Annie Hough Creates Characters to Make the Truth Bearable

The Rural Regenerator Fellowship brings together individual artists, makers, and culture bearers, grassroots organizers, community development workers, public sector workers and other rural change-makers who are committed to advancing the role of art, culture and creativity in rural development and community building. In 2022, we asked a collective of local writers to sit down with current Rural Regenerator cohort members to share more about their work.

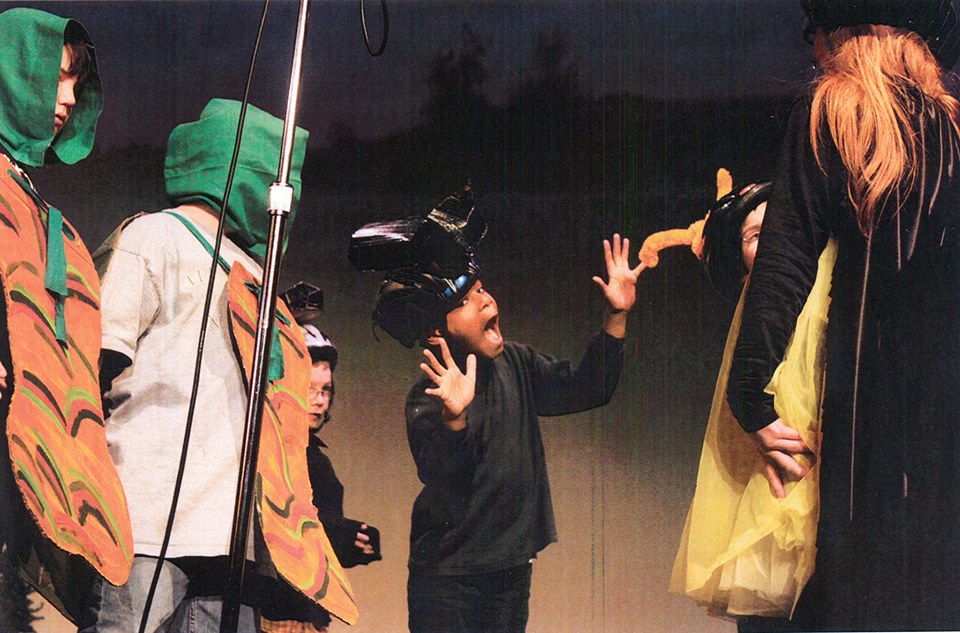

Playwright Annie Hough finds her way to her characters through research, but once she meets them, they take on a life of their own. “The frog in Meadow Adventures I thought was going to be a major character but he ended up never saying a word,” she says about one of her recent productions.

This mirrors Hough’s own unexpected entry into playwriting. She was in graduate school for horticulture when she won a grant from an agency for artists with disabilities to take a playwriting class. She wrote her first play then. It was well-received and ended up being produced at a few festivals. “That gave me the crazy idea that I’d like to write a play for the final project at University of Minnesota,’ she told Ladyboss Midwest recently, “I had to jump through some hoops to get it done, but it was really fun.”

The play was about an apple maggot, a not-so-unusual character for Hough, and was eventually produced in Hough’s hometown of Detroit Lakes, (“My first big break!” Hough jokes) by Amy Stearns at the Historic Holmes Theatre. “She [Stearns] wanted to promote local talent because she wanted her kids to see they could succeed as artists in a small town.” The play proved Stearns right and marked a turning point: Hough had found her calling and her creative voice.

Hough’s background in horticulture has been a huge inspiration for her work. “I love introducing people to ecosystems,” she says. “I love reading and researching about them. I follow my curiosity, and then the characters speak for themselves.” Animals, plants, and especially insects, all share the stage, bringing Hough’s careful research to life.

This dovetails with one Hough’s biggest goals as a playwright. Many of her plays include intergenerational relationships in addition to interspecies relationships. These artistic choices serve an intentional dual purpose: the narrative represents an awakening to the environment that surrounds the characters, often in the form of a younger character guided by an older one, while the production itself literally brings people of all ages together to experience the same awakening – not only in the audience, but in the cast as well.

Many productions and readings of Hough’s plays have been in rural areas or small towns. Hough sees rural celebration as a form of regeneration, as well as celebrating the ecosystems present in rural locations. By deepening the relationships people have with the places they live, her plays actively create stronger human communities, but also stronger connections to the creatures and plants that occupy the same geography.

