A theatre laboratory for the New World in Akron

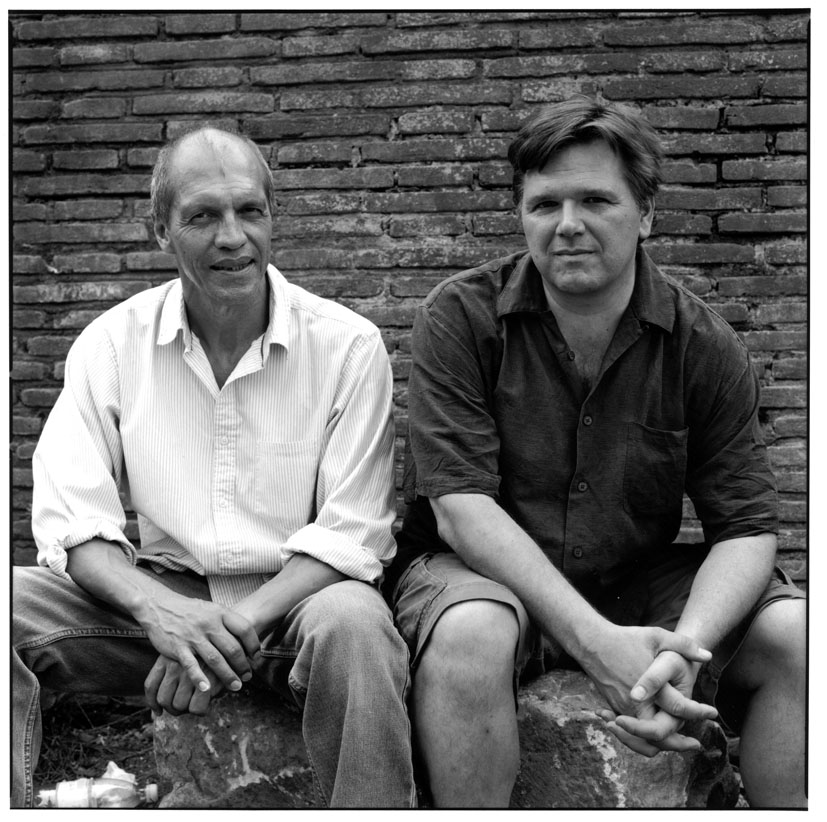

Jairo Cuesta and James Slowiak, co-founders and co-artistic directors of the New World Performance Laboratory (NWPL) in Akron, each developed their personal theatre traditions and practices under the guidance of the acclaimed Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski, whose legacy in the world of theatre is a tradition that focuses on the performers and the messages they communicate rather than any staging (he famously eliminated all props, costumes, makeup, music, and other stage dressings from his productions).

The two actually met when both were working for Grotowski in the U.S.—Slowiak, the American, and Cuesta, the Colombian, who had previously left Colombia at just 20 years old to work for Grotowski in France and later followed him to America.

When Grotowski decided to return to Europe, Cuesta felt it was time for him to follow his own pursuits after working with Grotowski for 10 years. At the same time, he also realized he was in love with Slowiak and was coming out. The two have been together for 35 years now.

After a few more years spent in Europe, Cuesta and Slowiak decided to come back to the U.S. and find a place to open their own theatre. That place ended up being Akron, Ohio.

They wanted to find a place to continue their theatre-making in the traditions of Grotowski and Konstantin Stanislavski (who developed the system for training actors from which “method acting” is derived, but whose approach was much more holistic), as well as their own tradition of extensive research around representation, multiculturalism, and inclusivity in all of their work.

They felt that, in America, the best place to do that would be in a university setting, where professors are typically free to pursue their own ideas and passions around research and there are always new kinds of students in every generation ready to embrace the most progressive social movements and ideas of the time. They knew they didn’t want to be in the more traditional commercial theatre production space, which mandates a company maintain a regular and regimented schedule of practice and performances; they wanted something better suited to their process and craft. The first university they found that was open to receiving Slowiak was the University of Akron, where he still teaches today.

From there, the “Grotowski diaspora,” as Cuesta calls the director’s global network of theatre disciples, knew the two of them had something going on out there in unassuming Akron, and soon they had a company of over a dozen young actors also interested in this tradition to found the New World Performance Laboratory. The nonprofit Center for Applied Theatre and Active Culture (CATAC) was formed later, in 2005, as an administrative umbrella for NWPL.

NWPL creates and performs their own work as well as work based on, or “in conversation with,” the works of other writers. One recent production took stories from Don Quijote that most resonated with them and mixed Spanish and English onstage without subtitles; Cuesta played Quijote and spoke mostly in Spanish, while the rest of the actors spoke mostly in English. They performed for full houses, and audiences said afterwards that they could “never not understand” what Don Quijote was saying—a testament to the communicative power of the actor and of performance that transcends language and words.

