Minnesota Through the Eyes of Joseph J. Allen

When the photographer Joseph J. Allen talks about his work, even when he’s talking about photographs of landscapes, he often talks about people. Allen describes himself as an introvert, and nothing in his quiet and measured conversational style undermines that idea. “I always envied painters who work in studios” he adds to express fondness for the more solitary opportunities in art.

“Portraiture takes a lot of you,” Allen explains further. He tells the story of an elder who wanted to be photographed in front of a sweat lodge. “I did what he wanted – he was an elder,” Allen says. To do the work well, Allen went to the elder’s house and talked to him for about an hour before taking photos. “To do really good portraits, you have to have a relationship,” then described the process of taking portraits as giving and taking, noting that “taking, exposing, and shooting represent the colonial-type language of photography.”

Philip Chaltas, color photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 1999.

Philip Chaltas, color photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 1999.

Allen offered another example to describe how he works, an example that explains a bit about his process but more about him as a person. He talks about photos he’s taken at powwows and how, for many photographers, “it’s always about the grand entry. 10 to 20 white photographers take pictures then leave.” Allen sees it as a form of imperialism “capture this and take it,” he says. It betrays a lack of interest in anything beyond the photograph, an unwillingness to engage with the people who are photographed or the culture they’re celebrating.

“I never related to those kinds of photographers.” Allen, who was born in Eagle Butte, South Dakota and is an enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, prefers to walk around powwows and not shoot until three or four hours later.

Further insights on Allen as a person and as a photographer can be seen through his journey to becoming the artist he is today. When Allen was in his mid to late 20s, he worked as an electronics technician. The company he worked for announced it was relocating to South Dakota, so Allen went back to school and studied video editing. He began working on video projects. “You need a crew for video,” Allen said, then discovered he “liked being self-contained as a photographer.”

In time, Allen started working as a documentary journalist for The Circle, a monthly newspaper devoted to Native American News and Arts. There wasn’t much income for photos, so he added graphic design to his duties, then advertising, before eventually becoming the paper’s managing editor. He worked at The Circle for about eight years.

Toward the end of his time at the paper, Allen was working very long hours and found he wasn’t suited to what he calls “journalistic fly-on-the-wall type photography. I realized this isn’t what I wanted to be when I grow up,” he says, so he left The Circle. Allen and his wife had recently had another daughter, and he wanted to spend more time at home. The time felt right for Allen to become a stay-at-home dad, and during that time he began a transition to fine-art photography.

“I was really into slide film at first,” Allen says, individual frames of developed slide film that could be projected onto a screen then he got into “black and white photos, then color. Minneapolis Technical College had a great darkroom.” Allen took at powwows using both color and black and white film, and he says he “spent days down there in the darkroom.”

Donovan and Terri’s wedding limo, black and white photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 1998. From the Minnesota 2000 project in the collections at the Minnesota Historical Society. Allen was one of 12 Minnesota photographers selected to document Minnesota at the end of the 20th century. Allen documented the urban Indian community in the Twin Cities.

Donovan and Terri’s wedding limo, black and white photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 1998. From the Minnesota 2000 project in the collections at the Minnesota Historical Society. Allen was one of 12 Minnesota photographers selected to document Minnesota at the end of the 20th century. Allen documented the urban Indian community in the Twin Cities.

Allen sold work at gatherings like the Powderhorn Art Fair and had success with galleries and shows. His wife was working in education at the time, and while thinking through how to raise two children and work as artists. (Allen’s wife is the photographer Rebecca Dallinger. Allen described her as an extrovert who likes to use a wide angle lens, and explained he was an introvert who preferred a telephoto lens.) About ten years ago, Allen and his family moved to the White Earth Ojibwe reservation where he lives now.

Before making that move, early in his transition to fine arts photography, Allen exhibited work at the All My Relations gallery in Minneapolis. Allen kind of began by considering and reexamining the iconic, and lately seen as complicated and even problematic legacy of Edward Sheriff Curtis, who photographed Native Americans in the early twentieth century.

Allen worked on a project for the Minnesota Historical Society then started to explore how different cameras would shape his art. He was given a Mamiya RB67, a medium format single-lens reflex camera favored for having a much larger frame size than standard cameras.

During this time, he worked with the Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota multimedia artist Mona Smith to photograph and document Dakota sites around the Twin Cities. In his own work, he wanted to use modern images, work with the saturated colors he admired in slide film, and was trying to get digital images to have an analog aesthetic. His time with Smith left him wanting to work on a personal project on the sites he visited. Allen contemplated panoramic photographs and cited the work of photographer Chris Faust as an inspiration.

Mni Owe Sni, (Coldwater Springs), color photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 2006.

Mni Owe Sni, (Coldwater Springs), color photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 2006.

