Public Transformation celebrates & contemplates art in rural America

Artifacts line the wall of Outpost Winona: handmade art and everyday objects, each labeled with the name of a place: railroad spikes from Lake City, South Carolina; a cookbook from Alliance, Nebraska. On a table, there’s a stack of letters, each from one rural arts organization or practitioner to another, and blank cards for visitors to write further messages of encouragement. One wall displays a map of the United States, with ribbon and push pins tracing a journey across it. Here, artists and arts facilitators gathered for a weekend to discuss the role of artists in rural communities, what it even means to say “community,” and how the arts can help bridge divides and point to a shared future.

The gallery show represents artist Ashley Hanson and her collaborators’ cross-country Public Transformation tour, visiting artists and arts organizations in small towns and rural areas. The purpose of the trip: to tell stories of rural artists, to connect practitioners who often feel isolated, and to combat negative assumptions about rural places. This first Public Transformation exhibition opened October 20, and will be up through November 17.

Outpost is the headquarters for the organization Art of the Rural, which last October hosted the Next Generation Rural Creative Placemaking Summit, in partnership with the Rural Policy Research Institute and supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. That gathering’s national exchange on rural placemaking helped plant the seed for Public Transformation: Talking with people from rural areas beyond the Midwest made Hanson eager to visit and deepen the conversations — “to come to your kitchen table, and hear the sounds of your place and the smells of your place and watch you work,” she said.

After the 2016 election, Hanson decided it was urgent to launch the project right away, especially in the face of monolithic thinkpieces being written about the rural-urban divide. Art of the Rural, Springboard for the Arts and the McKnight Foundation agreed to become project partners, and with their support and recommendations, Hanson hit the road in January. Though “Gus the Bus,” her converted school bus that had become an emblem of the journey, broke down early on and “Dan the Van” had to be subbed in, the month-long tour successfully visited 127 artists in 24 towns with populations under 10,000.

“We need to be connecting with each other”

Public Transformation visited a valuable mix of organizations and artists already part of the national conversation on rural arts and culture, said Art of the Rural executive director Matthew Fluharty, alongside those who hadn’t been engaged before. Hanson filled in parts of the itinerary by Googling; some organizations were surprised she’d even heard of them.

The tour also served as a mobile artist residency; Hanson was joined by three artists for different legs of the trip, and the exhibition includes their work reflecting on the places they visited. The first artist, Randi Carlson, grew up in Minnesota and now lives in Los Angeles. After the election, she says, she felt defensive when her L.A. friends would trash people from rural areas without knowing anything about them, and she felt compelled to become more of a participant in public life instead of an observer. That idea is reflected in the interactive piece she created for Public Transformation, Storied Store. Clothing, jewelry, and other objects are displayed with price tags, but it’s only by shining a blacklight on the tags that viewers can read each item’s context. For example, one item is labeled a Zuni bracelet, but is revealed to be a mass-produced replica; such counterfeits are responsible for significant income losses and poverty for the Zuni tribe and its members.

Ellie Moore, now pursuing a master’s degree in education, has taught students in rural Idaho and in New York City. While in Idaho, she collected antlers and animal bones, always intending to use them for an art project. Her final exhibition consists of mixed-media pieces in which the bones are arranged with other found objects, displayed with the names of towns from the tour — for example, “Last Chance, Co. Pop 23.” Since she was already working with bones, it felt fated that, during the artists’ post-tour retreat to create and reflect, she read about a mythological figure called La Loba who “sings bones to life.” That legend is reflected in her exhibition’s title, Singing the Bones.

