Caroline Woolard defines what it means to be a solidarity economy artist

The work of Springboard for the Arts is rooted in arts-based economic and community development. We believe artists are critical assets in that work, and support them by offering a variety of resources that enable them to make both a living and a life. This is why Springboard is a member of the New Economy Coalition (NEC): because we believe in the vision of a new economy, one that is just, sustainable, and democratic; one that is ethical and community-rooted; and one that does not rely on the exploitation of disenfranchised communities in order to thrive. This is the fifth in a series of stories highlighting the work of other arts-based NEC member organizations and affiliated organizations that have developed ways to sustain themselves while also sustaining artists, demonstrating that, yes, a new economy is possible. Read the rest of the series here.

In previous features examining the relationship between arts and the economy, we have focused on organizations doing work towards developing a creative economy with an emphasis on self-determining communities, financial sustainability, and economic equality. Here we are taking a different approach, profiling one single individual, Caroline Woolard, who identifies as a “solidarity economy artist.” In a written interview, we ask her what that means, how she demonstrates the intersection between art and the economy in her work, and how that work translates into real world practices. What follows is an edited transcript of that interview.

How would you describe your artistic practice? What drew you to this kind of work?

What is unusual about my approach to art-making is that I create public sculptures using both online networks and sculptural environments. For example, I build sculptures for barter only and I also co-create international barter networks. I fabricate model Shaker housing and I also co-convene investment platforms for community land trusts. I like to say that I “employ” sculpture, installation, and online platforms to study the pleasures and pains of interdependence.

I cannot make art without thinking about who has access to art because my dad was first generation to college. My parents wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer, to “get ahead,” and it took a while for them to accept that I could not live without the arts on a daily basis; to embrace nuance, build community, and communicate visually, often without words. I love working with my hands, building things, moving in space, and placing art in public spaces in relationship to specific contexts where people already are.

I think I was drawn to making public art and to making websites because I used to work the night shift a as a guard from 10pm to 6am, and I had access to the Internet at that job, so I would do a lot of reading online while I was at work at my night job. It was during that time that I learned about the solidarity economy. So I always want to make websites and physical objects, to make sure that people who might not be able to get to an event but who might be able to find someone online can do so.

I grew up in Jamestown Rhode Island, but my dad says all Woolards are from North Carolina. According to family lore, Woolard is a made-up last name. Woolard is Willard misspelled and mispronounced by settler-colonists centuries ago, hoping for a new name and a new life as tobacco farmers on stolen land. My dad, who claims to be the first Woolard ever to go to college, hid his tobacco-picking hands in books. Scholarships moved my dad off the tobacco farm.

My grandfather was a tobacco farmer who tried to rob a bank in the Great Depression to pay back debt. He failed and changed his last name; my dad was born with the fictitious surname my grandfather had made up. My dad told me this story, raising me with an acute awareness of the structural violence of poverty and also of the power of reading and imagination to motivate collective action. For this reason, I am dedicated to economic justice and I advocate for cultural equity in the arts.

How would you describe the work you are doing now?

I am finishing Ways of Being, a book about collaboration in visual arts pedagogy, with Susan Jahoda and Emilio Martinez Poppe. I am about to open an exhibition about the @ symbol at the Knockdown Center with Helen Lee and Lika Volkova, and I am making objects for facilitation for the Study Center for Group Work. Last year I started teaching art full time at the University of Hartford as an Assistant Professor of Sculpture. For the past seven years I was an adjunct faculty member at a number of schools while also working at the Laura Flanders Show and CoLab.coop.

I started making facilitation objects for gatherings because I want the physical environment of the meeting itself to be as wildly imaginative as the conversations that occur in those spaces. We often gather in self-organized groups in spaces with formica tables and fluorescent bulbs — not the most inspiring spaces. I have found that by bringing sculptural objects to community gatherings, like my Capitoline Wolf tables and my Eye Amulet timekeeping devices, I make tangible the slow temporality of community-building; people sense the care that has gone into the facilitation practices I bring to group work.

Recently, I have focused on furniture-clocks-objects for an intimate and alternative time. The timekeeping objects I have been making work like this: one large vessel is made, and filled with water. On the water’s surface, a smaller vessel is placed. The smaller vessel is made with a small hole at the bottom that allows the water to flow in. One interval has passed when the bowl sinks to the bottom of the larger bowl. In this way, the passing of time is seen. Rather than understanding time as neatly divisible, linear, and disciplinary — the project of capitalist modernization — my latest work begins with the premise that certain sculptural tools can offer an experience of an intimate time, a time which is specifically marked by our engagement with one another.

How has your work evolved from where you started?

