Meet Loriann Hernandez, Riverside’s “Art Hustling Roller Skating Ninja”

Loriann Hernandez – also known as “Elle Seven” – describes herself as an “Art Hustling Roller Skating Ninja.” While the overlap between street art and skating culture is nothing new, the way Hernandez’s skating converged with her art is a bit of a different “spin” on a familiar narrative.

Hernandez is based in Riverside, California, where her family has roots that stretch back over 100 years. She remembers her first forays into art were a little unusual for an 11-year-old girl.

“My uncle and cousins brought their art with them from jail and I was influenced by that first, so my first drawings were of naked women and low-riders because that’s what I saw,” she laughs. “From that point on I said, ‘I’m going to take art seriously.'”

And she did, until her style was criticized when she was in junior high and she became discouraged. It took her some time to come back around to creating art again, but once she did there was no going back.

“I had to realize one day that I was an artist and no matter what any instructors said I could still succeed in this,” she says.

She got so successful, in fact, that she saw a need that other artists had in presenting and promoting their work and saw an opportunity for her to help. She began taking classes for curating and earned a Master’s Degree in exhibition design from California State University. And while she was doing that, she was commuting on roller skates, which is how skating and art came together for her.

Hernandez taught herself to roller skate as a kid but never put much thought into it. She enjoyed doing it, but it wasn’t “cool” – at that time everyone was into rollerblading, which she hated and “sucked at.” The skates were shelved and, with the exception of a very brief flirtation with roller derby in college – “I thought it was something recreational, like dodge ball, but once I saw how seriously people took it I was like, ‘WHOA, this is NOT for me” – skating just wasn’t a part of her life until she started attending Cal Skate and opted to commute by skate because it was, quite frankly, faster than driving (this was Southern California, after all).

“I would travel between two counties every week just to get to school, and while I was doing that also I was also curating art exhibitions, teaching art in Watts and Long Beach, and also researching indigenous people’s relationship to museums and planning my thesis,” she recounts.

While she was doing this, she got pretty good at skating. Really good, actually – so good she now skates with people often less than half her age (she is 43 now, and was 35 when she started), some among the most famous skateboarders in the country.

“I got good at skating because it was survival,” she says. “Then I started skating in skate parks. I didn’t realize how good I was. I didn’t know! I just figured all skateboarders were better than me and that I just had to keep up with them so they’ll let me in the bowl. I didn’t realize I was skating with a bunch of pro skateboarders.”

While working towards her Master’s, Hernandez was already working as an art consultant, helping develop the careers of other artists. She was especially drawn to artists who might otherwise be forgotten or overlooked; artists like Douglas Miles, founder of Apache Skateboards and Apache Skate Team. The San Carlos Apache-Akimel O’odham multimedia artist and activist from Arizona incorporates Apache imagery into the hip-hop/street art aesthetic as a means of empowering Native artists and promote a sense of cultural pride and well-being among young Native people.

“I knew I had to figure out how to get him into Cal State’s Grand Central Art Center, the top art venue in all of Orange County,” Hernandez explains. “I figured out the way to get him in there was to get a Master’s Degree! And it ended up being a much bigger show than I had thought because of the communities I became involved with from my skate commuting.”