Scene from Wetland Adventures

This ethos is reflected in other early supporters of Hough’s plays, including Kelly Blackledge, the US Wildlife Service Park Ranger at Tamarac Wildlife Refuge in Rochert, a small community in northern Minnesota. “Annie Hough’s work has been a treasure that compliments the environmental education at [the refuge.] Hough’s plays bring ecosystems and conservation messages to youth and families in a non-traditional way. This unique means of education through theater helps us reach new audiences and further extend our goal of growing stewards for natural resources,” says Blackledge.

Other recent collaborators include director Jacob Hartje at Theatre B, and Hough says Tania Blanich at The Arts Partnership has been wonderful at providing feedback on grant proposals. “My family and friends are also extremely supportive of my work. They attend my plays and help with tech things and give feedback on grant stuff. Yet I ALWAYS forget to mention them in interviews! Last summer, my friend Richard and our dog Elmer, my dad and his wife, my siblings and their families attended the play in Woodlawn Park,” she says.

When I ask if it is hard to let go of creative control after she’s completed a play, she replies, laughing, “No! One of my favorite parts [of writing plays] is turning over the work to other people so they can use their gifts to bring the work to life!” For Hough, the production itself is an opportunity to build community.

Hough suffered a traumatic brain injury when she was in her teens, but until recently, she had only ever written a character with disabilities for the project she created in graduate school. “It was really painful for me to be a kid with disabilities and never see myself in movies or plays or even books. A friend of mine asked, ‘Why don’t you use disabled characters?’ And it dawned on me, it was because it was so painful. I realized I could empower kids who are disabled by using characters that are disabled. I can’t believe it took me until my seventh play to realize.”

Writing a character with disabilities turned out to be easy, but not simply because she lives with a disability. When she is writing her human characters she taps into her own childhood memories. Memories of being left out, of being ignored, of being treated differently, but also the joy and wonder of the world when all is new. “I try to speak honestly and candidly from a place of innocence without agenda,” she says, and that allows her characters to do the same.

Visibility matters, but just as Hough’s disability doesn’t define her, it doesn’t define her characters either. Hough’s most recent play features a young girl, Lucille, newly in a wheelchair after a terrible car accident where she also loses her mother. While the play spends a little time investigating this new reality for Lucille, giving her a chance to share her story, the bulk of the dialogue occurs between creatures living in and around the wheel chair accessible raised bed gardens that Lucille’s grandmother has had built to accommodate Lucille’s summer-long visit. The conversations between these characters are as light and airy as the creatures themselves (most of whom are insects) but the breezy nature of the dialogue belies a deeper, more fertile narrative about death and transformation.

“I try not to be too preachy.” Hough tells me when I ask about these themes in her work. “My favorite characters are the ones that start out a bit villainous but by the end are loveable.”

A common conundrum for artists creating work for a young audience is how honest to be about the difficult realities of life. Put another way: Is it the artist’s job to tell them the truth or preserve their innocence? The children’s writer Kate DiCamillo answers that question with another question: “How do we tell the truth and make the truth bearable?” DiCamillo goes on to answer the question by saying: “I think our job is to love the world.” Hough unmistakably pursues this in her plays as well. It is impossible to miss her passion for nature and relationships between all the many denizens represented therein. The small inhabitants of the worlds she creates are nuanced and detailed, “educational” but not in a dry, textbook way. They fall into and out of love with each other, they change, they grow, they face their own mortality recklessly, but admirably. And in this way teach the audience not only about the worlds that surround and include us, but also about our own humanity.

“Some arthropods have such brief lifespans. They really can’t waste time.” Hough explains. Which depending on how you look at it, might also be said of us humans.

The last year has been fruitful creatively for Hough. A recent move from Fargo, North Dakota to Moorhead, Minnesota sparked new connections and opportunities. Hough is especially thrilled with the community created by the Rural Regenerators Fellowship, as well as a recent career development grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board.

“After a lot of years of struggle, it feels like things are really falling into place now.” she says. “The support is helping me relax and enjoy life more, and to take success as it comes. It’s getting easier to trust that things will come together.” She also adds “I am an introvert so I was nervous to meet the other Fellows but they all are so cool and seem to think I am cool too. I got to talk about my plays and everyone has been really interested. It’s been wonderful to talk about my work with other artists.”

Looking forward, Hough is excited to keep writing plays and building community. And she’s really excited for gardening season. She laughs, “I’ve got my own garden this year, and I can’t wait to work in it. It will be first hand research for future plays!”