Following the economic crisis of 2007/2008, I co-founded barter networks OurGoods and TradeSchool.coop (2008-2015). Today, I am focused on convening and contributing to the Study Center for Group Work (since 2016) for collaborative methods and BFAMFAPhD.com for cultural equity (since 2014). I also helped catalyze the NYC Real Estate Investment Cooperative to democratically finance permanently affordable space (since 2015). My life’s work is to immerse myself in the pleasures and poetics of economic justice. I create art and design for community economy projects. I aim to counter hate crimes, ignorance, and fear by inviting people to work together in immersive installations of mutual aid across differences of opinion and experience. I believe that political equality cannot be achieved without economic equality, so I work on liberatory spaces that prefigure a world that has not yet been born.

What does it mean to be a “solidarity economy artist?”

Rather than believing that the economy is a monolithic entity which cannot be altered, I aim to co-create equitable systems that privilege communal well-being over personal gain. I try to make art projects within systems that are aligned with my values. This is no easy task.

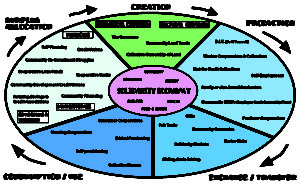

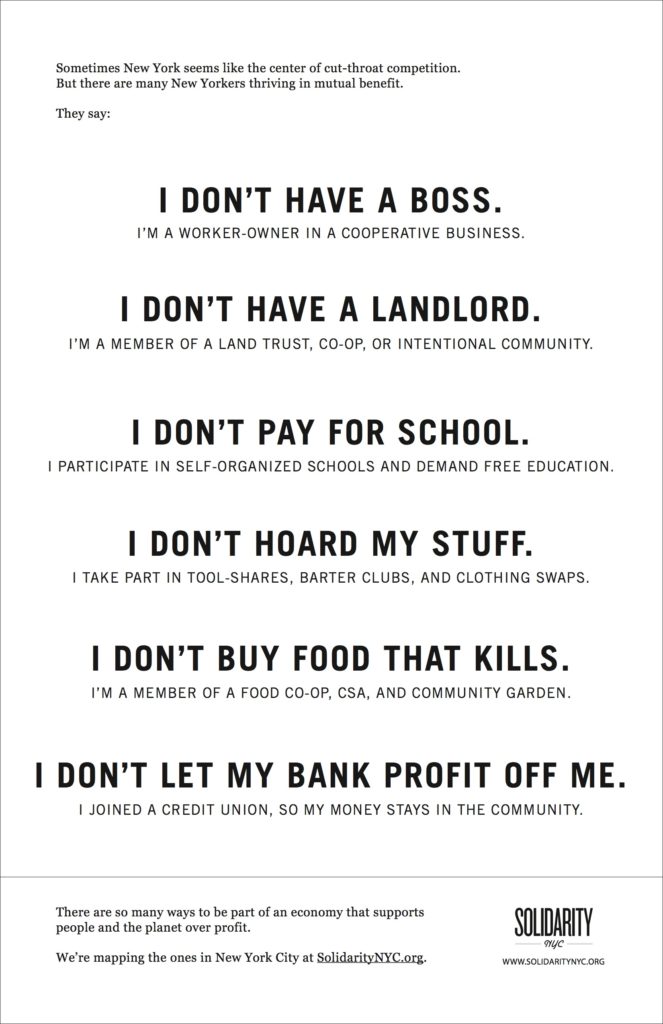

I learned about the solidarity economy when I saw the diagram above depicting the solidarity economy on someone’s wall and then found it again online in 2007. I emailed the Community Economies Collective general email address, asking for readings and connection to their work in 2008. From there, they introduced me to many people in NYC, including what would become the NYC-based collective Solidarity NYC. I started creating media, including videos, a map, a website, and this poster for Solidarity NYC from 2009-2012:

Here is how Susan Jahoda and I write about it in our forthcoming book, Ways of Being:

What might be called an “alternative” economy in the United States is known globally as the solidarity economy. This term emerged in the global South (as economia solidária) in the 1990s and is also called the community economy, the workers’ economy, the social economy, the new economy, the circular economy, the regenerative economy, the local peace economy, and the cooperative economy. It is recognized globally as a way to unite grassroots practices like lending circles, credit unions, worker cooperatives, and community land trusts to form a base of political power. The solidarity economy is a system that places people before profit, aiming to distribute power and resources equitably.

Describe an example of a project that has really underscored this connection between creative practice and economic equality. What was the significance of this project? How did it help to push forward the idea of the solidarity economy?

