Photographer Tom Kiefer documents the things that are carried across the border

In Tim O’Brien’s short story “The Things They Carried,” the items each of the soldiers choose to carry with them through the grueling jungles of Vietnam become an allegory for the human cost of the war itself. Photographer Tom Kiefer‘s project El Sueño Americano (“The American Dream”) similarly looks at the human cost of war through the items people choose to carry with them across impossible terrain and through impossible circumstances. His war, however, is not fought in the jungles of Vietnam, but on the U.S./Mexico border.

Kiefer moved to Ajo, Arizona, just 43 miles from the Mexican border, in 2001, leaving a life, a successful antique business, and a previous career in graphic design and advertising behind in Los Angeles in order to own an affordable home and pursue a future in photography. He thought he would travel the country photographing the American landscape – mountains, cityscapes, rural scenes, cultural markers. But, he jokes, “because art rarely pays for itself,” he ended up taking a job as a janitor for the local Border Patrol station in 2003, a job he ended up keeping for over 10 years.

When he first started and for the first two years he worked there, the Border Patrol agents were collecting the food the detained migrants had carried with them as they crossed the desert and brought it to a local food bank.

“I thought that was a really great, humanizing thing instead of throwing it in a landfill,” he says. “Migrants weren’t allowed to really keep anything they traveled with, and of course they had to give up the food. So that went on for a couple of years, then there was a change of leadership at the station and that came to a halt, so all that perfectly good food was being thrown away. It was a really disgusting thing – my parents lived through the Depression and that was something you just didn’t do; you didn’t throw away food.”

Two more years passed, and finally Kiefer asked his supervisor if he could take on that role since they didn’t want agents spending company time doing it.

“His exact words were, ‘Bless you,'” Kiefer recalls.

And that was the beginning of Kiefer’s ongoing found object photography project, El Sueño Americano – when he started to see for himself the items that those caught trying to cross the border were carrying with them.

“I would see a rosary, a Bible, a bunch of toothbrushes. I didn’t know what I was going to do with these objects but they were obviously part of a bigger, much larger story,” he explains. “There were shoes, extra clothing, and blankets that I was collecting undercover because I was also allowed to recycle cardboard, plastic, and aluminum, so I just put those in the bag to donate to the local thrift shop. But other things just felt weird, like a rosary or Bible or other deeply personal items, so I just held on to them.”

“There were all these little rubber duckies,” he continues. “When I first came across them I thought, ‘Who in the hell is bringing these little rubber duckies with them across the border?’ It turns out they’re trail markers meant to guide the next group of people.”

After several years of collecting these items without any idea how he wanted to photograph and present them, in 2012 it came to him.

