How place and cultural assets can come to define a community’s long-term goals for revitalization

These stories are brought to you by a partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts and the NEA’s Our Town program.

Most Angelenos perceive Willowbrook and the adjacent communities of Watts and Compton as ground zero for poverty, gang violence and low educational attainment; but like many communities, Willowbrook is comprised of complex identities.

Just south of downtown, it is adjacent to both the Watts and Compton neighborhood areas of Los Angeles. With over 35,000 residents, Willowbrook is a significant population center. A Los Angeles County Metro Rail station—Rosa Parks Station—at the intersection of Imperial Highway and Wilmington Avenue is a major transfer point for regional commuters. Poised to reopen in 2014, the Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Hospital will again become a flagship of the community.

The unincorporated area of Willowbrook is a blend of urban, suburban and even rural qualities (evidenced by long narrow lots, horse trails, vast backyard crops). The area has long been predominantly African American, but in recent years, the Latino population has surged. The 2010 census reported a 23% African American population and 63% Latino, up from 54% in the 2005 census.

Willowbrook is also a transportation and health hub. With the MLK Medical Campus reopening in 2014 after its controversial shutdown in 2007, the area is now seeing significant investment by the county. These capital and infrastructure improvements are restoring medical care and hospital-related jobs, helping to address the high unemployment in the area that followed the Great Recession.

Willowbrook had a number of projects on the table related to infrastructure improvements, improving health services and community development, but even though the county was making investments, it was not clear how Willowbrook’s distinct identity would be reflected in the capital and infrastructural improvements work it was doing.

Ways to Listen

1) salons/technical assistance workshops for local artists,

2) community JAM sessions and public engagement led by local artists,

3) pedestrian scale billboard to help collect voicemail and text messages,

4) door-to-door resident outreach,

5) community showcase and home and garden tour.

LACAC tapped two key partners to implement the project: LA Commons and artist Rosten Woo. LA Commons, a nonprofit organization that works with local communities throughout the Los Angeles area to facilitate and help materialize local art practices, provided preliminary research, conducted community member interviews, and mapped the area’s cultural assets.

Los Angeles-based artist, writer and educator Rosten Woo was experienced with this type of work, having co-founded the Center for Urban Pedagogy, a New York-based nonprofit organization that uses art to encourage civic participation. Woo contributed artistic vision and expertise in public engagement and urban planning.

Numerous local organizations served as on-the-ground community organizers, conducting outreach, hosting focus groups, connecting the Project Willowbrook team with additional stakeholders, and giving team leaders feedback on the project. Their intensive engagement gave the project validity in the eyes of residents, which ultimately strengthened the project’s content, audience and relevance.

This project was not the first time groups had developed visions for Willowbrook. If anything, in fact, the community had developed planning fatigue, and felt tired of contributing to visions, over the course of decades, that went unrealized. So for LACAC, the challenge was not only to make a visioning tool, but also to develop real relationships of trust with residents in order to overcome disillusionment with the planning process.

The team split the project into two phases. In the first phase, LA Commons and LACAC did extensive interviews with community members and mapped the area’s existing cultural sites and activities. This process allowed the team to understand its site and to develop relationships with key community stakeholders and residents. “To really embed an artist in a community for cultural observation and relationship development,” said LACC Assistant Director of Civic Art Letitia Ivins, “we realized partway through that we needed at least a year or more.”

