A City’s Challenge: Preserving Artists’ Spaces in Denver

The story behind the Lawrence Street Artists illuminates how creatives struggled for affordable space in Denver long before the recent nationwide clampdown on converted warehouses.

It was nearly 30 years ago when Sharon Detrick and a group of artists, friends and colleagues she met while studying at Red Rocks Community College under accomplished contemporary realist Don Coen, first stepped into a drafty vacant loft on 20th and Lawrence streets in downtown Denver.

They’d spent a handful of years painting together in a “fun and funky” warehouse on Blake Street, which was razed to make way for Coors Field and Major League Baseball’s Colorado Rockies.

“I knew right away that [Lawrence Street] would be the place,” says Detrick, now 74. “Every space had a window, and you could see all the way to the mountains.”

For 27 years, the Lawrence Street Artists, a collective that ranged in size from 12 to 17 people, worked together at 2006 Lawrence St., critiquing each other’s work, co-hosting potlucks and occasionally throwing open the doors for a group show.

“Visitors who come looking for this hip hangout won’t find it unless they know where to go,” Sari Padoor wrote in The Denver Post about a show in Nov. 2010. “There’s no sign above the door. No advertising. No website. No regular hours. There is a phone, but they probably won’t answer it. They’re too busy working.”

Two years later, the collective was gone.

If these walls could talk

Detrick recalls “the ambiance” of the 6,000-square-foot space on the second floor of the brown and blond brick pre-war building. If those walls could talk, they might have told the artists that some of the creative energy resonating in the loft, despite being empty for a few years, was love left behind by Cleo Parker Robinson Dance (CPRD).

CPRD had called that space home from the mid-1970s through the late 1980s when the City of County of Denver bestowed the company with the historic Shorter Community A.M.E. Church, just off of Park Avenue West. In the years since, the converted church has arguably become the cultural heart of the Five Points community, as CPRD now includes a 300-seat theater used by many community groups, a year-round academy, a summer program and classrooms.

Denver native Cleo Parker Robinson, 68, planted the seed for what would become her world-renowned modern dance organization in the loft on 20th and Lawrence. “It was a special space, just amazing!”

Parker Robinson actually started the company in a storefront on Lincoln Street. But as a dancer and choreographer who’d studied with the likes of Martha Graham and Alvin Ailey in New York City, she yearned for an urbane dance studio.

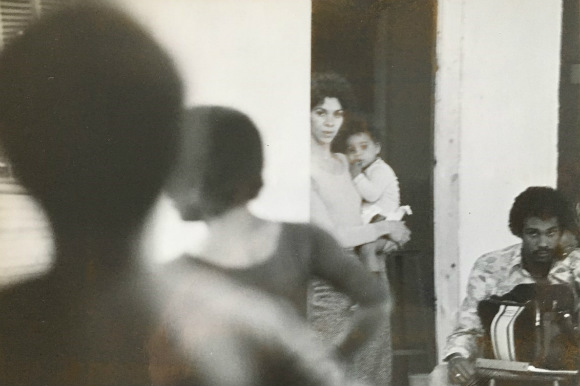

Cleo Parker Robinson holds her son, Malik, during a mid-1970s rehearsal in the space.

Cleo Parker Robinson holds her son, Malik, during a mid-1970s rehearsal in the space.

“It was just an industrial space, a big open warehouse” when she found the loft on 20th and Lawrence in the early 1970s. “We did the floors and made walls for offices. . . . It turned out to be our dream place.”

As CPRD rose, so did the profile of many of the artists and performers who passed through Denver to rehearse in the company’s downtown studio, each of them signing their name to a particular wall in the loft. Before the dance company left for Five Points in 1987, the likes of Arthur Mitchell, Eartha Kitt, Gordon Parks and The Last Poets had blessed the studio with an inked autograph. “I wanted to take that wall with me,” Parker Robinson says.

The birth of the Lawrence Street Artists

City records indicate the two-story commercial building on the southeast corner of 20th and Lawrence was built in 1930.