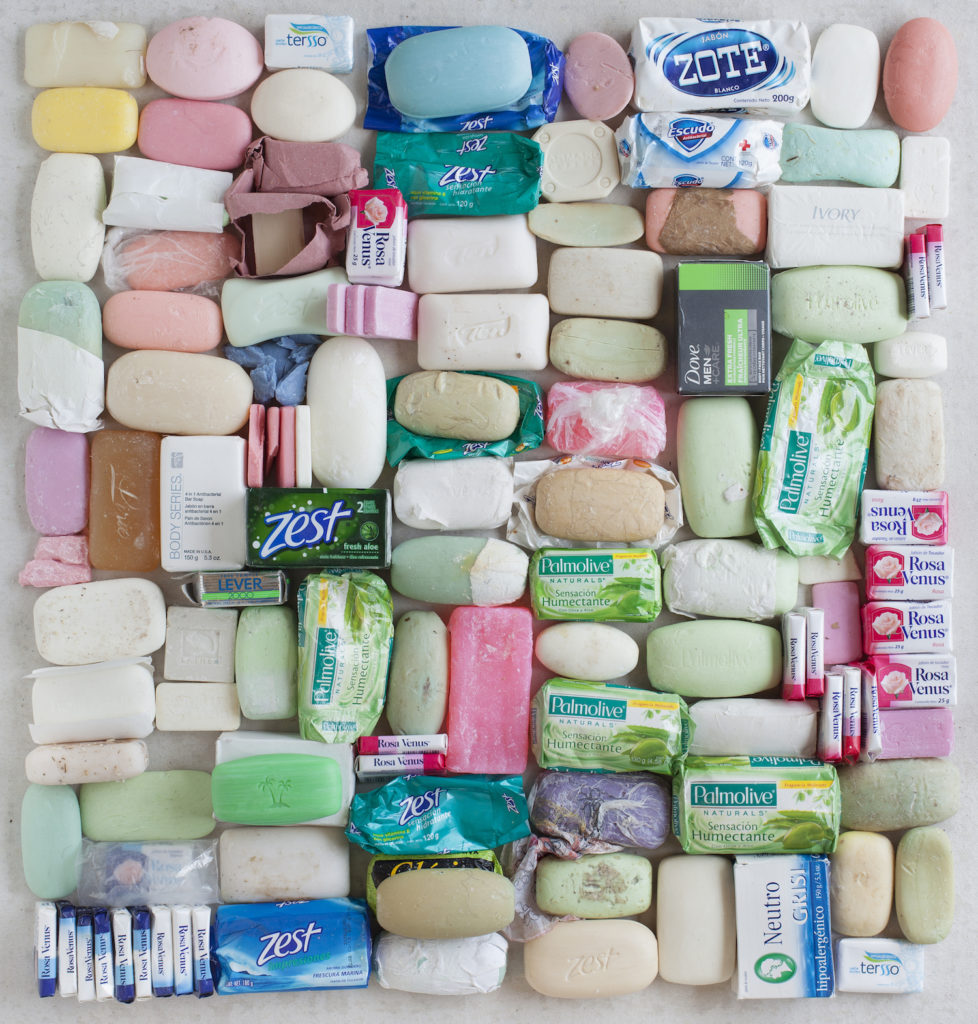

The photographs have a carefully-staged commercial-like quality to them: a stack of sunglasses could be an advertisement for Ray-Ban that you would find in Vogue. Pink-hued combs, brushes, and hair accessories symmetrically situated on a pink background mimic candy-colored cosmetics ads. Stacked cans of “Tuny” brand tuna fish are reminiscent of Warhol.

“The feedback I’ve received from people with art history backgrounds is that my work might be too artfully presented, that it doesn’t show grit and struggle, which is true,” says Kiefer. “The whole episode of risking your life to cross the desert, the unimaginable fortitude, the daring, the courage, the thing that’s propelling you, your hopes and dreams – this is my interpretation. These objects represent their hopes, their dreams, their desires. To try to create a tableau that’s dirty and grimy kind of reinforces the whole ‘dirty Mexican wetback’ stereotype. I said, ‘You know what? No.’

‘Other photographers are going out into the desert and finding these and their work is incredible. The objects I found made it to the bitter end: they weren’t discarded. That’s why I feel it’s important to present these in a beautiful, dignified way, and a way for the viewer to let them think about what this represents – the dehumanization, the struggle, the desire. Is this what we feel is important to strip from these people? These items they carried with them? I would find a bottle of cologne and think, why would they bring that with them? Because they’re thinking about their first job interview, or maybe their first date. I’m going to photograph that bottle of cologne in a way that is respectful. It’s not what you would typically think of seeing when talking about immigration and people crossing the desert. It might make people think, ‘Oh my God, that’s the cologne I use.'”

From the time he began collecting these objects in 2007 until he resigned from his job in 2014, Kiefer collected tens of thousands of objects. He would like for the collection to remain intact, and possibly display some of the objects with his photography in a few years. Ultimately he would like to see the full collection remain intact and on display at a place like the Center for Immigration Studies of Southern Arizona.