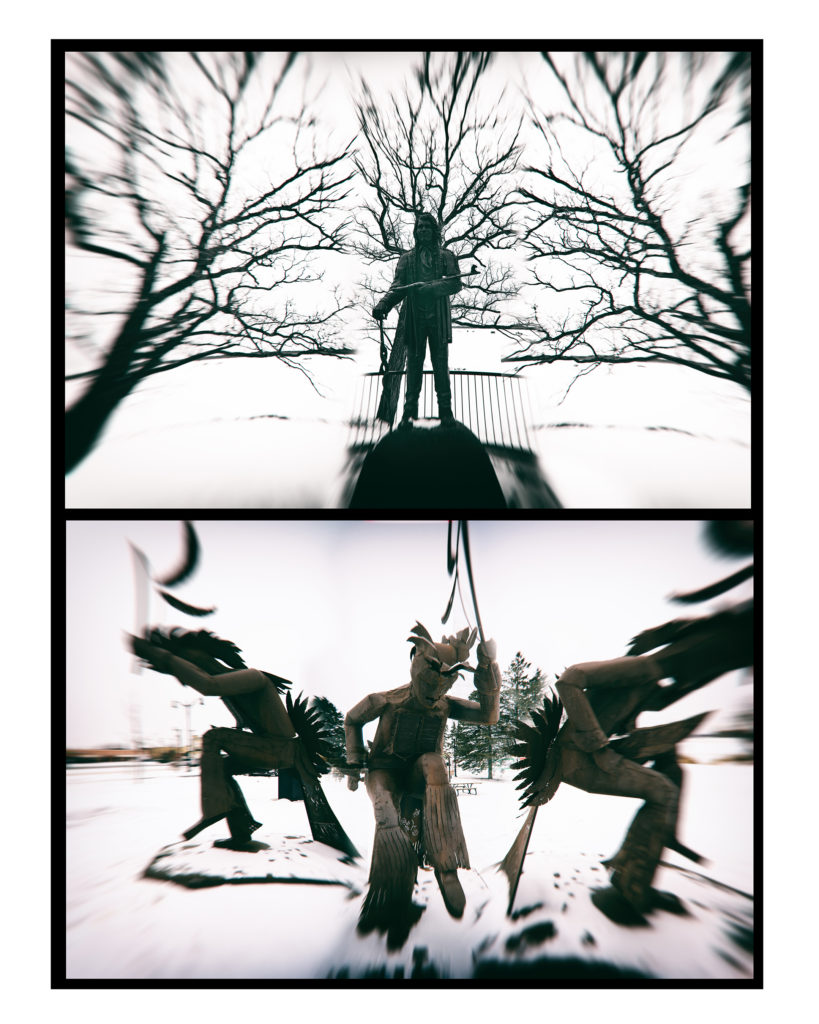

In thinking about how to take the photos he wanted, Allen confronted the financial barriers – the camera and the time in a darkroom would both cost a lot. While in college, Allen’s wife had done a project with an inexpensive Diana camera, a “toy” camera with a plastic lens that photographers sometimes use to add imprecision to the photos. This gave Allen the idea to use a Holga camera, similar to the Diana and favored for its low-fidelity charm. Allen used the Holga to create panoramics.

“I wanted the photos to be of the site but not a literal interpretation of the site. I wanted spiritual ethereal imagery that related to my life as a Dakota person, a sense of loss, not knowing things” Allen explains.

Now, Allen also works with digital cameras and has developed in it a style reminiscent of analog photography. He also works a lot with his iPhone which he describes as his “sketchbook. It’s always with me instead of carrying gear, even digital gear,” he says. “I like the instant gratification too,” he shares, talking about the photos he has posted on his popular Instagram site “I can post and hashtag and people in Japan or Russia like the photo immediately. It doesn’t matter where they are, they can see it.” He recently had an exhibit at Concordia College comprising his Instagram photos, a series of his iPhone nature photos, printed on wood using dye sublimation.

After Contact Sheet #8, digital photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 2019.

After Contact Sheet #8, digital photograph by Joseph J. Allen, 2019.

Today, Allen works as a Project Director at Gizhiigin Arts, an arts incubator in Mahnomen, Minnesota. His full-time work has left him less time for photography than he would prefer. When he applied to become a Springboard 20/20 Fellow, he says “the main draw was being able to spend time on his “main work,” meaning photography. “I wanted to be able to focus on my work and see where that would take me.” He has used the fellowship term to practice screen printing. Allen has gone through 20 years of negatives and slides learning how to make prints.

Allen is enjoying this time. His art is evolving and he’s always learning. His work at Gizhiigin allows him to help artists get their careers underway. And, when it’s the season, he collects sap in the family’s sugarbush to make maple syrup for his family. He loves life on the reservation too, shopping at the tiny local grocery store that’s been around for 100 years “you can buy just about anything, but only in one variety,” Allen says, before adding “I like to be at home.”