Renewable energy art helps us design a better future

The planet is getting warmer. Sea levels are rising. Climate change is being felt in disasters and shifting ecosystems around the world, in a way that’s often disturbing to individuals wondering how they can help.

In this time of uncertainty, artists can play a valuable role. Climate change requires rethinking our environments and lifestyles — and artists and designers have the skills to do so in a way that’s imaginative, inviting, and people-centered.

That’s the idea behind the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), an organization that promotes the intersection of public art with sustainable energy infrastructure.

LAGI was founded in Dubai in 2008, and is now based in Pittsburgh under the umbrella of a nonprofit, the Society for Cultural Exchange. In 2010, LAGI launched an international competition, inviting proposals for installations that serve doubly as public art and as renewable energy sources.

“The intention is to change the conversation around climate change from one that focuses on the quite real, scary aspects to one that is more positive, that allows people to be inspired about the beauty of our post-carbon future,” says Robert Ferry, one of LAGI’s founding directors alongside Elizabeth Monoian.

“Some of the negative messages [about climate change] have the effect of turning people off, because they feel overwhelmed by the intractability of the problem,” Ferry says.

The installations prototyped through LAGI are both symbolic and practical: They invite people to understand renewable energy in a way that’s educational, accessible, and thought-provoking, and to encourage a movement away from carbon-based energy use. But they’re also designed to actually generate power via clean energy.

The official definition of a land art generator is a work of public art that captures energy from nature and cleanly converts it to electricity; pays back its environmental impact and construction cost by producing kilowatt-hours of energy; draws visitors to the site through a unique public experience; creates places for leisure and learning; does not negatively impact the environment; and increases the livability of communities.

“By building these artworks as landmarks of this time in history, this important energy transition that we’re embarking on, we can leave a mark for future generations to learn from,” Ferry says. “And contemporary generations can engage directly with the technologies and learn more about them, in a way that art is able to communicate.”

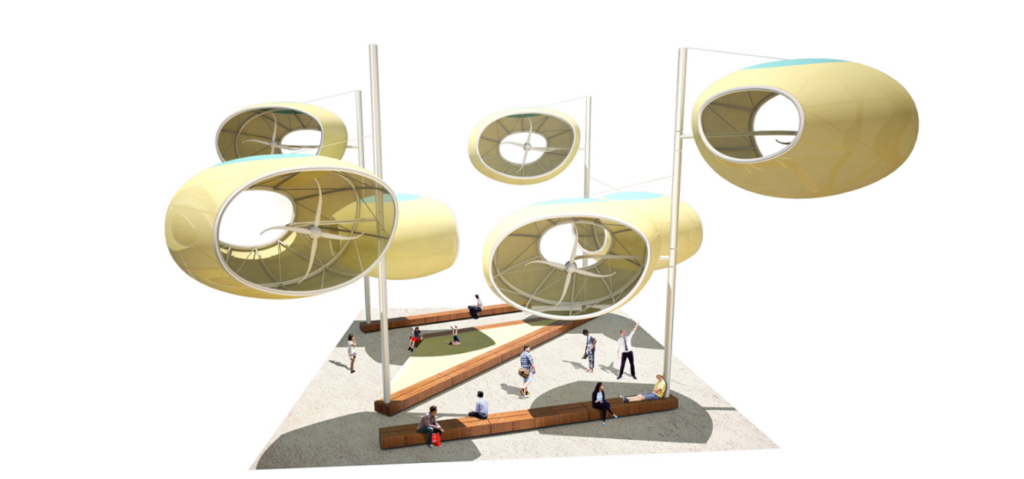

One of the first LAGI submissions now moving toward full completion is WindNest, slated to start construction in Pittsburgh next year. Led by artist and landscape architect Trevor Lee, WindNest was originally submitted for the 2010 LAGI competition, and was chosen to be built in Pittsburgh with support from the Heinz Endowments, the Henry Hillman Foundation, the Horne Family Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

WindNest will be a public installation that people can walk through and sit in, as a series of pods overhead move with the wind and generate both solar and wind energy. A display will share information on these clean energy sources, and show how much power has been generated by the installation so far. Visitors will also be able to charge their phones at the site.