“It’s a very unique collection, a window from 2007 to 2014 of what was carried by migrants crossing into the U.S. illegally in the Tucson sector of Arizona,” says Kiefer. “There is clothing of sports teams from L.A. to New York, college and university sports teams, pens that have geographic locations on them like a tattoo parlor in Alabama, letters from loved ones in U.S. jail. It’s an absolutely one-of-a-kind collection of immigration as it was happening during those years, like Ellis Island in a sense.”

Because he was still working and collecting through most of 2014, El Sueño Americano remained an anonymous project until 2015. It has been entirely self-funded through print sales. He has begun presenting this work in exhibitions and giving talks about it, and feels an increased sense of urgency to do more in the wake of the 2016 Presidential election.

“In the back of my mind [I’m thinking], ‘This could all just end,'” he says. “This is about humanizing and educating people. They have no idea the extent to which [these people are] stripped of their belongings and how careless it all is. The wallets – no one is ever supposed to be stripped of their wallet but when they’re picked up in the desert they’re brought to the station where they’re taken in and identified, then they get on a bus to go to the next destination – if they go to Yuma, Tucson, or someplace else depending on what came up in records, in the holding cell they’re not allowed to have anything in there. The wallet gets placed in the backpack they traveled with or in a property bag, and oftentimes those bags don’t follow them onto the bus, so they’ve lost that forever. The wallet has their ID, their money, and it just disappears.”

Those caught crossing the border are also stripped of their personal family photographs, and their belts and shoelaces (for safety reasons). “So when they go through the court system and are brought, handcuffed, into courtrooms, their shoes and pants are falling off, further dehumanizing these people, many who have been here for many years doing the jobs the typical white American won’t do – cleaning hotel rooms, doing yard work, working in the service industry, in the construction industry. These are the people doing those jobs. There are 11 million people here who don’t have citizenship and for whatever reason haven’t been able to get citizenship.”

When the Trump administration began its immigration raids, Kiefer read a story in the New York Times about a man who has been a model American citizen for 20 years, married with three children, but was arrested on the charge of two DUIs he was issued in the ’90s. This man hadn’t been to Mexico in 20 years, and now might be separated from his family and shipped “back.”

“This was not the way it was supposed to turn out – the landscape of immigration and how the current administration wants to deal with it is so wrong on so many levels,” says Kiefer. “There’s this immediacy and urgency to the work and the project that I never would have imagined. We’re all reading the stories of people who have been here for years, who are hardworking contributing members of society, married with children, who are now being deported. It’s insanity. It’s crazy. People will say, “Well, they came here illegally and they have to pay the consequences.’ [And I just think], ‘Wow. You really want to go there don’t you?'”

Kiefer emphasizes that none of this was planned – he is not trained as a studio photographer. He thought he was going to go out and shoot the urban and rural landscape in traditional black and white medium format with a tripod. He says he is “just a conduit.”

“The fact that I was an artist, a photographer, coming into contact with these items and was able to discreetly save them and think of a way to present them in a way I thought was appropriate, it’s all just kind of remarkable,” he says. “It’s just like the Civil Rights Era and all the photojournalism that took place in the ’60s and how important that was. This is not photojournalism, but it is a record. My background in graphic design and advertising has been an asset in helping me present these objects in a way that I feel is respectful and that pays reverence.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

Generally, I’m not that collaborative kind of guy.

(2) How do you a start a project?

That’s a good question, I don’t really know. It seems at one point it just becomes obvious but to others it would be so obscure.

(3) How do you talk about your value (i.e., what is the “value” of what you do)?

I don’t really talk about or discuss how what I do is of value, it’s more of a place or mindset to come from, such as is this really worthwhile?

(4) How do you define/feel success?

Still trying to figure that one out.

(5) How do you fund your work?

At this point it is funded primarily by print sales, which is a very precarious and uncomfortable place to be doing the work from.

What could possibly be the reason for confiscating a bible, or a rosary? I can’t think of one, except, of course, pure meanness.