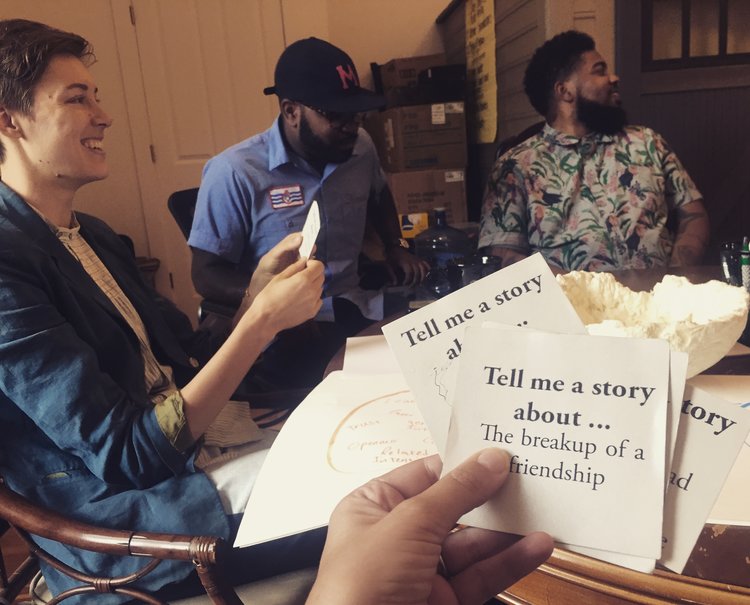

I just finished LISTEN, a year-long socially engaged art project that resulted in three listening objects made in dialog with four Cincinnati-based organizations. (Editor’s note: View Woolard’s case study on this project here.) Each object is a response to an organization’s unique way of listening: a storytelling game using small bronze objects for MORTAR and Cincy Stories, sets of ceramic cups for The Welcome Project, and a card game about cooperation for the Cincinnati Union Co-op Initiative (CUCI).

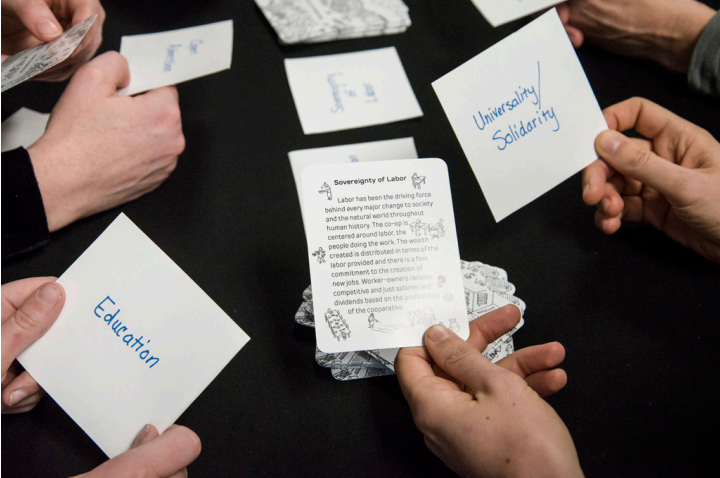

I made a more beautiful version of CUCI’s card game to teach the Principles of Cooperation with my friend Jeff Warren. The card game allows CUCI to teach the coop principles with beautiful objects that demonstrate the care that has gone into the facilitation process over the years.

Principles of Cooperation Card Game

Purpose: This teaching tool helps people learn about the ten principles of cooperation.

Timing: 30+ minutes, depending on the group

Participants: 2+

Listening tool: cards

How it works:

(1) The facilitator gathers people and places all ten cards on the table, showing the ten principles of cooperation. Each card has one principle of cooperation on the back of the card, and the definition of that principle on the other side.

(2) The facilitator asks a participant to mix up the cards and pick one.

(3) The participant will read the card they have picked aloud to the group, and talk about what that principle means to them.

(4) The group can talk about how they sense or don’t sense that principle of cooperation in their group, and how they might emphasize that principle in their group, even more.

(5) Another participant picks a card, reads it aloud, and talks about what it means to them.

(6) Repeat.

How do you perceive the relationship between arts and the economy?

There is no way to avoid make things in relationship to the economy, if we define economy as the ways in which we meet our needs. How can we go through an hour without meeting our own needs or meeting the needs of someone else?

My partner, Leigh Claire La Berge, writes about the connection between art and economy in the following way in the introduction to Ways of Being:

An artwork might have a price, but we are more concerned with its value(s). Marx says: value is a social relation. What he means by this is that “things,” whether those are ideas, property, money and so on, only have value because people have worked to make them and in that work they also produce a shared social world. Value, like meaning, is never a solitary fact; rather, it is also a relationship of interdependent wants and needs.