At the time of the COVID-19-related closures, NWPL had been working on a new piece called Passion’s Play, rooted in works by the Nobel Prize-winning Symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck with input from all of the members of the company all representing different cultural, religious, and political backgrounds. That is their process: to take anywhere from six months to a year to “investigate” and “gestate” a performance, which entails almost-daily investigative trainings, physical work, singing, and rehearsals with, as well as input from, all members of the company, all of whom come from “different cultural contexts,” Cuesta says.

Cuesta also teaches at Case Western Reserve University, and Slowiak still at University of Akron, so they have the chance to work with a lot of young actors, and there are also several other young theatre companies in addition to their own.

“The theater life in Akron very strong,” Cuesta says. “We have about seven small companies, which is a lot for a small city of 200,000 people. We have Broadway shows and Shakespeare companies, community theaters, and university theaters. In this kind of landscape, for five companies to be doing socio-cultural work or feminist or immigration work, it’s a nice landscape, and many of these people have come through our circle. Many of the teachers with the programs in the local high schools and universities have studied with us or done workshops with us. It’s a nice connection with the community.”

One of the company’s flagship works is The Devil’s Milk Trilogy, a series of three entirely original pieces by the company about the city of Akron and its relation to the rubber industry—rubber and tire manufacturing was the city’s primary industry for decades, and built the city’s wealth and earned it an international reputation. The Devil’s Milk series was devised in 2015 and 2016, with each play telling a different story related to Akron’s history with the rubber industry. The performance event is based loosely on John Tully’s book, The Devil’s Milk: A Social History of Rubber, along with other historical and fictional sources.

“The company was doing work about rethinking race as some kind of project, looking at race relations in the community and the city of Akron,” Cuesta explains. “Akron is the ‘Rubber Capital of the World,’ with Goodyear Tire’s headquarters here. That was the richness of Akron, because of all the factories making tires in the 1930s and ’40s created a lot of wealth. But the wealth of this city was founded in blood—the blood of cultures in South America and the Amazon jungle, the African Americans that did the more dangerous and toxic work in the factories. There is a lot of karma to clean and understand.”

The company used different techniques to develop these pieces, like the story circle techniques used in the Civil Rights Movement to collect stories from people in the community as well as people in the Amazon, who still suffer from the impact that the Amazon Rubber Boom had on their native lands.

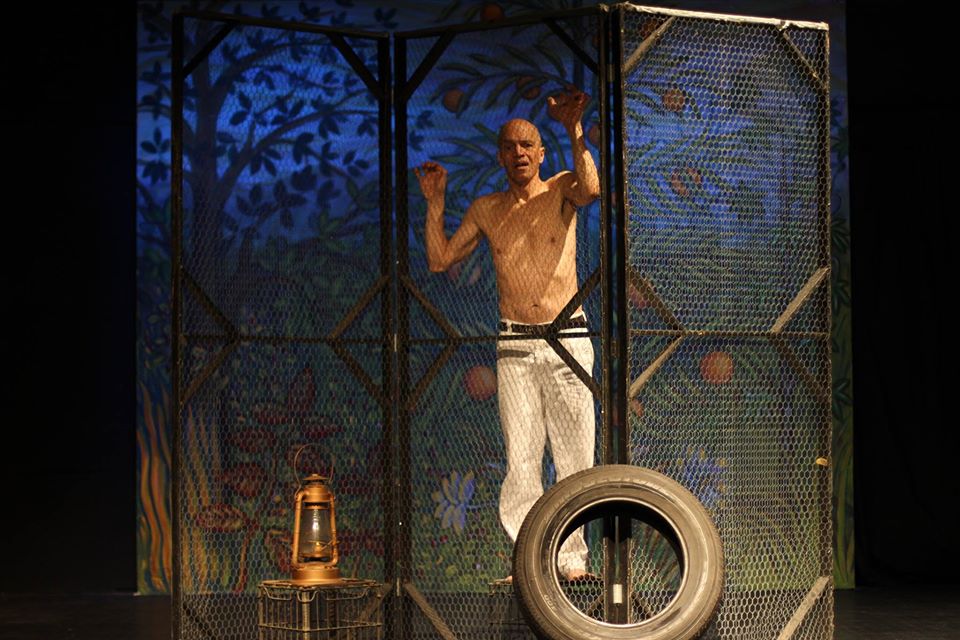

The first play in the series, Death of a Man, is a solo piece performed by Cuesta.

“I am Colombian, so stories of the Amazon are always in our imagination, and the genocide of our people from Brazilian, European, and American companies there is part of our Colombian imagination,” he says.

