A rural renaissance: How small towns are leading the way in creative placemaking

In 2014, New London was the recipient of a $262,500 grant from Artplace America. The grant helped fund nine different projects. Full disclosure: I was lucky enough to be one of those recipients. We continue to enjoy the results of those projects in so many ways, not to mention on our musically imbued walks around the Mill Pond.

If you’re unfamiliar, Artplace America is a program that funds projects with the goal of creating partnerships between community development sectors and the arts and culture sector. These intersections are referred to as creative placemaking.

Artplace America recently held its 9th Annual Summit in Jackson, Mississippi. Now entering its final year, Artplace is looking to end its charter by supporting “a strong placemaking field of practitioners” and to “embed knowledge and resources within existing networks of practice and strengthen and empower local ecosystems to own and evolve the practice.”

As if to demonstrate that intent, on the last day of the their summit, Artplace shared the stage with rural culture advocate, Art of the Rural, in presenting the Rural Generation Summit 2019, thus seamlessly dovetailing from the end of one summit into the opening gathering of the next.

Rural Generation Summit 2019

The Rural Generation Summit is an event devised and organized by Art of the Rural. The goal is to bring together a cross-section of rural America with the intent of inspiring and facilitating lasting connections to rural people and places. With support from the National Endowment for the Arts and ArtPlace America. and a host of almost a dozen national networks and organizations the Summit welcomed 250 people from over 44 states and two territories to Jackson, Mississippi. This three-day gathering of the minds was a patchwork of community organizers, developers, artists, elected officials, agriculturalists, activists, educators, virtually any member of the vast societal cross-section of those who have a connection with rural places.

I was invited to attend the summit as a gatherer of media ie., photos, videos and sound recordings. My instructions were to collect enough material with which to tell a story. But for me, the story didn’t start at the summit. It happened on the way, between keynotes and outside the catered buffets. The following is a glimpse into the work being done by those who identify as “rural.”

Transformation in eight cities

Easing into a comfortable Friday afternoon departure, myself, Ashley Hanson at the wheel, (founder of Department of Public Transformation and PlaceBase Productions) and five other Minnesota artists pack into our rental van. We head south.

Our first stop is Waverly, Iowa (pop.10k) where we meet the founder of the Kohlman Park Art Walk. Jennifer Jones Ruiz was 14 years old when she organized the first Walk as a school project. The city had just put in a winding path through the park. “I guess I had a vision,” she said, “and no one discouraged me.” So she just kept doing it. She gives her dad, a lifelong potter, most of the credit for her appreciation of the arts. Now 14 years later she has 30 to 40 artists from the tri-state area come to sell their work. It’s become a staple event in the community.

Next stop: Hannibal, Missouri (pop. 17.5k) known as Mark Twain’s boyhood home. We have lunch with Michael Gaines who just celebrated 25 years as the director of the Hannibal Arts Council. He shared with us some of the trials and triumphs of feeding his town’s appetite for supporting the arts. Several times in the conversation he would say, “you never regret art.”

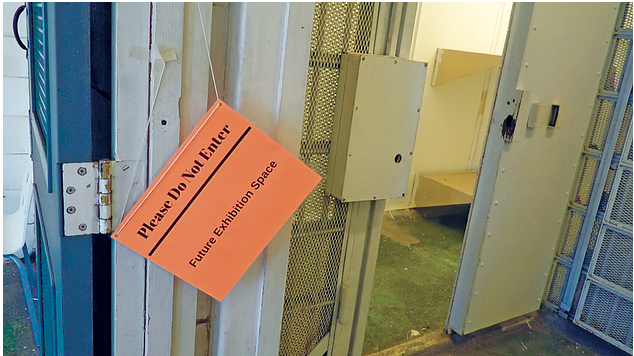

On to McComb, Mississippi (pop. 12.9k) where we visited the future site of Pike School of Art, founded by Calvin Phelps. The site is a decommissioned juvenile detention center for boys. The building is very much in transition. We tour a cellblock, gawked at the still functional surveillance system and stared silently into the two-way mirrors. When asked, how does one transform this, of all places, into a community arts place while being respectful and aware of its history, Calvin told us, upon the advice of Duluth artist Nik Nerburn, that one of his first moves was to remove the bars from the windows. He organized public arts activities in the jail and invited former inmates to attend. He sought out and consulted with others who had spent time in detention centers like this one. “Their response has been really positive,” Phelps said, “and neighbors and volunteers even helped clean the building and mow the lawn.”

The same positive energy radiated from K-12 students at the Jubilee Performing Arts Conservatory as we walked in on a class in session. Upon noticing us, the students instantly snapped into a forty-piece, fully choreographed troupe performing the Little Mermaid’s, “Kiss the Girl.” Magical. (Especially knowing that not even a year ago their initial three-story school building had collapsed just minutes after class was dismissed.)

They were now holding classes in a nearby church.

“It took us six months of kind of tiptoeing around, trying to be respectful of this place as sacred and use that energy to transform the space into the school,” explained Dr. Terrance Alexander, head of J-PAC. He beamed as he told us about their Daytime Emmy nomination, their Eddy Award for Independent Artists and how one student got a callback for the production, Hamilton.