In 1931, it was home to the Aimel Fig Date & Nut Co. Various businesses moved into the street-level storefronts over the years including a butcher shop, a shoe repair shop, a barbershop, a tool store and the Denver Glass Co. The longest running of these is the still standing 20th Street Cafe, where a working-class crowd has been able to “get it hot, get it cheap and get it fast” since 1946.

The artists moved in upstairs after the dancers moved out. Detrick and her ilk dissected the cavernous dance studio with low walls that accommodated both privacy and socializing.

“It was everything I always wanted,” says Moe Scance, an illustrator who claimed a spot in the loft after another in the collective had departed. “The tall ceilings and big windows, and of course it was right downtown.”

In many ways, sculptor Dwight Davidson was a unicorn in the group of mostly women painters who were there for love of art rather than the need to make a living. Davidson, “an artist full-time since 1983,” was part of the core group of artists who started their downtown studio collective together.

“It hasn’t been easy,” he says of being a working artist in Denver. “There have good times and lean times.”

Dwight Davidson has been a working artist since the early 1980s.

Dwight Davidson has been a working artist since the early 1980s.

Davidson creates ceramic and bronze sculpture and tile, some classical, most whimsical, like a chubby seated hippopotamus struggling to put on roller skates, or two pigs in a loving embrace. It’s the kind of artwork that requires space, water and beefed-up electricity.

“It was nice, being around other artists,” he says of the Lawrence Street studios. “Someone might ask you to come and look at something to see what you thought. I loved that part of it, and I miss that part of it, being on my own now.”

The writing was on the wall in the months before the studios closed, Davidson says. Around the same time that the Lawrence Street Artists hosted their 2010 group show, multi-story condominium buildings went up in several of the adjacent lots, which cut off some of the natural light to the loft. Then the building changed ownership. Their new landlord worked out a month-to-month lease agreement with the artists. But he also was eager to update the space, and began renovations while the collective attempted to continue their work. Detrick and Davidson say that’s when they felt it was time to go.

The artists scattered. Some found new studio space. “Most of them went home,” says Detrick, meaning they now work out of the same place where they sleep.

The last show before the Lawrence Street Artists moved out in 2010. Photo courtesy Dwight Davidson.

The last show before the Lawrence Street Artists moved out in 2010. Photo courtesy Dwight Davidson.

Davidson makes molds and casts in a spare bedroom in his Denver apartment. He keeps his kilns in a nearby garage, and contemplates starting up another collective. But, he says, “all the places that would make good artist studios are either pot shops, grow facilities or doggy daycares.”

He considered moving to Loveland or Pueblo, both smaller Colorado cities that are experiencing a creative renaissance. But the sculptor is a regular participant in urban art shows, and teaches at the Arts Students League of Denver. “Being 90 minutes away would be too long to commute,” he says.

A new look for an old space

As it happens, in 2013, a fresh group of creatives moved into the second-story loft on 20th and Lawrence, with a contemporary, online venture that grew so fast, they are already gone, too.

DENY Designs commissions original artwork and then prints those images on housewares. Three years ago, its owners needed a contemporary place to serve as a design showroom and office. Co-founder Kim Nyhus recalls that when she first got to the downtown loft, the windows were shattered and the stairway had been removed as part of a first-floor renovation to make way for Jagged Mountain Brewery, now open at 1139 20th St.

But Nyhus and her industrial designer husband, Dustin, immediately fell in love with the building’s brick interior walls and “beautiful bones.”

“We exposed ductwork and refinished the floors,” Kim Nyhus says of the loft. The couple also installed a garage door and a vintage arcade game in their conference room, and made the entire place pop with contemporary color and pattern. “But we kept it as a very open-space environment.”

As DENY enlisted new artists and introduced new products, business boomed. “Now we work with artists all over the world,” she says. “We create anything from soft goods to furniture and all sorts of wood wall art.”

DENY Designs occupied the space after Lawrence Street Artists, but also recently vacated it.