The project will be a model for future land art generators, showing the potential for renewable energy sources to be integrated into urban environments and public spaces.

The shift to clean energy is especially meaningful in Pittsburgh, which sits in a region with a long history of coal production. Besides WindNest, LAGI’s work in Pittsburgh includes programs for youth and other local residents focusing on energy justice and community energy.

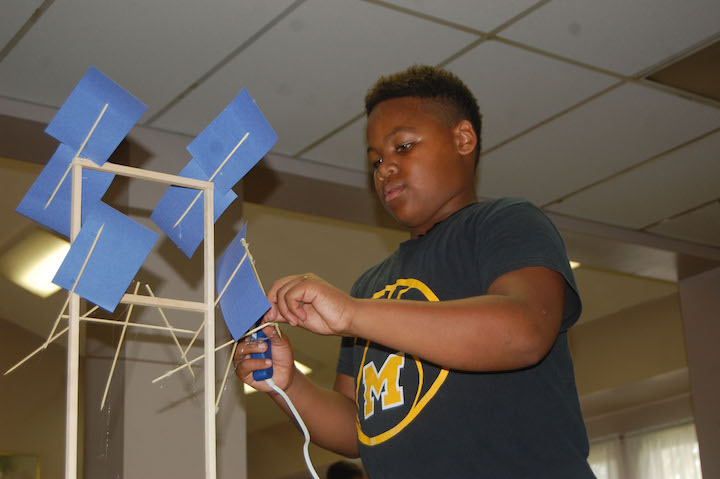

In the summer of 2015, LAGI hosted Art + Energy = Camp in Pittsburgh’s Homewood neighborhood. For six weeks, kids aged 8 to 17 learned about energy and climate science, art and design, and solar power installation. On field trips, they saw a coal mining tailings pond and the spent rod stores at a nuclear power plant.

Alternative sources of energy have a particular appeal for the people of Homewood. “There’s a really antagonistic relationship to utility companies in this neighborhood, as it’s historically redlined,” Ferry says, referring to the practice of denying or overpricing services to specific neighborhoods based on racial discrimination. “Users have their electricity turned off frequently for a number of reasons. The idea of taking control over your electricity through solar is something that resonates there.”

The campers conceptualized, designed, and built their own solar power installation, using an abandoned marquee from a dollar store-turned-community center. The piece, Renaissance Gate, is based on the structure of a torii gate, traditionally used at Shinto temples in Japan to mark the transition into a sacred space.

“Their thought was, you could pass through this gate and go away from a Homewood of fear and violence to a Homewood of hope and opportunities,” Ferry says. LAGI is now being invited to host similar camps around the country.

Individual artists, too, are using their practice to encourage discussion of climate change and to point to alternative futures. They may not be generating clean energy for wide use, but such pieces can still be large-scale, public, and strongly connected to the natural environment.

Denver-based artist Patrick Marold first developed the Windmill Project while living in Iceland, inspired by the long winter nights. The installations make wind visual by translating it into light, via a mass of light-generating windmills placed in specific outdoor locations. At night, the lights flicker like candles. Marold later brought the project to Burlington, Vermont and to Vail, Colorado, adapting the concept to different topographies and climates.

Marold doesn’t necessarily have a conservationist or educational goal in creating such installations, he says. Primarily, he wants people to engage in the physical landscape through his pieces.

Experiencing the Windmill Project, Marold says, makes visitors aware of just how often the wind blows, and what it feels like. “I want people to try to holistically consider the topic of wind power or whatever it is, rather than just forming opinions in the comfort of their home,” he says. “I would hope that the art is much more visceral and tactile, especially when you’re out there, you’re in the wind.”

Another of Marold’s projects, for the National Music Centre in Calgary, translates solar power into sound. The Solar Drones are made of soundboards salvaged from pianos that had been destroyed in a 2013 flood; they’re suspended from the ceiling. On each piece, a solar panel powers an electromagnetic system that causes a piano wire to vibrate and create a tone. The variations in power affect the sound that’s produced, including the volume and the octave that it’s in.