Death of a Man tells the story of the genocide in the 1910s in the Colombian and Peruvian Amazon through the story of one man, but one thing NWPL grappled with was whether or not they had the right to tell the story of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. Cuesta and Slowiak traveled down to the Amazon to spend time talking to and working with many of the tribal communities that had been fractured and relocated over the last century of corporate plundering of the rainforest. They also worked with anthropologists and political leaders in the area. Because the story of the Amazonian genocide is also the story of rubber, and by extension the story of Akron, the indigenous communities felt that is was appropriate for Cuesta and Slowiak to tell their story because it was also the story of their own city’s history.

“They realized it was important for the healing of the city that we told their story,” says Cuesta. He and Slowiak also traveled back to the Amazon to show them some of the rehearsals of the piece, and were extremely cognizant around the representation of whose story is it to tell and how they were telling it.

The second part of The Devil’s Milk Trilogy, Goosetown, was set in Akron in the 1910s in the German immigrant neighborhood of Goosetown, as well as inside a rubber factory. This was a rare musical production for NWPL, and the original performance featured all community actors (rather than company actors).

Part three of the trilogy, Industrial Valley, was based on reporter Ruth McKenney’s 1939 account of the formation of unions in the factories and the class and industrial conflict and strife that ensued against the backdrop of the Great Depression and the looming threat of World War II.

Each of the productions played to full houses across the city and were followed by critical discussions, during which community members would share their own memories of fathers who worked their whole lives in the factories, and so on.

“It was a very interesting moment in the community to see that [the city’s history is not just about] rich people with beautiful houses and tourist attractions, but a lot of people fighting, suffering, and dying to create new possibilities in the city,” Cuesta says. Incidentally, there is now a new monument being created for downtown Akron that will pay tribute to the thousands of workers on whose backs the rubber industry was built.

Cuesta is now working on another solo piece called Lost in Translation, an idea that started percolating for him as they were developing Don Quixote. In conversations with the company, they knew they wanted to do more to open up to the city’s Latinx community and help to make that community more visible. Cuesta himself had been moved by stories of Akron’s Latinx community, especially as the current administration took over and there were all the stories of family separation and ICE raids and anti-immigrant rhetoric everywhere in the news.

This solo performance, which he says is “a little separated from the company,” is based on stories collected from local immigrant families to engage the city’s Latinx community in a dialogue about culture, barriers, family, and displacement.

The title itself, Lost in Translation, refers to a common question that a person speaking in a non-native language will often ask: “Do you understand me?” It’s a question he has heard a lot and also asks a lot, sometimes because of a more broken language, but more often implying, “Do you really understand me?” because the deeper meaning of a particular phraseology can be lost in a translation that has no equivalent. For example, in Latin America, he says, there are many phrases that refer to being “on the other side of the river.” It is a very specific concept that has a deep meaning, but it is difficult to communicate to non-Spanish speakers.

He explains that to be “on the other side of the river” for many Latin Americans is to go somewhere else to chase your dreams or follow your path, to dream of a better life or of new opportunities and adventures. It is the “hero’s journey,” one of the most basic and common story structures throughout the history of mythology, literature, and popular culture—a person leaving a place in search of something elsewhere, or simply on a journey of self-discovery.

“That idea of ‘what made me go away, what made me cross the river’ is one of the basic elements of Lost in Translation,” he says. “The idea of ‘crossing the river’ is poetic. It’s cultural. It’s political.”

The piece is still being developed. Cuesta has had to change course a bit in conducting his interviews with the local Latinx community, especially those he was most interested in speaking with—the undocumented.

“I was very naïve thinking undocumented immigrants are going to tell me their stories now that ICE is everywhere,” he says. “It would be irresponsible to have those kinds of meetings now.” Instead, he is working with institutions that work with the local immigrants population, legal and undocumented. (Editor’s note: This conversation took place prior to COVID-19 closures and NWPL postponing their 2019-2020 season.)

With this project, he is interested in “exploring the hyphen between ‘Mexican-American’ and ‘Latin-American,'” as well as the community’s relationship to the figurative “river” as well as the actual physical river in Akron—the Cuyahoga River, which many residents view as being too contaminated to swim in—drawing a parallel to those who come from other countries where the idea of “crossing the river” has a deep cultural and spiritual meaning to them being in a new place where they are losing their physical connection to the river and to nature.

While the Knight Arts Challenge grantee Lost in Translation is not a continuation of The Devil’s Milk Trilogy, it is a certainly a thematic companion, examining the history of the city of Akron through the lenses of race, ethnicity, culture, immigration, displacement, and the environment. To stay up to date on how their latest works are progressing and for more information on the 2020-2021 season, follow NWPL on Facebook.

All photos courtesy of New World Performance Laboratory.