Microloans help artists build sustainable careers

Blayze Buseth was ready to launch his career as an artist. As a ceramicist, he had received several requests for commissions, particularly for his “Legacy Vessels,” or customized cremation urns. He also hoped to open a studio space and showroom in his hometown of Fergus Falls, Minnesota. Blayze saw the potential to turn his art into a successful business, but he needed some money to take the next step.

Artists like Buseth can try to cover materials, studio space, travel, and other costs simply by selling their work — but it may take some time to attract customers and build up positive cash flow. Artists can apply for grants from nonprofits, foundations, or state and federal arts funds — but such grants are awarded only to a fraction of those who apply, and they’re typically meant for specific projects. Artists can launch an online crowdfunding campaign — but those require a significant investment of time and effort, plus an existing network of friends and fans who can help reach the goal.

Partnering with established platforms to support artists

For Buseth, the best solution was one that’s emerging as an option for artists: a microloan.

Microloans can help artists bridge the gaps between other sources of funding. An artist might be able to cover the materials needed to fill their first big commission, a down payment on their own studio, fees for conferences and fairs where they can show their work and reach new people, or any of a number of jumping-off points for their career.

“I’ve been thinking about all these different aspects of how to move forward [as an artist] for a while, and this is really what I needed to be able to pursue all of those options,” says Buseth.

Springboard for the Arts, parent organization to Creative Exchange, is among those currently testing a microloan model. In August of this year, Springboard announced a new partnership with Kiva, a microlending platform that funds small businesses around the world.

Kiva applies the concept of crowdfunding to a system of lending, allowing members to support small businesses and entrepreneurs with loans instead of donations. Through the new partnership, Springboard is a Kiva trustee that can invite artists to apply for loans and endorse those artists on the Kiva site. The partnership also includes Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), which works with Springboard as a community development intermediary in other programs as well. LISC’s small business lending program matches dollars loaned through Kiva to help artists reach their goals.

“Grants are great, but when you apply for a grant or fellowship, you’re putting that timeline and power and agency in someone else’s hands, to decide if you get that money,” says Laura Zabel, Springboard’s executive director. “At Springboard, we like platforms or mechanisms that put the power back in the hands of the artist. It’s a much more active way that you can pursue building your business.”

Kiva loans are offered for up to $10,000, at zero interest. When a borrower applies for a loan through Kiva, they must go through an underwriting and approval process. Then, the borrower raises money toward their loan in a fundraising period, similar to a crowdfunding site such as Kickstarter. Individual investors who sign up on the Kiva platform can contribute $25 or more to the loan. After the fundraising goal is met, the borrower receives the loan. As the borrower pays back the loan, those who contributed are individually repaid.

Though Kiva resembles crowdfunding platforms, it has a few important advantages that made it appealing. For one, Kiva has a community of users who regularly invest in small businesses through the site. In fact, most loans are funded by 20 percent friends and family and 80 percent the Kiva community. That puts less of a burden on the borrower to rally support in their personal circles, making it more viable for artists who may not have a wide network of supporters who can give.

Kiva also encourages ongoing investing, because loans are repaid back into a user’s Kiva account. Once someone has contributed to a single loan through Kiva, it’s easy for them to simply continue investing that money into small business after small business: They can choose a new project to support each time a loan is repaid.

Buseth was a good candidate for a Kiva loan because he had attended Work of Art business skills workshops (also available as a toolkit!) at Springboard’s office in his hometown of Fergus Falls. Naomi RaMona Schliesman, a Springboard artist development coordinator, knew Buseth through those programs and as an artist in the community, and she recommended him for a Kiva loan. His Work of Art Experience, as well as support from Schliesman and Kiva staff helped with business and repayment plan development, as well as marketing and promoting the Kiva campaign. Buseth’s Kiva loan was successfully funded in August 2016.

As a result of the loan, Buseth can now move forward with his studio/showroom space, which is currently under construction, and attend the National Funeral Directors’ Association conference to learn more about the field and see how other sellers market their work. He’s also been able to experiment with 3D printing of his pieces.

Besides putting down local roots with his new space in Fergus Falls, Buseth has been able to grow his audience nationally and internationally through Kiva. He’s connected with supporters who not only offered major support by lending through Kiva, but also have stayed in touch with him since his loan was funded and have purchased artwork from him.

The arts are a relatively small piece of Kiva’s work for now, but the company is expanding its work in the U.S. and with artists. Springboard and LISC’s partnership with the platform may pave the way for more arts organizations to try it.

For Springboard, their work with Kiva will be part of a broader effort to educate artists about loans and make them aware of opportunities to borrow capital.

“I think that lending is something that historically artists haven’t really thought about as being for them, or haven’t been invited to consider,” says Laura Zabel. Kiva, she says, is one of a larger set of loan-based options that artists can explore.

