Al-Bustan plants the seeds of Arab culture and community in Philadelphia

Al-Bustan Seeds of Culture started in Philadelphia in 2002 when founder and executive director Hazami Sayed wanted a place for her two young sons to go where they would learn and apply the Arabic language.

“It was certainly driven by self-interest,” she says. “My husband and I grew up in the Middle East and came to the United States for our college studies. We wanted our boys to be bilingual and be comfortable going back and forth to the Middle East each year.”

She knew that arts and culture could be a fun and engaging way to draw people in to learn the language and also learn about Arab culture and history.

Sayed came up with the idea for a summer day camp. She created a two-week program of language, arts, and cultural instruction and hosted 18 elementary school kids in a public garden owned by the University of Pennsylvania, which was how she chose the name: “Al-Bustan” means “the garden.”

The camp was a success, and by January 2003 she had incorporated Al-Bustan as a nonprofit. Since then, it has grown gradually and organically.

“Our first focus is primarily on youth and education, elementary through high school,” says Sayed. “The summer camp was the hub of our efforts for many years.”

The day camp is now offered for students in kindergarten through eighth grade. Each year the camp has a different theme, and the students produce poems, visual pieces, science projects, and more inspired by that theme. For this year’s camp, being held July 8-19, the theme is Andalusia, an autonomous community in Southern Spain that was under Moorish (Muslim) rule for centuries, a prosperous period during which this region thrived as a hub of culture, commerce, and education. Campers will learn about the history and culture of Andalusia with an overarching theme of “living together,” focusing on the coexistence of multiple cultures, faiths, and sciences across disciplines, as it was in Andalusia.

“We’re taking the inspiring aspects of Andalusian history and culture and that’s what students will be exploring,” says Sayed. “It’s a way for students to create their own creative expressions.”

The camp remains their flagship program, hosting up to 60 kids split into three age groups each year. Some students come back year after year and many come back as counselors when they’re older. Some parents make the drive in each day from New Jersey, and some families bring their children in from as far away as Texas and Florida for this unique program—truly one-of-a-kind in the U.S.

“It attracts people,” says Sayed. “Some people really believe in it. They want the arts, language, and cultural component of it.”

Sayed is diligent about offering partial and full scholarships as needed so that every child who is interested can attend.

“We have served several Syrian refugee families as full scholarships, and offered transportation as well,” she says. “We try to meet as much of the need as we can. Tuition is important because it helps pay our expenses, but we’ve never been a program that has run fully on tuition. We rely on grants for the quality and diversity of our programming.”

With only a small staff, Al-Bustan has evolved into a significant multi-disciplinary arts organization with a focus on education and community engagement. The nonprofit organizes and hosts artist residencies, annual cultural celebrations, music performances, open mic nights, community dinners, community cleanups, and so, so much more.

Each year Al-Bustan brings in internationally-renowned Arab musicians in a concert series first funded by the Knight Arts Challenge in 2011. Al-Bustan also commissions original music works, publishes recordings, and produces performance videos.

“Music is core to our programming,” says Sayed, both in terms of teaching percussion and choir to youth as well as supporting and promoting working musicians, original music, and cultural music traditions. “We’re committed to performing and presenting high-caliber Arab music and artists.”

Sayed says that in the last couple of years they have also been doing more with public art, including a commissioned mural with renowned French-Tunisian artist eL Seed—his biggest commissioned work in the United States—that was part of their 18-month-long (DIS)PLACED: Philadelphia project, documenting stories of refugees, immigrants, and those experiencing gentrification.

The mural with eL Seed was produced in partnership with Mural Arts Philadelphia. This site-specific mural, Soul of the Black Bottom, included a quote from W.E.B. DuBois written in eL Seed’s signature style of Arabic calligraphy-meets-street art, or what he calls “calligraffiti.”

Al-Bustan also now offers year-round educational programming in partnership with local public schools.

At the John Moffet School, Al-Bustan offers an after-school program three days a week that services about 50 kids each year. They teach Arab percussion, visual arts, and have a multi-lingual choir that sings in Arabic, Spanish, and French.

Another ongoing school partnership is with Northeast High School, the largest public high school in Philadelphia. The school is known for having a very international student population, with many born overseas and many who are first generation.

Al-Bustan facilitated an Intensive four-week residency by photographer/educator Wendy Ewald at Northeast High School in Spring 2017. Through this residency, they produced “An Immigrant Alphabet.”

“I’ve been following Wendy’s work for a while,” Sayed explains. “She did an installation called ‘The Arabic Alphabet’ at the Queens Museum of Art after 9/11. I went to see it and was very intrigued by her work and stayed in touch with her through the years. I’ve been trying to think of ways to bring her to Philadelphia and then the stars aligned in such a way to make it happen.”

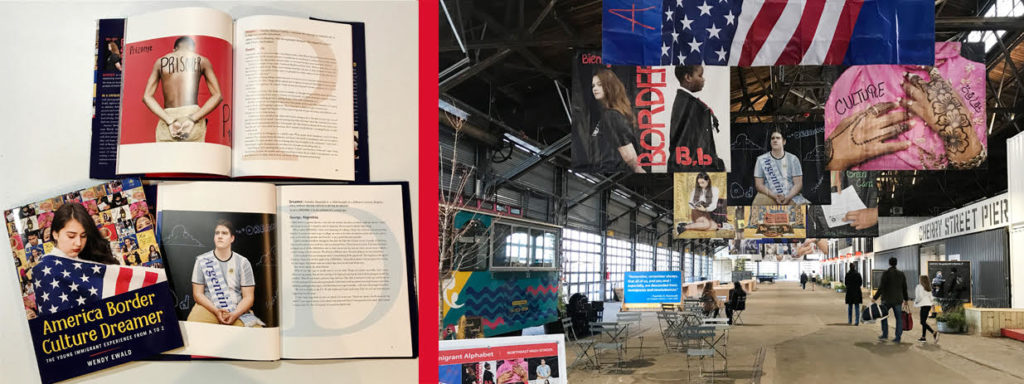

“An Immigrant Alphabet” is a series of photographs created with each of the 18 students, who together represent over 20 countries. Each chose a letter from the alphabet along with an artifact that they felt represented their stories of immigration. Ewald then produced a series of photographs featuring the students with their artifacts, and those photographs were printed out on massive 9’x11’ vinyl banners that became a public art installation. Ewald also published a book of the photos paired with the students’ stories entitled, America, Border, Culture, Dreamer: The Young Immigrant Experience from A to Z.