Enjoying a tall glass of sweet tea at Sipp Cultural Center’s artist residency house in Utica, MS (pop. 878), I watched four buses unload. Summit-goers slowly made their way to the buffet tables. The house is a 1920s-era one-story home with a gorgeous wraparound porch. Sipp Culture Center is lead by Carleton Turner. Utica is his hometown. Earlier, as the opening keynote, he introduced himself to the group. Now it felt very much as if he were welcoming us into him home. Turner shared his story about finding the house and how he convinced the city to support his efforts. He spoke about his parents and grandparents and how restoration comes down to people and the land. “ The only thing that can save us is our relationship to each other and to the land,” he said. “If we are to continue to exist we must repair our connection to the places that we live. We have to adjust the way that we consume, the way we create and produce. If food is life than land is liberation. What we do with it, who controls it, who benefits from it — all are questions deeply connected to our liberation.”

That evening, driving through downtown Yazoo (pop. 27k), we ping-ponged between heartbreak and inspiration. We moved slowly down a main street where brightly painted storefronts remain adjoined to their dilapidated neighbors. As we continued on, we noticed something that made us stop the van and shift into reverse. Deep between the rubble we spied a makeshift outdoor theater. The words “God’s Flower Garden” were painted on an exposed beam. “Oh, good job ya’ll” praised Rural Generation Summit Director of Programs Savannah Barrett, thanking whoever it was who cleared that rubble, made a stage and brought in benches.

That evening, driving through downtown Yazoo (pop. 27k), we ping-ponged between heartbreak and inspiration. We moved slowly down a main street where brightly painted storefronts remain adjoined to their dilapidated neighbors. As we continued on, we noticed something that made us stop the van and shift into reverse. Deep between the rubble we spied a makeshift outdoor theater. The words “God’s Flower Garden” were painted on an exposed beam. “Oh, good job ya’ll” praised Rural Generation Summit Director of Programs Savannah Barrett, thanking whoever it was who cleared that rubble, made a stage and brought in benches.

According to her website, Barrett was raised on a seventh-generation homeplace in Grayson Springs, Kentucky and resides in Louisville. Among a host of other impressive projects, Barrett co-leads the Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange with a cast of artists and community builders throughout the state to innovate on a regional creative placemaking strategy. When asked what she sees as the most significant issues impacting the field of rural creative placemaking, perception – both external and internal – comes to mind.

“It takes self determination, and being able to tell your own story and speak yourself into existence – and then to speak your community into existence,” she said. “You have to be doing that individual one-on-one local work at the same time as building connections outside of it [in order to] build the change, we want to see.”

It’s worth mentioning that this interview took place in the staff room of the BB King Museum in Indianola, with Barrett sitting alongside Minnesota arts leader, Vickie Benson. Benson has been the Arts Program Director for the McKnight Foundation for the last 11 years and will soon be retiring. Both women exude grace and thoughtfulness. It’s immediately apparent that they hold deep respect for one another.

It’s worth mentioning that this interview took place in the staff room of the BB King Museum in Indianola, with Barrett sitting alongside Minnesota arts leader, Vickie Benson. Benson has been the Arts Program Director for the McKnight Foundation for the last 11 years and will soon be retiring. Both women exude grace and thoughtfulness. It’s immediately apparent that they hold deep respect for one another.

The elder, Benson, explains, “we’re kindred spirits – we think we lived other lives together.”

Barrett went on to say, “I think if we could just give rural kids the gift of fluidity, let them know that it’s okay to go. And that they have something to come back to and to contribute to that’s important. Someone said this morning, so often for us to value our own culture it has to be repackaged and sent back to us. So for the BB King Museum to be here, in Indianola, in his home town, for people who are growing up learning how to play blues music and roots music in their living room and on their porch with the elders in their family — for them to know that they can walk down the street and see the BB King museum and see how much it means to the rest of the world — that’s transformative power.”

We asked them both tell us something about their places. Barrett spoke about Kentucky. “We’re a state full of cave systems, which means the water that connects us all is moving underfoot all the time. So if you’re in Harlan County, or Fulton County, or local or Lexington wherever you are you connected by water. And we all live downstream. So we better treat each other well.”

Benson paused for a moment. In the room are two Minnesotans (myself included) and two Kentuckians. Of Minnesota, she said this: “There’s a beauty that words don’t really express in Minnesota. In the rural aspects of Minnesota, the roads that are beckoning us to either walk down or drive down and experience the lushness of nature. And the excitement of people living their lives, being excited about what’s happening in their communities. And there’s a quiet resolve and kindness. And I say quiet. Because we’re North. We’re northern people. So, we dance but it’s a little more quiet than what happens in Mississippi, but it’s wonderful.”

It was time to go home. My own community group’s fundraiser was knee-deep in a hog roasting rummage sale. On the flight I take a moment to add it up: eight towns, dozens of buildings, homes, and whole streets being transformed into places that facilitate connection through storytelling, food and land. Here was proof of the power of creative placemaking; proof that rural places are finding solidarity in this endeavor.

“If the future of our country relies on common ground, rural America and Indian Country will lead the way. We hope to meet you there.” – Art of the Rural.

This post originally appeared on Bethany Lacktorin’s website “My Ocean” here.