DENY Designs occupied the space after Lawrence Street Artists, but also recently vacated it.

And so they needed a larger space where DENY could consolidate sales and production with manufacturing and shipping. Even with capital, the Nyhuses bumped up against the same real estate challenges as independent artists. When they went looking for a fresh space last year, Kim says, “It was our intent to stay in Denver, but the availability of commercial real estate was at an all-time low,” between the size and specifications that they needed, “and all the marijuana businesses that come in just before you and pay cash.”

According to the Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation, the city closed 2016 with an office vacancy rate of about 10 percent and an industrial space vacancy rate of just under 4 percent.

DENY Designs is now located just south of Denver in a 27,000-square-foot Englewood warehouse.

Denver artists dig in

Artist have always used warehouses for their work, and yes, sometimes they sleep there. Such was the scenario in Oakland, California’s Fruitvale neighborhood last month when three dozen people ages 17 to 39 died in the Ghost Ship warehouse fire during a house music party. As part of an arrangement mirrored in high-rent cities everywhere, artists and musicians reportedly worked and lived together in the 10,000-square-foot Ghost Ship space, some of them with children.

As we now know, the warehouse was not zoned for residential nor entertainment purposes, and did not meet city code requirements for the event that unfolded there on that fateful night in December. Speaking days after the tragedy, Julian Castro, outgoing head of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development said, the “incident, in a very intense way, has highlighted the need to create more housing opportunities” across the country.

Nonetheless, with public safety in mind, officials in cities nationwide began evicting artists from shared warehouse spaces, which resulted in the closure of Rhinoceropolis and Glob in Denver. Among the issues: The city prohibits more than four unrelated people from sharing a single domicile.

Pale Dian performs at Rhinoceropolis. Photo by Tom Murphy.

Pale Dian performs at Rhinoceropolis. Photo by Tom Murphy.

Denver artist, educator and arts columnist Lauri Lynnxe Murphy is part of a grassroots group catalyzed by the recent warehouse clampdown. The artists came together in outrage over what happened at Rhinoceropolis but are now mobilizing to address the big-picture problem: That real estate prices in Denver are squeezing out the same people who helped make the city’s urban neighborhoods desirable in the first place.

“There are studio buildings that open up and provide a sense of camaraderie. Those are becoming more and more expensive,” Murphy says. “The real problem is living space. People can’t afford to have both” a studio and a living space in the city.

According to Zillow, metro Denver’s average rent was $2,006 in Nov. 2016, the highest of any major city not located on a coast, a 39 percent jump in five years. Compare that to Chicago at $1,637, Dallas at $1,556 and Phoenix at $1,301 a month. Zillow is also calling for Denver’s already elevated rents to rise another 2.5 percent in 2017.

So how do artists in Denver make it work? “They’re either working in their homes or they’re not working at all,” Murphy says. “I know artists who are just giving up.”

What about the argument that struggle breeds great art? “I hate it when people say that!” she adds. “I don’t think struggle makes great art. I think money and time make great art. If you’re busy thinking about how to keep a roof over your head and food in your belly, you are not making your best art.”

The Sekhunts perform at Glob during Titwrench. Photo by Tom Murphy.

The Sekhunts perform at Glob during Titwrench. Photo by Tom Murphy.

Photos by Kara Pearson Gwinn, and courtesy Tom Murphy, Cleo Parker Robinson Dance, Dwight Davidson and DENY Designs.

Launched during the 10th annual Denver Arts Week, this story is the second in a four-part series funded by the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and produced by Confluence Denver and Creative Exchange examining he impact of art and artists on Colorado’s evolving capital city.

Elana Ashanti Jefferson is a Denver native and longtime cultural affairs journalist. Her work has appeared in House Beautiful, Lucky, Popular Mechanics, The Denver Post and the Denver Business Journal.

[…] Civic Center Building. Read stories as part of this series on graffiti and development in Denver, artist spaces and displacement, and percent for art […]