“We invited Wendy for a visit in 2016, but when the election happened we felt that, given that we’re at this school, we have to do something around immigration,” says Sayed. “It’s a topic that is very important to the student population and families at this school. The students never realized their faces would be bigger than life on a public building as well as in a book that gets circulated around the world. It’s very empowering for them.”

Being one of the winners of the Knight Cities Challenge in 2017 enabled Al-Bustan to make this a large public art installation with public engagement through activations at the Thomas Paine Plaza across from City Hall. The project was already unfolding as part of Ewald’s residency at the point at which they applied for the grant and then won, so they imagined what it could be as a large-scale public art installation. “The funding really allowed us to implement it in a more expansive way,” Sayed says.

The banners were initially displayed at the Municipal Services Building located in the Thomas Paine Plaza. This building is a very visible transportation and services hub for many people. The banners remained there for 11 months, and then they moved to the Cherry Street Pier after it opened in October 2018. Al-Bustan continues to engage the public with this installation through events held at the pier.

“The banners provide a great opportunity to talk to people about immigration,” says Aimée Knaus, Marketing and Events Coordinator of Al-Bustan. “Whether they’re people who are immigrants or people who know people who are immigrants, everyone has something of an immigration connection. This is a huge platform to have conversations with people throughout Philadelphia, as well as nationally and internationally. People come here to take pictures with the banners; they are known throughout the city. They’ve become this huge conversation piece.”

The “Immigrant Alphabet” banners will remain at Cherry Street Pier until mid-June 2019, at which point Sayed hopes to have the 26 banners dispersed to locations across the city. Al-Bustan is currently seeking a few sponsors to enable displaying the banners at various “host sites” —ideally outdoors, because the banners are weather-proof, so that they continue to be very visible to the public.

“The messages are very powerful,” says Sayed. “If these messages of youth voices and experiences can be seen in other venues throughout city, that would be a great continuation of the project.”

She envisions that the project could even tour to other cities throughout the country in smaller versions, with the banners reprinted on a smaller scale.

“We hope these banners can be displayed in other cities as well,” she says. “The students’ images and narratives are poignant and so relevant to the national debate going on around immigration now.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

Collaboration informs most of what we do. Our core staff collaborates on a daily basis, each bringing their strengths and insights to the work we do. We invite artists of diverse backgrounds to collaborate with other artists throughout the year. We collaborate with community partners, peer organizations, individuals, and others in whatever project or program we undertake.

“An Immigrant Alphabet” is a prime example in which the artist we commissioned, Wendy Ewald, approaches all her creative work through a collaborative process, as she did with the Northeast High School students, Al-Bustan and many other communities around the world.

(2) How do you a start a project?

Many factors lead to the conceptualization and realization of a project. From the “aha” moment in conversations with team members and partners, to our team’s interest in and pursuit of a particular artist or medium, a lot of time and thought is given to the goals of the project, the community served, and how to implement it in the most meaningful and resourceful way.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

We say this about our four core values:

Importance of Language. Full appreciation of a culture requires knowledge of its written and spoken language. Similarly, learning a language is inextricably tied to an understanding of the multiple layers of its cultural context. For those of Arab heritage living in the United States, exposure to the Arabic language can be a critical link to their cultural heritage and Arab identity.

Role of the arts. The arts are a powerfully effective medium through which youth and adults can engage in self-expression, explore cultural identity, and form critical thinking skills. The arts provide a platform to analyze assumptions through dialogue and inquiry, thereby encouraging participation in the social and civic spheres of their communities.

Artistic quality. It is important to engage the highest quality artists and teaching artists, of Arab heritage or immersed in Arab cultural traditions, to teach and present their art form to youth and adults in educational and community-based settings. This in turn provides opportunities for participants to explore new art forms, more fully develop their artistic skills, and gain enhanced understanding of and appreciation for Arab culture.

Cultural production. Culture informs arts education, which in turn shapes culture and its expression. Cultural production acknowledges that culture is dynamic, continually produced in relation to myriad influences, rather than a static set of traditions and values handed down from generation to generation. Our approach to the arts is founded on the idea that youth and adults can actively produce new cultural forms that incorporate and transform the world around them.

(4) How do you define success?

As with any mission-driven organization, success is manifested in many different ways. Success can be in the form of a young student drumming on her derbakeh even after percussion class is over because she has found a passion for this new hobby. Success can be a newly formed friendship between two attendees/participants who would have never met otherwise. Success can be when children return year after year to our summer camp and the eagerness with which some campers return as counselors and continue to engage with us in different ways through their college years and beyond. Success can be planting the seeds of curiosity and interest in the Arabic language among our students. Generally speaking, success is anything positive that comes from the efforts we put into our work, even if the outcome is different from what we had anticipated.

(5) How do you fund your work?

The majority of our funding is from grants (government agencies and private foundations), coupled with individual donations and earned income. It is important for us to remain accessible to a diversity of people, which is why we rely on grants and donations to provide high quality programming in which everyone can participate.

[…] Read the full article here! […]