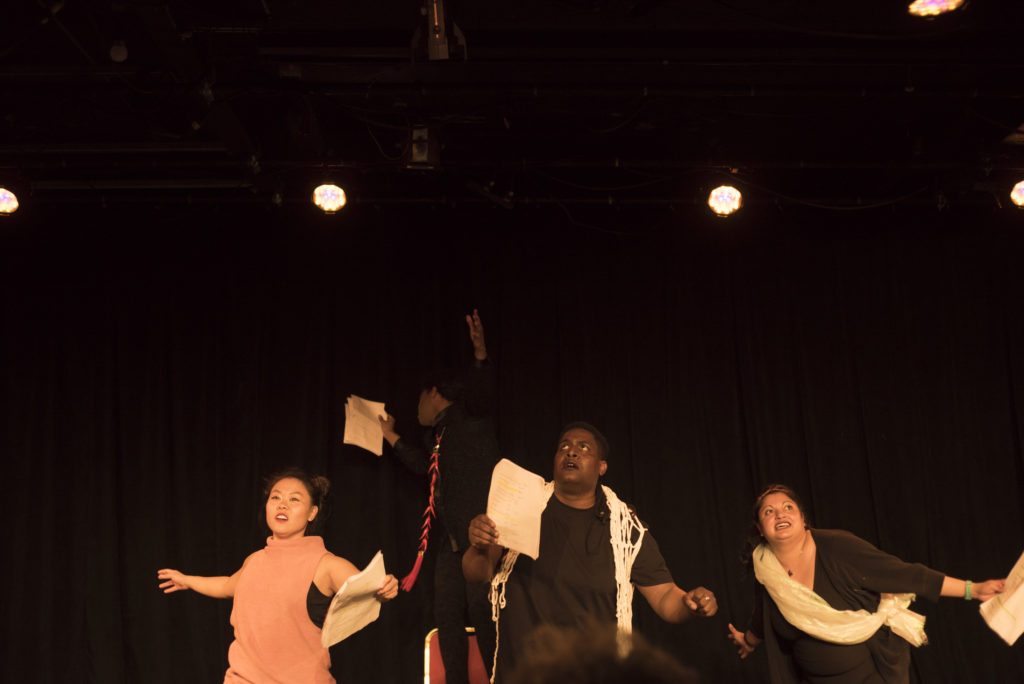

Lightning Rod is performance for the present moment

Imagine a group of artists gathering: writers, directors, and performers; many of whom have never met before; some who don’t even call themselves “artists.” They’re handed news headlines from the week, anything from the Atlantic to Cosmo, and invited to group them into constellations, synthesizing and finding connections. In the span of just a few days, their challenge is to create pieces of theater—complete with lighting, sound, costumes, and props—that interpret and respond to the stories of the moment.

The flash theater event Lightning Rod was born in 2017 as a collaboration between Minneapolis-based theater company Patrick’s Cabaret and theater artist Kat Purcell. Artist Marcela Michelle-Mobama, who participated as a director the first time around, came on as co-producer for the second installment in 2018.

Now, as part of Springboard for the Arts’ Toolkit Cohort, a Lightning Rod toolkit will be released for other artists and organizations to replicate. The format is ripe for sharing because it allows artists to respond immediately to what’s happening in the world or in their communities without extensive funding or planning.

“In theater, folks think that you need a big budget to do stuff, and/or that you need to have everything really well thought out,” says Purcell, whose pronouns are they/them. “Here, participants were able to create work in the span of four to five days that they felt really proud of, and they felt empowered by that.”

Ready to try something new

Participating artists for Lightning Rod are invited in through an open call and application. The program follows Patrick’s Cabaret’s commitment to working with “artists on the edge of culture,” including artists of color, queer and trans artists, and artists with disabilities.

That mission, combined with Lightning Rod’s collaborative nature, gives people without formal theater training the chance to share ideas and be on equal footing with more experienced artists.

“You’ll see people in roles that you don’t usually see them in,” says Michelle-Mobama, “whether that means literally the character that they’re playing on stage, or the role they’re playing in the production.”

She remembers participants’ resumes listing big professional venues in town, and others where an actor’s only theater credit might be their eighth grade play. “And those people are putting on a show together.”

A common factor, says Scott Artley, Executive Artistic Director of Patrick’s Cabaret, is that the artists are “down to experiment.” They come in with the mentality of, “I’m ready to try something. I’m ready to get uncomfortable. I’m ready to not feel totally like the ground is firm underneath me.”

The flying-by-the-seat-of-your-pants spirit became central to Lightning Rod’s ability to generate creativity. The time limitations demand resourcefulness and decisive action.

“We were completely making it up as we went along [when it started], and I think that became a big part of the organizing principle,” Artley says. “We were like, ‘We’re gonna just do it.’”

The shared challenge of Lightning Rod also rapidly cements relationships among the artists, many of whom have gone on to work together again.

“You know those escape room games where you get locked in a room with your friends and you have to find your way out? Lightning Rod is a bit like that, in building rapport and building the ability to work together,” Purcell says.

A moment during the first Lightning Rod perfectly illustrated the program’s openness to the unexpected. As a performer onstage delivered a monologue about a rainstorm, Artley recalls, the sky opened up outside and a downpour began falling on the roof. The actor mentioned thunder, and a clap of thunder sounded.