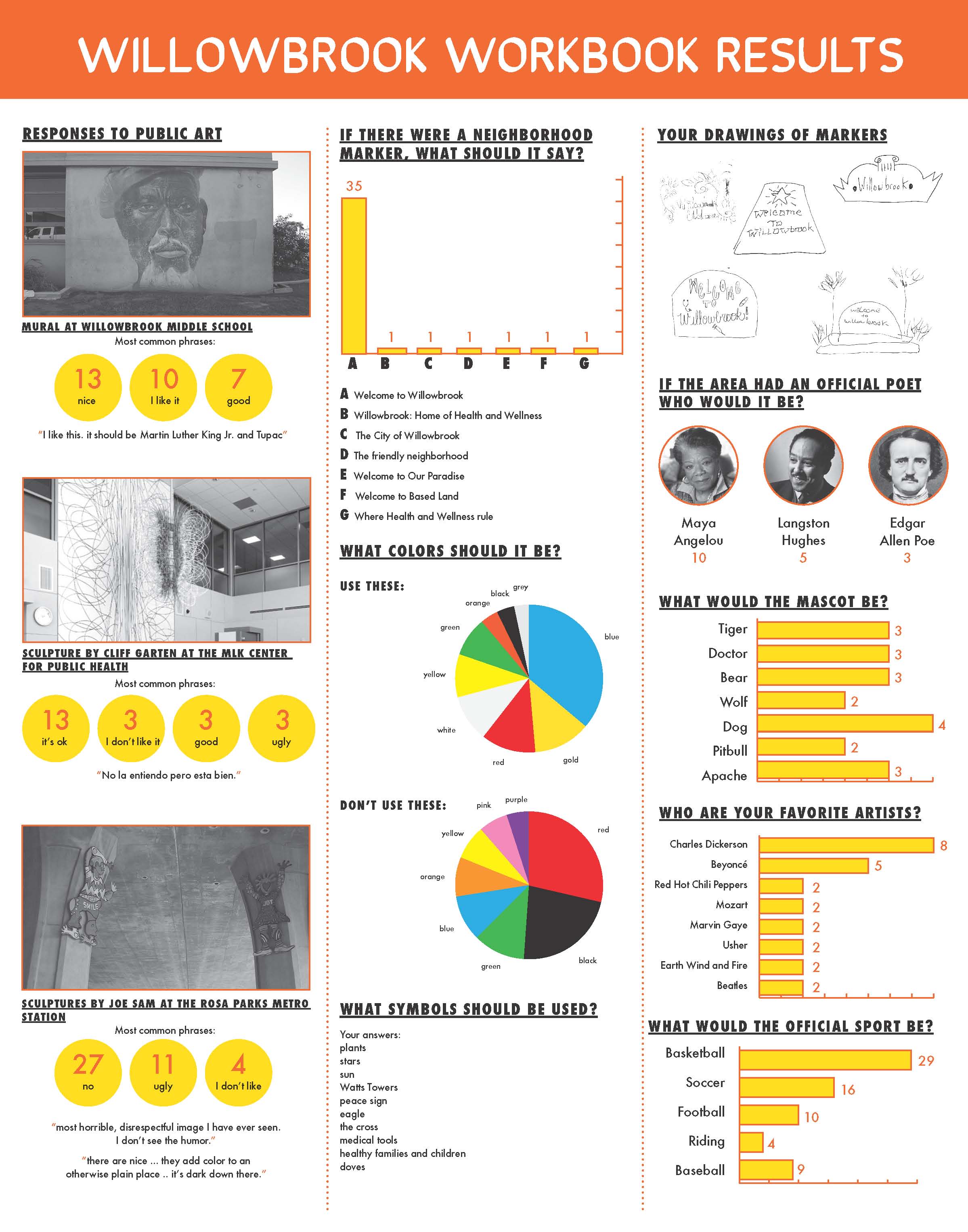

Then, in Phase II, led by Woo, the team developed novel approaches to involving the community in communicating and developing the visioning document, culminating with a magazine-like survey and visualization of results, a community showcase, a home and garden tour and book, and the visioning document, “Willowbrook is../es…”s all of which included the many contributions of community members themselves.

The cultural asset mapping yielded a community-driven document meant to serve as a way to coalesce different ideas outlined by residents and as a framework for the future of Willowbrook. A cultural asset mapping report also proposed four options for future cultural programming, including a “Community as Classroom” plan that would pair teens with artists in site-specific projects, formation of a public space for community gatherings, exhibitions and workshops, a dance education program, and an initiative that would position local artists in a broader Los Angeles focus on healthy communities.

The project gave different county departments a vision around which they could develop their own strategies in a coordinated way. As project consultant Ed Stevens said, “The project strengthened the County’s approach to community development by ensuring that the place-defining cultural characteristics and opportunities of Willowbrook were acknowledged, supported and written in the blueprints of its long term future.”

The project gave different county departments a vision around which they could develop their own strategies in a coordinated way. As project consultant Ed Stevens said, “The project strengthened the County’s approach to community development by ensuring that the place-defining cultural characteristics and opportunities of Willowbrook were acknowledged, supported and written in the blueprints of its long term future.”

Considered a significant outcome by LACAC, the County departments of Parks and Recreation, Public Works, Public Health, and Regional Planning now look to the LACAC plan as the basis of community and public engagement. In addition, a representative of LACAC was appointed to serve on the interdepartmental Health Design Workgroup, reinforcing LACAC as a critical resource in developing new policies and practices around health.

The project captured the community’s imagination in ways that were far more enthusiastic than previous attempts at planning Willowbrook had. This positive reception is evidenced by the community holding book launch parties for Woo to celebrate the community-sourced visioning document.

Parts of the process were very experimental. A “Home, Garden, and Vehicle Tour,” for example, was a novel program developed by Woo that became an important mechanism for allowing residents to voice their community-related aspirations and concerns.

The Office of Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas of Los Angeles County was sufficiently impressed with the creative approach to urban planning outlined in the book that it requested similar approaches for five other unincorporated communities. One of the challenges the team encountered was with the scheduling. As Ivins put it, “the project team realized that the work of entering a community, building trust and on the ground partners, takes time.”

Inspired by the work in Willowbrook? Connect with neighbors and work on your own community vision with The Road to a Community Plan or share what’s special about your neighborhoods with the Neighborhood Postcard Project, available on Creative Exchange’s Toolkits page!