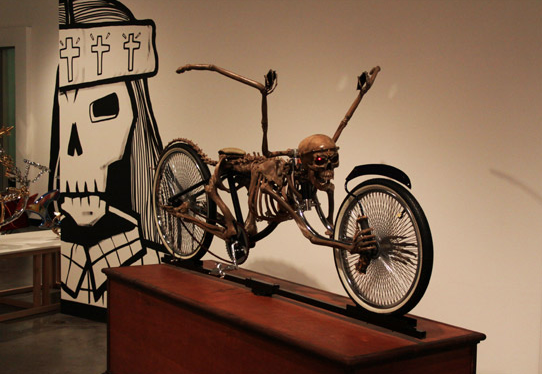

The show was called R I D E: Communities Empowering Themselves Through Mobility, and was held at the GCAC at the end of 2011. Miles was there with Apache Skateboards, as were a number of other artists from the roller derby, low-rider bike, commute biker, and transit communities, and pop artist Cory Orbendorfer also painted a mural. There was a $100,000 low-rider bike that looked like a human skeleton sitting on a coffin, and ramps were even built inside the gallery – Hernandez says she got to skate with the Apache Skateboarders, and pro roller skater Michelle Steilen, also known as Estro Jen (and one of the top skaters in America right now), did a 360-degree spin on a “tiny little ramp,” much to the surprise of everyone in the audience. The show’s opening night was a massive success, drawing in 3,000 people in four hours. Hernandez still speaks excitedly about it today.

R I D E was such a success that Hernandez took a scaled-down version of it to Senegal, West Africa. She chose Senegal because of the skate community there – thousands of people use skates (mostly rollerblades) as a primary means of transportation in Dakar because the roads are so bad and transportation is so expensive. Armed with photographs and prints from the California show and an additional $1,000 worth of supplies for the local people, Hernandez traveled to Dakar and presented the exhibition twice. While she was there she also raised money to build a few skate ramps, which became the first portable skate park in the country (and missed being the first skate park of any kind in Senegal by just three months).

Now a semi-pro skater herself, Hernandez has skated in parks all over the country, seeking out the most famous, and infamous, in the skating community, including those in the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota when she was also in the area to join in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Reservation.

“Pine Ridge was an experience in itself because there are meth heads everywhere and the skate parks are a real escape for the kids,” she recalls. “Then I went to Standing Rock for a week. I didn’t know how they would react to my skates, if they would think it’s disrespectful – like, what am I doing bringing a toy to this serious protest – but I skated alongside the protesters and just felt one-hundred percent support. I felt like I couldn’t be a better representative than just being myself there. I skated alongside Joan Baez, a bunch of awesome Native American activists, and so many filmmakers, writers, photographers, and musicians. I finally got to represent what I believe on a national level instead of just being me in my little Orange County community.”

In addition to helping to develop and promote artists and leading activist efforts – she had ran a fundraiser in order to bring supplies to Standing Rock – Hernandez now also helps people learn how to skate.

“If I can learn as a 35-year-old woman, anyone can learn,” she jokes. She runs skating classes and camps from Seattle to San Diego, and in her home of Riverside, she teaches a skating class at the Sherman Indian High School, the last remaining federally-funded Native American boarding school west of the Mississippi.

Because the kids all stay on campus and aren’t allowed to leave their dorms without supervision from a staff member, they’re stuck indoors until 2pm every Saturday and Sunday.

“I decided to bring a skating class over there to get the kids mobile and moving,” says Hernandez. “We want to make it a club for next year. They really need more than just two hours per week.”

Hernandez actually has a personal history with the school – her great-grandmother attended it in the early 1900s.

“When I went to campus when I was first fitting the kids for skates, seeing all these kids in one room I just thought, ‘Wow, they all look like me,’ which is so different from the school I went to where no one looked liked me. It’s such a contrast and this reality only exists in this little square of a campus.”

Boys and girls alike are interested in skating, and Hernandez now has a Go Fund Me page for donations so that she can get a few more pairs of skates to accommodate all the kids who are interested.

Hernandez is also about to start a teaching gig with the heavily Republican city of Riverside, which is decidedly not in favor of her preferred pastime, but she’ll still be skate commuting to work and she’ll still be holding her own at the skate parks in her off time.

“When you can get on your skates and get to work before your coworker who drove, that’s kind of empowering,” she says. “It’s also kind of empowering when I’m bombing down a hill next to a truck with a Blue Lives Matter sticker.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I like to collaborate with people who have great ideas and can contribute to a bigger vision that’s beneficial to multiple communities.

(2) How do you a start a project?

Mostly out of need.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

Mostly by sharing experiences and seeing how I can relate to others through their experiences, because you relate to a skateboarder differently than you do a museum professional!

(4) How do you define success?

When I can share the happiness with multitudes of people.

(5) How do you fund your work?

By teaching and side jobs and from the generosity of others.