“In the context of this event about seeing what’s around us, and really noticing the beauty of the process, it’s something completely unplanned,” Artley says. “Summoning the elements in that way just feels really cool.”

Responding creatively in the moment

Despite the dark realities of many news headlines, the pieces produced at Lightning Rod have been funnier and less grim than might be expected.

“It speaks to the fact that artists on the edge of culture are constantly having to find resilience in ourselves, to carve out space, to be able to have humor, to be able to keep breathing, keep living,” Artley says. “And so seeing what these artists did with really heavy topics was one of the coolest surprises that actually ended up being not much of a surprise.”

For instance, a piece about nuclear warfare used characters to personify bombs from different countries. “That’s tragic and terrible, and also, we were laughing, and also, we knew that our laughter was undoing the power of fear that bombs can inspire,” he says.

And even a comedic take on an issue can inspire serious conversation. During the discussion after that show, Purcell remembers, audience members challenged the fact that all of the bombs were depicted as having equal power, unlike the countries they represent.

“That was a wonderful moment of this very silly, abstract play about four bombs,” Purcell says, “but it becomes a much deeper conversation about geopolitics and race in particular, in the context and in the moment, and why that racialized country would be considered to be on equal footing even though they’re totally not.”

Those talkbacks after each performance give audiences a chance to engage with and discuss current issues along with the artists.

“Someone said that they appreciated the opportunity to absorb and process the news and current events with other people, as opposed to in isolation,” Purcell recalls. “The heaviness of everything that’s going on in the world felt more manageable, and easier to process and to hold.”

The fact that headlines are synthesized to create something new also keeps it from feeling too tied to the daily news cycle churn. Ideally, the pieces can stand on their own, even be revived and expanded beyond Lightning Rod—the prerogative of the writers, as they retain ownership of their scripts.

And Lightning Rod’s focus doesn’t have to be global; the format can address specific issues within an organization or community.

“The most exciting feedback I’ve received about Lightning Rod was that people felt empowered that if they had an issue or a political or social event, and they felt like they needed to respond, that they now had the tools to do that creatively and artistically,” says Purcell.

Getting the process right

Lightning Rod may be designed to work on little or no budget, but still requires intention in recruiting participants, choosing a venue, and planning the week’s activities.

Supporting the participants is key, says Purcell. Organizations trying Lightning Rod should prepare to pay artists, offer help with childcare and transportation, and provide emotional support as well.

“Participants come to Lightning Rod with a lot of vulnerability, and a lot of passion and ideas,” they explain. “Some of those ideas aren’t going to work, and they’re going to need the space and the time and the energy and the clear head to be able to process everything that’s going on.”

The program’s mission to center artists who have traditionally been marginalized also requires producers to be aware of power dynamics, and to proactively avoid excluding people.

Michelle-Mobama recalls working with the other producers to group actors, writers, and directors for the shows—a process that’s partly random, partly based on people’s availability to rehearse.

“I was raising concerns about, oh, we have a show written by a black person with a black cast and a white director, and that will not happen,” she says. “And those things weren’t intentional things…but you have to watch out for power structures.”

Issues of power and access show up in other ways, too, as when a venue was chosen that was not accessible to people with disabilities, despite the program’s stated goal of including them.

“Accessibility means that they have access to everything that everyone else has access to, that they have access to the green room, the dressing room, not just the stage, and then you have to set up some segregated changing room or bathroom for all of the actors in chairs,” Michelle-Mobama says. “That’s not accessibility.”

The producers can share what they’ve learned from experience through the Lightning Rod toolkit, reinforcing these principles of genuine inclusion and intention.

Says Michelle-Mobama, “The limitations of randomness and expediency should never come at the expense of equity.”

Seeding a legacy

Sharing Lightning Rod as a toolkit has particular meaning because Patrick’s Cabaret is sunsetting after 32 years as a performance art incubator. After making that decision early this year, the organization’s leaders have worked to ensure that its programs and knowledge are preserved and handed off thoughtfully.

Lightning Rod will continue in Minneapolis with a planned 2019 installment to be hosted at Pillsbury House Theatre.

Patrick’s Cabaret is one of a few spaces in Minneapolis-St. Paul that have closed in recent years after featuring and/or being led by artists from marginalized communities. The chance to leave a legacy is important for these artists.

“Specifically as queer community, I’m a queer man who has been fortunate to have advisors and mentors to a certain degree, and also I’m very conscious of there being this enormous hole in my ancestry because of AIDS,” Scott Artley says. “I don’t have this community of elders to help guide me, and so it’s felt really critical, as I become an elder, to become a resource, to get things down on paper, to leave a mark in a way that my ancestors couldn’t.”

The name Lightning Rod itself pays tribute to Patrick’s Cabaret—it was chosen after a board member described the organization as being “a lightning rod for the electricity in the air.”

As other artists pick up the toolkit and try Lightning Rod for themselves, Michelle-Mobama hopes to see it used—and funded—in places like schools, after-school programs, prisons, and shelters.

Purcell hopes that it will continue to be used as a political tool alongside other tools. “It’s more like a way forward and a way of visioning than it is a direct action,” they say. “I really hope that it evolves, and I hope that it evolves differently in different places and for different people.”

Cover photo by Ari Newman.