… Visual arts, particularly at the level of the museum or art history textbook, have tended to propagate a reified, individualized scene of production. It is no coincidence that the individual and the concept of Art-with-a-capital-A arrive on the historical scene at the same time. These are two categories of liberal, propertied selfhood; the first concretizes it, the second rejects it. Art is both the fantasy of the solitary self and, in its communicative potential, the utopian hope of transcending individual self-hood. This is the lesson that we take from the history of Marxist critical theory: that art is a deeply contradictory category of commodity being, of reified social relations, and of the opposite: of social possibility, of genuine hope, of historical newness.

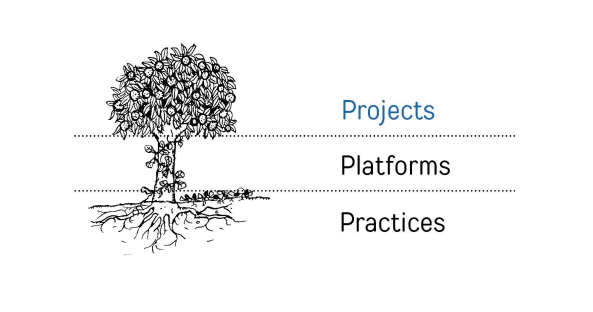

I believe that we, as artists, need to learn to think organizationally in order to imagine how our artwork and ideas might circulate in the world, and to take action. I believe that we can work together as artists to create opportunities for ourselves and for one another. I made this framework to think through the way I work, on multiple scales, using a tree as a metaphor.

Projects: The fruit and leaves; shiny and short-lived. You might also call projects artworks, objects, or events. A project is an object or experience which is produced with an imagined audience that is larger than the artist or group involved in the effort of creation.

Platforms: The tree trunk and branches; strong and enduring. You might also call platforms organizations, or initiatives, or collectives. A platform is a multi-year initiative that aims to reproduce itself in order to reliably provide support for projects.

Practices: The roots or mycelium; underground and life-giving. A practice is a way of doing things intentionally on a regular basis to develop an ability or awareness. Practices nurture platforms.

When I start a project, I ask myself: (1) Where will my artwork go, after I make it, if I am NOT intentional about it? (2) What places and people are aligned with my ideas and values, and how will I begin to find these places and people? (3) How might I join and co-create places and communities that are aligned with my work?

I made this worksheet for other people to use: http://carolinewoolard.com/static/uploads/texts/Projects_Platforms_and_Practices___Worksheet_by_Caroline_Woolard_1.pdf

There are additional worksheets on this subject available here: http://carolinewoolard.com/#finding-collaborators-and-creative-conversations-nyc and http://carolinewoolard.com/#what-successful-project

The economy art wants is one of the commons. I define the commons as shared resources that are managed by and for the people who use those resources. The commons involve shared ownership, cooperation, and solidarity: economic justice. (Editor’s note: for more on this, read Woolard’s interview in CreativeCommons.)

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I like to work with people who have shared values, but who have different personalities and skill sets that compliment one another. For example, I am like the air, zooming around, making connections between people and ideas, and thinking divergently, writing emails to meet new people, starting new projects, writing proposals, and (co-author of my upcoming book) Susan Jahoda is like a rock, checking in with people one-on-one in a deep way; editing, doing accounting, and creating folder systems. We balance each other out because I will slow down and check in more deeply with Susan, focusing our energy between big ideas and polishing each task at a high level. Susan will zoom out and dream big and meet new people with me. We also acknowledge our roles, so that we can shift them.

Editor’s note: For New York-based artists, Woolard has developed a guide to finding local collaborators which you can find here.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I ask myself: What is the thing that I cannot avoid, that I must address? And then I ask: Who is already working on this? Do they have requests out to work with artists? And then I ask: What skills, materials, resources, and gifts can I bring to this topic or context?

(3) How do you talk about your value?

My life’s work is to immerse myself in the pleasures and poetics of economic justice. I create art and design for community economy projects. I aim to counter hate crimes, ignorance, and fear by inviting people to work together in immersive installations of mutual aid across differences of opinion and experience. I believe that political equality cannot be achieved without economic equality, so I work on liberatory spaces that prefigure a world that has not yet been born.

For value as in cash, see my writing about navigating compensation here.

(4) How do you define success?

At the moment, I define personal success as deep connection with my collaborators in our daily practices of care and rigor, transforming ourselves and our craft as we work together. I’ve also written a guide to successful project reflection, which you can find here.

(5) How do you fund your work?

I fund my work with gifts, barter, and mutual aid, as well as with grants, fellowships, and teaching jobs.

[…] 25, 2018 IN ARTISTS WITH IMPACT BY NICOLE RUPERSBURG [CLICK TO READ FULL ARTICLE!] Caroline Woolard defines what it means to be a solidarity economy artist. Click To […]