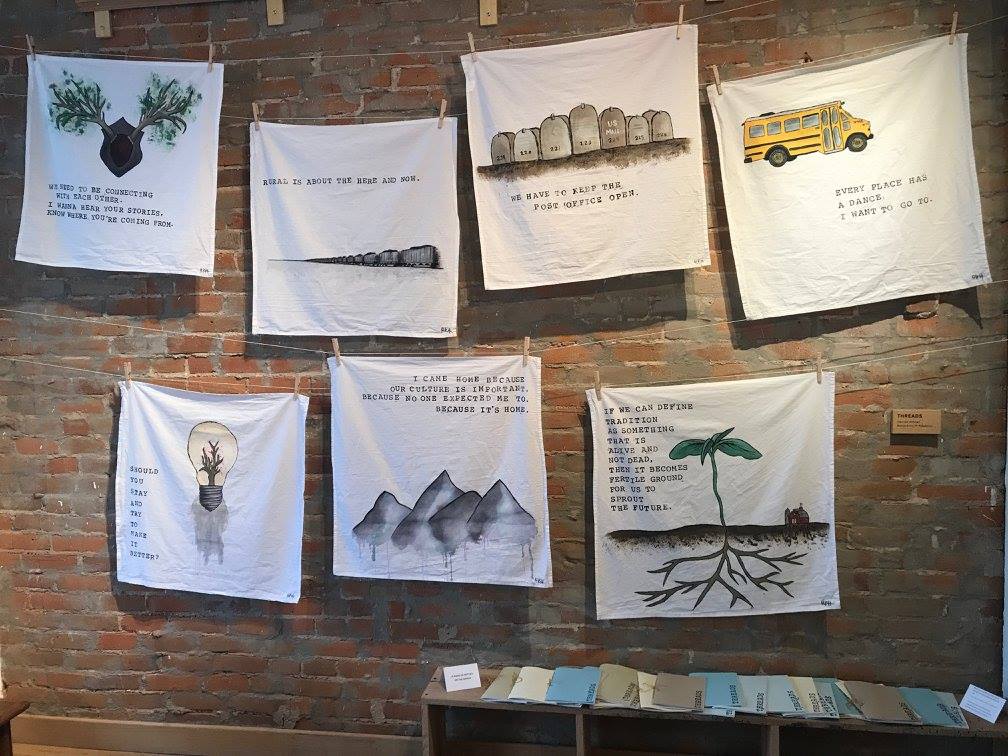

Hannah Holman is primarily a theater artist and collaborative theater maker — she’s part of a company, Savage Umbrella, that workshops shows with the public and incorporates audience feedback — so although her Public Transformation project is visual, she approached it by focusing on listening. For Threads, she found patterns among the interviews conducted with artists and practitioners on the tour, painting cloth with images and quotes. For example, one reads, “We need to be connecting with each other. I wanna know your stories, know where you’re coming from.” She also created an accompanying zine, available for sale at the gallery.

Also bringing the exhibition to life were curator Mary Rothlisberger, a rural artist herself, who goes by Mary Welcome; Outpost manager Nate Bauman, who facilitated the installation; and filmmaker Nik Nerburn, who produced short films documenting tour stops.

“We have everything a city has, but not the opportunities”

The show’s opening weekend included screenings of two short films; panels with arts practitioners; a creative workshop facilitated by the Public Transformation artists in residence; happy hour activities led by Mary Welcome, including a challenge to draw a U.S. map from memory; and Hanson’s Public Transformation presentation on Saturday night. On Sunday morning, visitors were invited to join a reflective walk by the Mississippi River, a few blocks from the gallery. Social time was built in throughout, with group meals, evening hangouts, and Polaroid photo shoots on Gus the Bus.

“So much about the whole project is about facilitating dialogue, and so it made sense to kick off the event with a lot of opportunities for deep conversations,” Hanson said. “And giving the month-long exhibition the right tone: This is meant to be interacted with, this is meant to be a conversation.”

Friday night’s film screening focused on the tour’s stop in Denmark, South Carolina. Public Transformation learned about the South Carolina Arts Commission’s The Art of Community: Rural S.C. program, which selected “Mavens” to lead community initiatives in the state’s six-county Promise Zone. Dr. Yvette McDaniel, the Maven for Bamberg County, worked with other local residents to turn a neglected lot into a “Pocket Park” and host events and creative activities there. In the film, Hanson admits that she was surprised by the humbleness of the park at first, before reminding herself that “step one” is simply creating a safe place for people to gather.

“We have everything a city has, but not the opportunities,” McDaniel says in the film, pointing to the need for funding for creative placemaking in rural areas. “If your Carnegie Hall is our Pocket Park, respect that.”

Saturday morning’s panel on “Art, Culture, and Community,” moderated by Art of the Rural’s Matthew Fluharty, dug further into small town challenges and opportunities. As participants sat in a circle of chairs, arts practitioners shared their work in Winona and southeastern Minnesota. Erin Dorbin spoke about coordinating the Crystal Creek Citizen-Artist Residency in Houston County, part of the unglaciated area known as the Driftless Region. Brian Voerding of Engage Winona outlined the organization’s mission of supporting local initiatives and involving more people in moving Winona forward.

Chong Sher Vang explained how Project FINE (which stands for Focus on Integrating Newcomers through Education) welcomes immigrants and refugees to the region and shares their culture — for example, by offering classes in traditional Hmong crafts. And journalist and poet Mai’a Williams talked about telling true stories with artistry and vulnerability. She described one of her first experiences after moving to Winona: After a group of people joyriding in a truck with a Confederate flag struck a black child in a marginalized part of town, a community meeting meant to respond to the incident ended up excluding and silencing local residents of color. “Who do we consider to be part of the community?” she asked. “Who gets automatic access, and who doesn’t?”

Questions of community and place came up again in the afternoon panel, moderated by Springboard for the Arts’ Carl Atiya Swanson, about the Hinge Arts Residency offered through Springboard’s office in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. Hinge invites artists of any discipline to live and create work on the grounds of a former state hospital, a mental health institution known as the Kirkbride building because its design followed the philosophy of physician Thomas Kirkbride.

