What does it mean to be Black? “The ‘Black Card’ Project” explores ideas around Black identity and belonging

Dominic Moore-Dunson says he was one of the rare boys who started dancing when he was just three years old.

“I was a little hyper. I had so much energy. My mom was like, ‘Let’s put some tap shoes on this one and hopefully he’ll come home tired,'” he laughs. His older sister was also in dance class and he just wanted to follow her around all the time anyway, so he was happy to go off to class with her. He kept at it because she kept at it, until finally, in middle school, he realized he actually liked it.

Moore-Dunson continued to dance through high school at the performing arts school within Firestone High School in Akron, Ohio, where the emphasis was very much about learning choreography and being a maker. He was also a big soccer player, and when he attended the University of Akron after high school he continued to both play soccer and dance. But UA is a top three school in Division I soccer—for the other guys on the team, soccer was serious; it was a job. He just didn’t care about it in the same way that they did—but he did care about dance that way.

He also wanted to actually dance somewhere rather than study it in school; his experience studying choreography and creating dance in high school instilled in him the desire to be a maker rather than a student. He remembers being in his then-girlfriend/now-wife’s dorm room about to go to ballet class and saying, “I think I’m done with this whole class thing.”

And that was that. It was the middle of the school semester and he just left. He went online to look for cities where he might be able to train, looking at the obvious ones like New York and Los Angeles, then on a whim he figured he might as well also look at Cleveland because there would be fewer obstacles to getting in and he wouldn’t even have to move.

That’s when he first discovered Inlet Dance Theatre. It wasn’t ballet but contemporary dance, which he thought was awesome. Within a few days he was at the studio checking it out, and he liked it so much he said, “I’m staying here.” That was ten years ago now.

Moore-Dunson is now assistant to artistic director Bill Wade as well as a company member of Inlet Dance Theatre. Founded by Wade in 2001, who had previously developed the nationally acclaimed after-school dance program “Youth At Risk Dancing” (YARD) while at the Cleveland School of the Arts, Inlet advances his mission of using dance to further people rather than using people to further the agenda of dance. “He’s equally interested not just training us as dancers but in mentoring us as makers and educators,” Moore-Dunson says.

Inlet is known for their Summer Dance Intensives (SDIs), a four-to-six-week intensive program for dancers ages 16 and up (there is also a SDI Jr program for ages 6-11) where the emphasis is as much on personal development and character growth as it is on dance technique. For three years Moore-Dunson choreographed the men’s programs for the SDIs with Wade mentoring him. Wade then asked for his help on Inlet’s training and pre-professional programs. A quartet Moore-Dunson created in 2017 became the first piece of company repertory created by a company member. At the same time, he was also working on a personal project with collaborator and fellow Inlet company member Kevin Parker called “The ‘Black Card’ Project.”

If you’ve read this far, then you have gathered that Moore-Dunson is a cisgender heterosexual Black male. None of these aspects of his identity have anything to do with his interest or ability in dance, and are themselves only remarkable in the context of him being a dancer in that other people—informed by social stereotypes and prejudices—make them so. This understanding was the seed of his idea for “The ‘Black Card’ Project,” a piece of live-action dance theatre that explores ideas around Black identity, perseverance, and belonging.

Moore-Dunson grew up in Akron’s eastside in Joy Park in the ’90s when Black gang violence was at an all-time high throughout the country. “Akron was no different,” he says, “so that was the world my sister and I grew up in.”

But, he says, their mom was in the Air Force so they grew up with an understanding that they could be anything they wanted to be in the entire world because the entire world was only a plane ride away. But the moment he stepped foot outside his house, that stopped being true: the general consensus was that people don’t “get out” of the place where he grew up.

He remembers the exact moment when he realized his identity as a dancer was at odds with his identity as a young Black man. He was hanging out with a group of other Black boys in his grade and they were all talking about what they wanted to be when they grew up. “I want to be like LeBron,” several of them said. Moore-Dunson had athletic accomplishment on his brain, too, and he shared that he either wanted to dance in Paris or play professional soccer in England.