Marold had to make the solar panels fairly small — not much bigger than an 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper — to fit the sensitivity of the system. “I think everyone was surprised how much power we were actually collecting,” he says. “I don’t know why every rooftop in every city is not covered with solar panels.”

Another public piece using solar power was Rebecca Schwarz’s Solar Nerve, installed in 2003 in front of the municipally owned Burlington Electric Department in Vermont. In the 160-foot-long sculpture, lengths of twisted copper wire and clear acrylic rod were hung between trees, illuminated by solar-powered LED lights and connecting into a central nerve body. The wire mimicked the structure of nerves as well as of the branches of the trees. At night, the lights flashed to simulate nerve impulses flowing between each tree and the central body.

For the installation, Schwarz worked with the Burlington chapter of YouthBuild, a national organization that helps high school dropouts earn their diplomas and trade certifications while learning job skills.

“There’s a lot of grief and feeling overwhelmed about the environment. Making something that’s just going to scare people more is not how I want to approach the world,” Schwarz says. “We have some really great tools in our toolbox as artists; we can be playful and use beauty.”

For Schwarz, it’s also important to invite people into these projects. Another of her pieces, Cycle the Tower of Power, uses the concept of a carnival strength test to encourage people to produce energy via bicycle. It’s designed so that the tower of LEDs only lights up when three people are pedaling together — underscoring the point that climate and energy problems can’t be solved alone.

“The thing about cheap energy is that it enables us to really live in isolation,” Schwarz says. “We don’t really need each other; we get so much through electricity. We’re close together but farther apart.”

Patrick Marold agrees that energy sources are too removed from people’s everyday lives.

“I think there needs to be a more local connection to where your power is coming from, instead of these massive power plants or wind farms or solar fields miles and miles away,” he says. “If that source of power was right next to where you live and work, it would inform the way you use that power.”

For LAGI’s Robert Ferry, one of the exciting things about renewable energy is that it can be produced in populated urban areas. Projects like WindNest can bring solar panels and wind turbines to where people live — and that creates a huge opportunity for artists, Ferry says.

“There’s a lot of reactive pushback in communities where developers have come in and just put up three-blade, horizontal-axis wind turbines near places where people live and work,” Ferry says. “Or monotonous fields of blue solar panels — without thinking about cultural aspects, community aesthetics, and all of the things that make our cities livable and great.”

Renewable energy is changing our landscape, Ferry says, and artists should have a say in what that looks like. Ideally, he says, a “one percent for arts” rule will be established for publicly funded energy projects, so that this new infrastructure involves artists and their contributions.

Artists can also help younger generations understand and engage with climate and energy issues — as with LAGI’s camps for kids, or with Rebecca Schwarz’s latest work.

Schwarz leads workshops with kids in which they’re invited to use repurposed plastic packaging, plus solar cells and LED lights, to build their own plankton — imagined versions of tiny oceanic plants and animals.

In these workshops, Schwarz explains the plastic/plankton connection: Because plastic doesn’t biodegrade but breaks down into smaller pieces, and because it often travels downstream into the ocean, sea creatures mistake tiny bits of plastic for plankton. Then the plastic makes its way back up the food chain; when it’s ingested by humans, it disrupts the endocrine system, which can lead to cancer, birth defects, and other health problems.

Schwarz’s goal is to help the kids feel empowered, not disheartened by the magnitude of environmental issues. After teaching them about plankton and asking them to make their own creatures, she says, “I invite them to become designers and engineers and artists, to redesign the systems that we have, because clearly we need some new systems in place for how we’re living.”

Artists not only can help redesign those systems, but also can help others understand why change is necessary.

To see more examples of how public art can use and generate clean energy, visit the Land Art Generator Initiative’s blog.

This was such a cool experience. I find this to be extremely futuristic, and as such I love it. Thanks for these post.