, such as design, social practice, craft, and digital art, from artists at any stage in their practice, including incoming and reentering artists, those who haven’t practiced or shown in awhile, and those switching mediums—circumstances under which it can be difficult for an artist to book a show.

Davis spent two years working on her vision for Waller Gallery before it opened in April 2017. Much of her vision for the space was shaped by conversations she had with other artists coming out of art school “and their terrible, shitty experiences,” as well as talking to gallerists who were friendly and transparent enough to speak with her (the gallery world is notoriously private and secretive).

“It was really polling a bunch of people I knew about their experiences,” she explains. “I’m still building on that research that I did and trying to figure out ways I can apply that to the space.”

One of the biggest ideas that helped her inform the space, she says, was that a space be created at all.

“The need alone for a space for Black artists to show work was the first thing,” she says, “and to show it frequently and have the chance to spend time around Black art not for the white gaze, and provide mentorship to guide the artists through their art work without the white gaze.” She heard from Black artists again and again that if their art wasn’t centered around “Blackness,” it was either overly critiqued or treated as not being valid.

“A white person doesn’t have to surround the ethos of their work around being white,” she explains. “We would probably look down on it if they did. But the way a Black person has to talk [about their art] is creating Black and brown people as monoliths in art spaces. It’s problematic.”

Waller Gallery is still fairly new, and initially Davis was still working a full-time job as she also juggled the roles of director and curator. As it is about to enter its third year, Davis is looking into additional funding sources and working on grants so she can pay interns and give artists a stipend for coming into the space.

“Oftentimes there is a very deliberate misuse of Black and brown art in spaces where those artists don’t get a stipend but white artists do, [or the white artists have more resources available to them],” says David. “We’re trying to find ways to be more equitable in our space and put our money where our mouth is.”

Galleries handle things a lot differently than museums. In Davis’s experience in the museum world, the museum model isn’t solely just about making money; there’s also an educational component, which she feels is important to also include in the gallery.

“We inject that into our space. I feel confident to do that. I think it’s very necessary to educate the person coming into the space about the artwork on display,” she states.

The education component at Waller Gallery takes on the form of a variety of after-school programs with school-aged kids, college students in curatorial exhibition design and art administration programs, and workshops covering everything from zine-making to fermentation. Davis would like to build up the education programming even more to be able to have a regular weekly time for students to come in.

She would also like to expand the programming to also include support for artist talks, artist panels, and scholarly panels on topics that are important to the artists and also to the community, which could include bringing speakers in from out of town and covering their travel expenses while also keeping everything free for their audience. As it stands right now, she says, they’re looking at models to charge a small fee for some of these events in order to stay sustainable and support themselves.

Waller Gallery’s 2020 calendar is already full, and Davis is especially excited to be collaborating with Lauwer gallery in the Netherlands on a bit of a cross-cultural art exchange show with the working title “Form and Function.” This show will be about fashion, the body, and the presentation of the body. The Netherlands portion will feature prints from two or three of Waller’s artists, and Davis says she hopes Waller will be able to show some sculpture work from a couple of Lauwer’s artists.

“It’s part of our mission to collaborate and get our artists showing outside of our space, outside of our city and region, and outside of the country if we can. We’ve done collaborations before in the city and that’s been great, but we want to push more beyond that.”

As she explores different options for additional funding, Davis hopes to be able to have enough funds to start bringing artists in from other countries and also send the artists she works with to other countries. She’s also looking to get into publishing, starting with a catalogue of the work that will be exhibited in the Waller-Lauwer “Form and Function” show—any opportunity to further promote their artists, she says.

It seems only fitting that the Waller-Lauwer show is focused on fashion and the body, a subject that has been near and dear in Davis’s life since childhood, when going to estate sales with her dad got her thinking more deeply about the clothes she was wearing beyond just thinking they were pretty.

At FIT, she was acutely aware of being a Black person in a mostly white space, so she mostly just focused on doing her work and “getting a good enough grade to go to the next class.”

“It really helped my work ethic to work in the fields that I did, but it started from a not-so-lovely place of just trying survive in the program,” she recalls.

While she was still in school, her friend Dana Goodin, a textile conservator, approached her about starting a fashion podcast. At the time she wasn’t interested—”my head was down just trying to finish school”—but a couple of years later, her other friend and fashion scholar Jasmine Helm approached her again about joining them in the Unravel podcast, a show that seeks to educate the public about the importance of fashion in history and daily life. Davis joined the podcast in its second year and “hit the ground running.”

Her field of specialization in fashion history deals with the material culture of Black and brown subjects and Black diaspora. She remembers being excited when she found out she could focus her studies on these subjects in school and didn’t have to do all her research on white people. As of today, there are only about 50 scholars around the world in this field of expertise, and, much like many other niche fields of study focused on the African continent, it still tends to be dominated by white people.

“Black people just didn’t have access to those things,” she says simply, noting that white people historically have had more access to the particular schools that offer these kinds of specialty programs, as well as access to the resources that enable to them travel for their research.

Davis heavily incorporates her research into the podcast, prioritizing Black and brown histories as well as lesser-known white histories (rather than the histories that have already been thoroughly documented because of the robust amount of archival material readily available).

