Talon Bazille Raps, Performs, Records, Builds and Shares

The Rural Regenerator Fellowship brings together individual artists, makers, and culture bearers, grassroots organizers, community development workers, public sector workers and other rural change-makers who are committed to advancing the role of art, culture and creativity in rural development and community building. In 2022, we asked a collective of local writers to sit down with current Rural Regenerator cohort members to share more about their work.

The first time I heard Talon Bazille, I was hurtling down a dusty country highway, my two young kids squabbling loudly in the backseat. It was late 2020, and South Dakota Public Radio’s Lori Walsh was interviewing him about the release of his then latest hip-hop creation,Traveling the Multiverse with Iktomi, a 29 song, three-part epic, that included collaborations with over a dozen other emerging and established artists. “Shhhhhh!” I said to the kids, turning up the volume, impressed by the immensity of the undertaking. Even the kids got quiet as the music started, lulled by the rhythm and flow of the song.

The music ended and at the bequest of Walsh, Bazille started talking about his community recording studio, where he offered free recording sessions to pretty much anyone who wanted to give it a try. “How can one person be doing all this?” I thought to myself as the rest of the interview was lost to the rising din from the backseat.

Soon after, I came across Bazille in a livestreamed conversation broadcast by the Cave Collective, a non-profit performance venue in Rapid City. Again, I was astonished by the volume of work he was generating, but this time, minus the distractions, I was equally amazed by his generosity of spirit. He spoke candidly about his struggles as a younger man with depression, generational trauma, and grief, and wove the story of his pain with strength, vulnerability, and grace in a combination I’ve never encountered before. His stories provided no solutions – it clearly was not his intention to create a false sense of security for his listeners – and yet it was impossible not to be warmed by the glow of his expansive humanity.

Soon after, I came across Bazille in a livestreamed conversation broadcast by the Cave Collective, a non-profit performance venue in Rapid City. Again, I was astonished by the volume of work he was generating, but this time, minus the distractions, I was equally amazed by his generosity of spirit. He spoke candidly about his struggles as a younger man with depression, generational trauma, and grief, and wove the story of his pain with strength, vulnerability, and grace in a combination I’ve never encountered before. His stories provided no solutions – it clearly was not his intention to create a false sense of security for his listeners – and yet it was impossible not to be warmed by the glow of his expansive humanity.

If you Google Talon Bazille, you will find publications and organizations from the University of Pennsylvania to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts to the Kennedy Center lauding his work. “Talon brings so much generosity and support to the table in everything he does.” says Peter Strong, one of the directors of Racing Magpie, a Lakota-centric arts and culture organization. “From solo performances that scorched national audience (the ‘Love Fight Pray’ event with the Kennedy Center) to collaborative efforts with grassroots artists, he has brought thoughtfulness and creativity…The first I ever heard about Talon was his incredible generosity in opening up his recording studio to a wide variety of Native artists and giving and giving of his time and equipment and expertise and encouragement to his community.”