Artists Sharon Mansur, Nik Nerburn, and Mary Welcome explained how their residencies allowed them to meaningfully interact with the town of Fergus Falls and its residents in a way that not only informed their art projects, but also built lasting relationships. The panel lineup had particular significance as Hinge was responsible for Nerburn and Welcome meeting Ashley Hanson — who had also done a Hinge residency — and eventually becoming involved in Public Transformation. Mansur lives in Winona; she debuted Dreaming Under a Cedar Tree, the piece she worked on during her residency, at Outpost this September.

During Hanson’s presentation on Public Transformation that night, she drew connections among the many towns and artists she met on the trip. Interspersing personal recollections, images, audio, and video, Hanson connected the artists and organizers she had met through a series of archetypes describing their roles – archivist, connector, translator, dreamer, mentor, rabble-rouser and others. As Hanson spoke about the different stops on the tour, she invited participants to hold and touch the artifacts from each place. For Fluharty, that was one of the most powerful moments of the weekend.

“The challenge that Art of the Rural tries to address in all of its work is this idea of distance, whether it’s geographic or cultural or structural, in terms of the immense funding gap in rural communities,” Fluharty explained. Online posts and videos are often the most accessible way to share stories, but, he said, “there is something that feels intimate and transformative and disarming when someone is talking about what it’s like in Del Rey, California, and then all of a sudden, you’re holding the tomato seeds from Nikiko [Masumoto]’s family farm, and it’s in your hand.”

That intimacy, Fluharty believes, gives Public Transformation a unique power to not only document the work of rural artists, but also stimulate further storytelling. “There’s something living here that I think will open people up,” he said.

“Who is this community for?”

Throughout the weekend — whether during the presentations and panels, or informally over homemade soup or local beer — conversations followed threads like the relationship between a place and its people, the role of artists in small towns and rural areas, and the value of connecting rural places around the U.S. despite their differing cultures and needs.

One recurring topic was the issue of political conflicts within small towns. Ellie Moore recalled attending a Sunday jam session at the Floyd Country Store in Floyd, Virginia, a weekly gathering that has been going on since the 1930s. Two of the musicians began grumbling with one another, but then were told that it was time for music, not political discussions. The tension was broken by the creative activity they shared.

Artist Mary Welcome pointed out that disagreements are often complicated by the fact that “everyone in the room is my neighbor, and when you live in a rural place, you need your neighbors. It become really complex to navigate your differences, because you still need each other every day.”

During Saturday morning’s discussion of community and who gets to be part of it, Ashley Hanson said that the question “who is this community for?” is being asked everywhere she visited on the Public Transformation tour. For many of those small towns, the answer has become “tourists” — but what about the people who live there year-round, who may have to drive to another town just to go to the grocery store? “Culture cannot be seasonal!” Hanson declared, quoting Outpost’s Nate Bauman.

Attendees talked about how the Internet has made it possible to build and choose communities across geography, and asked whether it’s even true anymore to say that a defined location equals a community. Springboard’s Carl Atiya Swanson noted that globalization and digital communication have made geography more relevant in some ways, as specific places — small towns and urban neighborhoods — try to retain their history.

Claiming a unique local or regional identity, though, shouldn’t mean using marketing to gloss over realities. That results in what Brian Voerding called “pseudo-community” — claiming that everything in a neighborhood, a town, a region, or a state is wonderful, without recognizing the people who are locked out of that vision. Agreeing that the term has become diluted through broad use, Erin Dorbin said, “I’ve kind of given up on using the word community, unless it’s for a grant application.”

Place — geography and architecture — should be a catalyst for connecting people and telling their stories, said the Hinge residency panelists. Arts and cultural activities became a way to take the history and identity tied to the Kirkbride building and help it stand on its own. The Kirkbride is the focal point, but it’s the human relationships that really have value.

That residency program is an example of the power art can have in a town, a region, or a neighborhood. If culture is more than tourism and community is more than lip service, what can the arts do in a place like Fergus Falls, Minnesota, or Denmark, South Carolina, or any of the places the Public Transformation tour visited?

For the artists and facilitators gathered at Outpost, the answer lies in what happens when a high school play or a new public art piece becomes the topic of conversation at the local gas station, instead of crime or businesses closing. Art may not solve all of a small town’s economic concerns, but it helps residents celebrate what they have and collectively look to the future.

And as those rural places seek to learn from one another, Public Transformation can be a roadmap for a new way to connect. That’s how Art of the Rural’s Fluharty sees it: “We’re on the precipice of pushing for those deeper experiences, those deeper forms of exchange,” he said, noting that Hanson’s approach offers a vital alternative to the conferences where rural practitioners usually meet. “Folks seeing one example of how this could work, I think is really going to create the space for more projects like this to flourish.”

So far, there’s just the one path traced across that U.S. map, but Fluharty imagines a future of many intersecting lines, creating new networks around the country.

That’s part of Hanson’s plan for Public Transformation 2.0: After the exhibition finishes its run at Outpost, she plans to head back out on the road to tour it, including bringing it to stops on the original trip. And she’ll continue to collect, adding to the stories and conversations from rural places across America and the artists that sustain them.