“The table got dead silent and my friend said, ‘Dom, that ain’t Black.’ The table erupted in laughter,” he recalls. “That was the first time I realized that the color of my skin and my professional aspirations had anything to do with each other. To hear it from someone who looked like me was really difficult to deal with.”

He spent the rest of his adolescence hiding the fact that he continued dancing and playing soccer. He realized he didn’t fit in with the other Black kids, so to compensate for that he started running track and field—a “Black” sport. As an athlete who had spent most of his life in some form of training, he quickly excelled in this new sport, becoming the third-ranked hurdler in the state of Ohio. And, all of a sudden, he became really popular within the school’s Black community.

“I ran track and field to get ‘Black’ points and it worked,” he says. “I was Black every spring!”

In 2015, as more and more national news and conversations came to be about unarmed Black men being killed, he remembers seeing his own social media feeds filled with condolences and memorials: “rest in peace” so-and-so, “remember” so-and-so. They were people he had gone to school with. Some of those boys who wanted to be like LeBron had ended up in jail; others dead.

He remembered his experience in school of being really interested in the lives of those around him and how different theirs were from his, even though they went to the same school. Firestone was a public school with a performing arts inside of it; he attended the performing arts school, a place many parents (still) send their children to get them out of the “normal” public schools and the problems that plagued them, and also to give their kids better opportunities. He may have gone to school in the same building as those other boys, but they did not live the same lives.

He knew he wanted to do something, but all he knew how to do was dance and make dance. So he decided to do what he knew, starting with the question, “What if someone had to go to school to learn how to be Black?”

He then asked Parker, the other Black male in the company at Inlet, “What does it feel like to have someone tell you you’re not Black?” From there, the two began collaborating on “The ‘Black Card’ Project.”

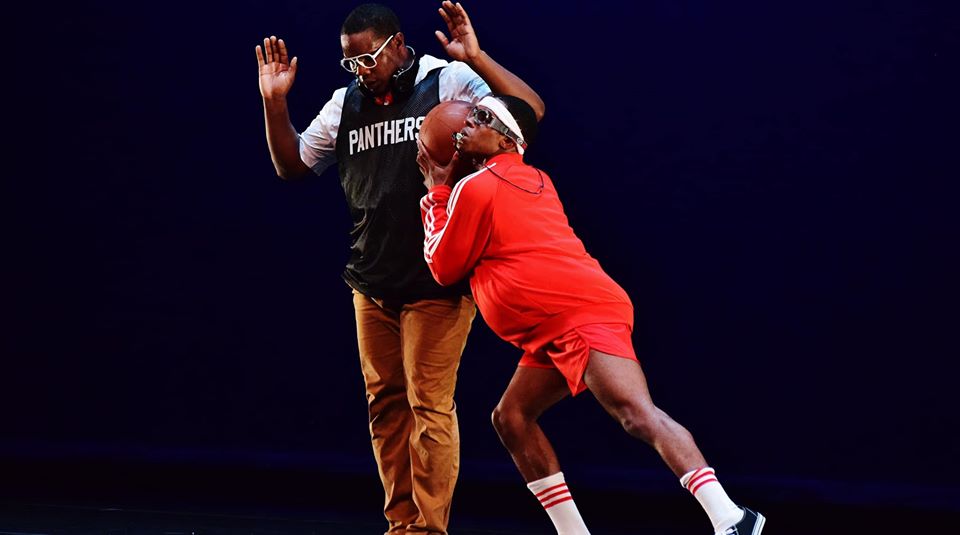

“The ‘Black Card’ Project” is a family-friendly show aimed at students in grades 6-12. It is the story of Artie Alvin Beatty III, a home-schooled Black boy who loves to talk to his imaginary friend and has a rich inner world. His mom is concerned about his lack of awareness of his cultural identity, so she sends him off to the Booker T. Malcolm Luther Parks Academy of Absolute Blackness, where he has to pass classes on Blackness such as “How to Dance On-Beat” and “Thuggin’ 101” in order to earn his “Black card,” a metaphor for a person’s Black identity, authenticity, or belonging.