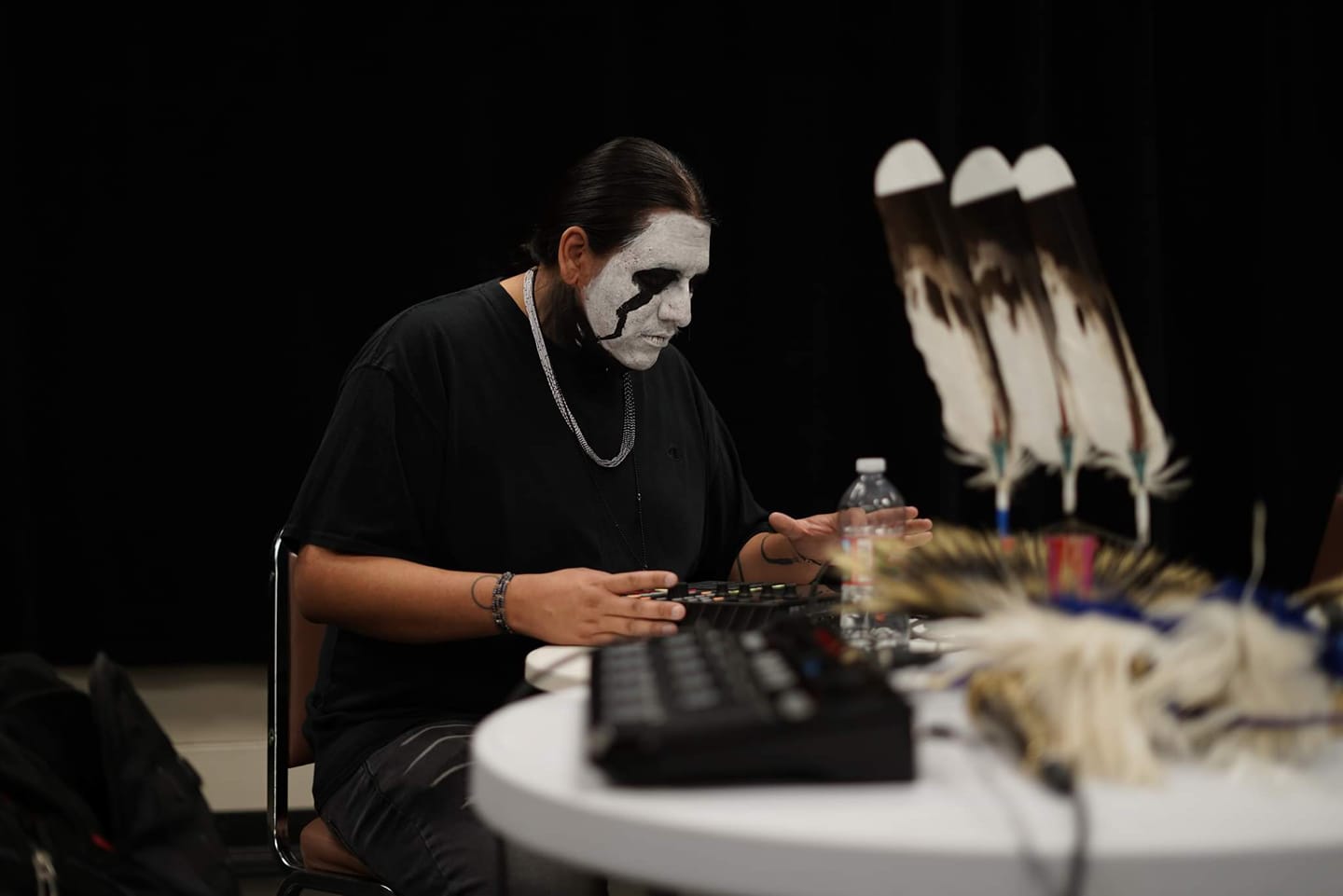

Bazille is humble about these accomplishments, but not self-deprecating. Ask him how he would describe himself and he has a three-prong mission statement at the ready. He’s a man who speaks in paragraphs, not sentences, and his self-awareness is as riveting as his humility is disarming. He speaks about the Dakota aesthetic he learned from Oscar Howe: the practice of “becoming nothingness,” of knowing your power but releasing your ego, of being prayerful in all you create, and it’s clear he is exceptionally good at practicing what he preaches.

So what’s the three-prong approach that currently defines his work? Prong One: Hip-hop artist who expresses himself verbally and also seeks to uplift his life and cultural traditions as an artist with Lakota/Dakota heritage. Prong Two: Studio manager, in charge of recording, mixing, consulting for his community recording studio Wonahun Was’te’ Studios/Records, which in Lakota means “bringing good things through the healing sounds of songs.” Prong Three: Producer and sound designer, his newest pursuit, for museums and theater, as well as private sessions online.

First Inspiration

Bazille was always attracted to hip-hop. He appreciated the genre’s creative flexibility. Lines could be long or short, ideas weren’t confined to stanza length. And it was accessible – it was music you could make without a band. Perhaps most importantly, as a kid on the reservation he was seeing members of his community rapping and making an impact with their work.

One of these early influences was Maniac the SiouxperNatural, a rapper from Bazille’s hometown of Eagle Butte, SD. “In his album Nightmerika, I could see my home reflected and I thought ‘I want to represent my world like that.’” he says. When Bazille approached his hero, Maniac encouraged him, eventually even gave him his first mic, and it’s what he used to record his first two albums.