“My historical research and the podcast really do work in tandem,” she says. “All of the research I’ve done has been on the podcast in some way. It really is a way to work on kinks in the research or talk about stuff I wouldn’t be able to touch on or capture in a book or paper.”

As Davis describes it, the podcast seeks to democratize and decentralize the higher education that each of its hosts—Davis, Goodin, and Helm—received at FIT.

“We really felt our program was one of the best for learning about fashion history,” Davis explains. “We wanted to share that information. You shouldn’t have to sit for a two-year degree [to have access to this knowledge]. We’re trying to give you an education for free. We also thought we can inform people in a fun way that’s related to contemporary ideas.”

They also bring in guest scholars who are experts in their respective fields to give a diversity of perspectives, from high-profile scholars who have received a lot of national press to independent scholars and professors at smaller institutions.

One of the most awesome things to come out of the podcast, Davis says, is that the content they have produced on Unravel is now being included on school syllabi across the country, which means their research is being used to teach the next generation of scholars in their fields. While that may not have been the original intention, it’s certainly in keeping with the podcast’s goal, as well as Davis’s personal mission, to educate the public.

Despite her different career “hats”—fashion history scholar and podcast host; contemporary art gallery owner and entrepreneur—everything Davis is doing today is the result of interests that took early root, and, in an odd way, seem to be quite a natural progression for the punk rock daughter of an antique buyer in Baltimore. It’s good that that whole underwater archaeologist thing didn’t work out, after all.

Joy Davis is a Salzburg Global Fellow, part of the 2019 cohort of the Salzburg Global Forum for Young Cultural Innovators. Springboard for the Arts Associate Director Carl Atiya Swanson is also a Fellow, read his reflections on the Young Cultural Innovators Forum.

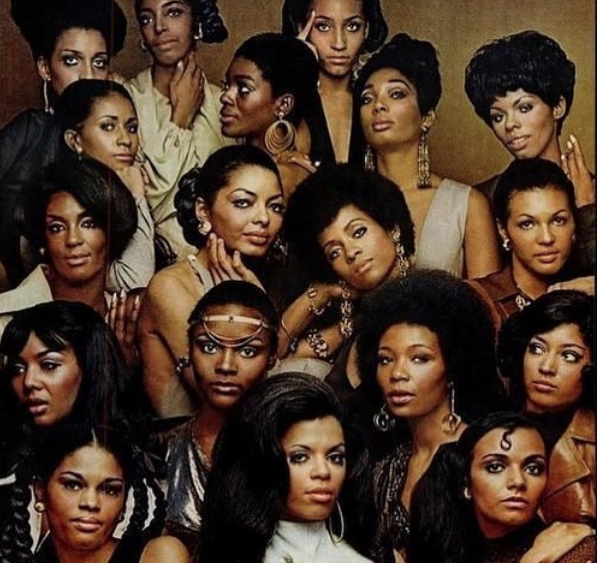

All photos courtesy of Joy Davis, the Waller Gallery on Facebook, and the Unravel podcast on Instagram.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

Vastly and as often as possible. It’s built into our mission.

(2) How do you start a project?

I start a project with a concept first, or with the title. Either way I’ve learned over the years not to overthink that part because if I do, I’ll never start. There’s usually a very vivid concept or title, then I work from there.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

We provide a cultural service to the community that we will continually strengthen and grow through our Waller Projects that encompasses artist talks, workshops, cultural exchanges, and events centered around community’s interests. My knowledge from my respective fields has created many opportunities for our interns in the internship program for them to grow their skills as art administrators. The ability to grow and adapt are skills we value. These are values we want to use to support our Baltimore community and the Waller Gallery family.

(4) How do you define success?

When we have a good turnout at an event that means success for me and for the space, but also if the artist had a good experience. In our foundation we wanted to create space where they don’t feel sheltered or unsafe to create show their work, to see it to the end and see the end product. It’s such a nebulous goal and it’s hard to get feedback on it, even though it also makes me feel that we’re fulfilling the mission.

With the podcast, we average 1,500 listens a week and 2,000 per episode, so staying on top of our numbers is success. Being booked and busy is success in my scholarship; I could write a book and it would be great but if no one wants to hear me talk about it, did it really mean anything? Being booked and busy means my work has relevance, and that’s success.

(5) How do you fund your work?

My work is self-funded and funded by our community. We just opened a Patreon campaign so we will be even more dependent on the community. We have events that are paid for, and our community helps us. When someone buys artwork, it not only supports the artist but it also supports us. We’re able to break even, which I’m very proud of—that’s a hard thing to pull off. As we move forward we will be leaning more heavily on our community, and grants will help with that too. I’m also thinking of multiple revenue streams in the future, so if you ask me this question again in a year I will hope to have a lot of different answers.

Personally, the thing I get paid for the most is being the director of the gallery, doing tours and making school visits. I also get paid for being on the podcast and doing talks, like at the Textile Society of America convening in Philly. It’s interesting how you can find paid opportunities through these niche things, but becoming your own agent is a weird process.