Alternative capital for community artists

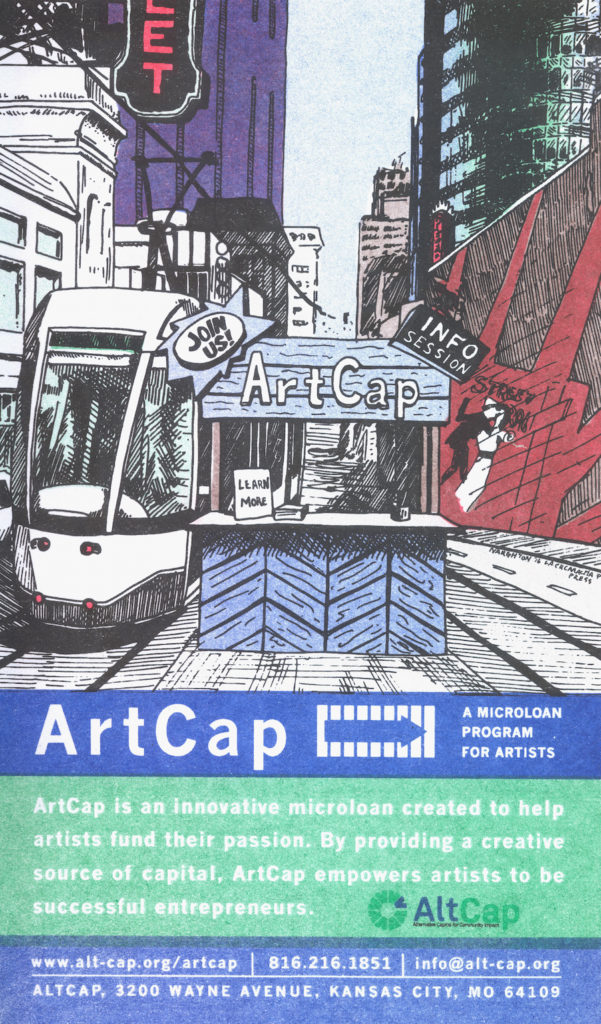

Kiva isn’t the only way microloans are reaching artists. Kansas City’s Office of Culture and Creative Services, created just last year, is leading a microloan initiative as part of their mission of supporting artists’ contributions to the local economy and retaining talent in the region. The office’s partnership with AltCap, a community development financial institution, allows them to work with an organization already investing in the community. AltCap looks for ways to provide alternative sources of capital to those not adequately served by traditional financial institutions. The organization also offers business and entrepreneurship training to local residents. The artist microloan program, “ArtCap,” was announced in February of this year.

ArtCap has funded two artists so far, including Nick Naughton, owner of the print shop La Cucaracha Press. Naughton, in turn, has supported ArtCap by designing an informational poster for the program.

Like Springboard for the Arts, AltCap sees microloans as an option for artists to fill in gaps between other sources of funding and to take the next career step. They’re also a way for artists to build credit and work toward bigger loans in the future, says Megan Crook, who joined AltCap this year to lead the new program.

Like Springboard for the Arts, AltCap sees microloans as an option for artists to fill in gaps between other sources of funding and to take the next career step. They’re also a way for artists to build credit and work toward bigger loans in the future, says Megan Crook, who joined AltCap this year to lead the new program.

Because credit-building is a benefit of the loans, the organization does their best to help artists become able to take out a loan in the first place. If an artist can’t take on any more debt, Crook says, the ArtCap program will refer them to other financial literacy and support resources within AltCap or elsewhere in Kansas City.

ArtCap emphasizes that it’s important for each artist to put together a business plan, much like Buseth did with his Kiva loan. A clear vision for how they will use the loan, Crook says, is more important than a specific credit score or other requirements. ArtCap currently consults borrowers one-on-one, but plans to build a full training program that can help artists prepare for and make the most of a loan.

Microloans for musicians

In the music industry, microloans could become a widespread alternative to traditional artist-label relationships, allowing artists to receive financial support while staying independent.

The Rootfire Cooperative is providing zero-interest loans to musicians, primarily reggae artists. Rootfire began as an artist management company, but shifted to a cooperative that supports performers and hosts events in the reggae scene.

Rootfire owner Seth Herman had noticed a trend of artists being reluctant to sign with labels because they didn’t want to turn over a portion of their album sales or partial rights to their music. At the same time, artists who wanted to self-release albums would often ask their managers to help them run Kickstarters or other crowdfunding campaigns — requiring the managers to put in significant time and effort just to raise the money to make a record.

The idea to use microloans to fund album releases came about when some longtime friends of Rootfire asked if they could put their next album out on the Rootfire “label.” Though Rootfire isn’t a record label, they’ve achieved a brand recognition that this band wanted to be associated with. Rather than setting up a traditional label model to release the album, Herman proposed a system in which Rootfire would simply be invoiced for the costs associated with the album release. The band could then repay the loan with money from their album sales, at zero interest. Rootfire could also offer professional support for the album release, providing some of the label-style structure that a fully self-released album would lack.

Rootfire released three albums this year using this new microloan model — by artists The Movement, HIRIE, and Giant Panda Guerrilla Dub Squad — and all three debuted at number one on the Billboard reggae chart.

The system works, Herman explains, because Rootfire’s business model is not built around album sales. Their income from events, as well as their investment partnership with Ineffable Music Group, allow them to fund the album release loans without feeling that the money is coming out of their expected profits.

So far, these loans depend on personal relationships and trust between the artists and Rootfire in what is a small and loyal scene. It’s also important, Herman says, for bands pursuing these loans to have a certain level of professionalism and experience. That said, he does see the potential for this model to grow and become a third option for artists alongside major and independent labels.

Like ArtCap’s microloans and Springboard for the Arts-endorsed Kiva loans, Rootfire’s subsidized album releases allow artists to take the next career step more quickly and confidently than they could otherwise.

As with ArtCap and Springboard’s partnership with Kiva, too, the Rootfire Cooperative is still new. All three initiatives are in an experimental phase and will continue to evolve, and for now, all three are operating on a small scale that involves direct interpersonal support. But all three have leaders who see microloans as a model full of potential: to empower entrepreneurial artists, to allow individuals to invest meaningfully in their communities, and to support sustainable careers in the arts for a growing number of people.

[…] need to make a living and a life.” Springboard has recently announced a new partnership with microlending site Kiva to help artists access resources to create sustainable businesses and […]

I’m from Johannesburg, south Africa… I would like to have a loan to start my career artist career