Bazille was already deep into his journey with hip-hop before leaving South Dakota to attend college at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, but he hadn’t planned to continue as a rapper there. He did, however, get involved with the student radio station, gleefully sharing Native artists from home while also studying psychology.

He found his way back to making his own music though, performing on the East Coast before returning to South Dakota. He describes his albums as “like a salad bar. You can take what you want. I don’t expect everybody to like everything.”

That’s intentional. “I’m not an activist rapper,” he emphasizes. “In my opinion, hip-hop is not an agreeable genre. It’s like comedy. Half the people should ‘get it,’ and half should be freaked out. That’s why my DAPL [Dakota Access Pipeline] songs are free, because it is too easy for people to agree with them”

Wonahun Was’te’

Bazille’s community recording studio started out with a simple setup in a car. Low overheard (literally and figuratively) and mobility, gave him the flexibility to build on a foundation of openness. He’d set up his gear and invite friends and community members to record for free. “I wanted to overcome the scarcity mindset,” he says. “A free studio instigates the mentality that we share knowledge.”

“I’ve been recording since 2007,” he says. “The studio is a way to share that knowledge.” He’s accumulated a nuanced skill set from his years on the scene and wants to help other artists and creatives manifest their own dreams by offering the tools to take their work to the next level. “I want them to feel empowered to do this themselves,” he says. He doesn’t care if it puts him out of business. He believes encouraging a community that supports altruism is the path to regeneration, and he is not afraid to put this theory to the test.

The milestones he looks to now are about building relationships. He hopes to continue to build community in the Midwest that gives people the opportunity to find out , as he says, “that the process is actually the pay-off.”

“I am nobody means I am ready for anything”

Bazille’s latest album, Taku Sni, released this past March, is cinematic and sweeping, a collage of words and rhythms with samples from movies and other audio sources that all have a Native connection, using them was “a reappropriation,” he says. Through these soundscapes, Bazille’s lyrics wind like a dark strip of highway. It’s easy to imagine the years he spent recording in his car when you listen, the vast plains of West River Dakota spread out before you, the horizon always exactly the same distance from your windshield, no matter how many miles you cover.

From the start, Bazille sets a marathon runner’s pace, though it’s clear there’s no finish line for this journey. Thematically, the album follows the philosophy Bazille got from Howe: ‘I am no one,’ and that ethos reverberates through the songs. In every track you hear it and feel it – the power rooted in an honesty that is at turns brutal and then tender, the power that comes from being so true to oneself the self fades into an expanse of weathered grass and deep roots.

From the start, Bazille sets a marathon runner’s pace, though it’s clear there’s no finish line for this journey. Thematically, the album follows the philosophy Bazille got from Howe: ‘I am no one,’ and that ethos reverberates through the songs. In every track you hear it and feel it – the power rooted in an honesty that is at turns brutal and then tender, the power that comes from being so true to oneself the self fades into an expanse of weathered grass and deep roots.

Only thing I need is this

They call me pitiful when readin’ scripts,

I just see this as the greatest story ever lived

Abide by the code

Mobs could get inside. In like-minded, I’ve

Controlled

My soul to count coup on an ivy-league

If you see fatigue, stay intrigued

Because this ain’t make-believe or

Maybelline

I’m made up from a greater-thing

Even in a simulation-reservation making

Dreams

Taku Sni miye’

By the end of the album I think I’m beginning to understand a little bit: Being no one means being everyone.

There’s a lot on the docket for Bazille. This summer he will present a collaboration with fellow rapper Supaman as part of We The Peoples Before, a celebration of 25 years of the First Peoples Fund at the Kennedy Center. He’s also been invited to contribute to an Oscar Howe tribute among other things.

But when you ask him about his goals, they are all about uplifting his community whenever possible. Going forward, he is being very intentional about working with Native artists in other genres such as Witko at Trap Tipi, Oglala Lakota visual artist Ray Janis, and Sicangu Lakota artist Tani Gordon. There’s also lots of video collaborations in the works and a project with Crow Creek Dakota artist Bobby J at Wonahun Was’te as well. “I just want to keep feeding this economy of Native artists,” he says.