“If you’re teaching young Black boys that they can be a baller, a rapper, or a thug, that’s going to limit their economic opportunities substantially,” Moore-Dunson says. “If we can open up a conversation about how narrow this Black identity is, it can also help in Black economic development.”

He explains that both he and Parker feel strongly that the economic piece is a symptom and not the root issue; the root issue, he says, concerns identity, and how people perceive themselves and their community (and why). In his own experience, older generations of Black Americans show concerns when a young Black person—like himself—wants to work in a job or industry that stereotypically doesn’t employ a lot of Black people. These elders aren’t trying to keep the younger generations “down;” they’re just concerned for the safety of these young Black men and women being out in the white world. And they certainly have plenty of reason for that concern.

“This show is about creating this multi-generational perspective,” Moore-Dunson says. “Neither grandmother nor grandson is wrong. Every time I talk to my grandmother she always asks me how many Blacks were in whatever place that I was. She experienced the race riots in Kent where white people burned down the Black neighborhood, so she’s very concerned all the time.”

Part of what the show is about is showing the complexity of Black identity: “As many Black people as there in this country and in the world, that’s how many ways there are to be Black. As a minority group, one of us represents all of us. And it’s a beautiful thing. But it does not make us a monolith culture.”

“The ‘Black Card’ Project” deals with thought-provoking and challenging subject manner, but it is also a comedy that incorporates elements of ’90s sitcoms and variety shows (as a child of the ’90s, Moore-Dunson grew up when shows like Family Matters and In Living Color were hugely popular prime time television that prominently, if not exclusively, featured Black actors and characters in family-friendly sitcom situations and SNL-style sketch comedy). It also draws a lot from the Saturday morning cartoons he grew up with.

“We found a way to fool people into our world to have these difficult conversations,” he laughs.

While creating the show, Moore-Dunson got to return to his middle and high schools and worked with students there to help him and Parker create different sections of the show.

“There are movements in sections of the show that were made by sixth-graders and high school kids that Kevin and I perform to get them to realize that their voices matter in this much greater conversation,” he says. “The kids were so excited to see their work in the show. The idea for it was to really be community-based. Yes, it’s my story, but we wanted to make sure it wasn’t just our big fat opinion of what Blackness is so we did a lot of research. It’s a composite of many ideas of Blackness in the community.”

“The ‘Black Card’ Project” first premiered at Firestone High School in 2018 to 800 students from all over Akron and Cleveland. Moore-Dunson and Parker, the sole performers of the show, have also performed the show at the Akron Civic Center and developed a movement workshop based on the show for students that they’ve taken into schools. During these workshops they talk to the students about identity, collaboration, leadership, resiliency, and how all of those things work together to affect them personally and also economically.

“The idea is to start the conversation early about how economics matters and this is why, this is what it actually means, and this is why your identity is important in relation to it,” Moore-Dunson says.

He says feedback has been “all over the map,” but primarily in a positive way. “Some Black people are like, ‘Yo, you’re letting out all our secrets,” he laughs, “but others say this is a source of inspiration to them and it has helped them realize it’s okay for them to talk about their Blackness out loud.”

And while “The ‘Black Card’ Project” is explicitly about Black identity, its themes of belonging and limiting identities resonate with audiences, especially kids in their target demographic of grades 6-12, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

“We’re talking about the Black experience because that’s what I experienced, but this thing is universal and you can feel it in all kinds of ways,” says Moore-Dunson. “We always ask the students afterwards, ‘What did the show do for you or not do for you? Even if you’re not Black, what parts of your life have been narrowed by the people around you?'”

At the time of initial shutdowns due to COVID-19, Moore-Dunson and Parker were in the middle of phase two of the project, working to get the show into all of Akron’s public high schools and also working with a nationally renowned booking agent to book shows throughout the country, as there is quite a bit of national interest in the show. As so many other performing arts organizations and projects have had to do in response to the pandemic, they have had to cancel all performances and reconsider what they’re doing with the project from this point forward.

They were already thinking a lot about creating an online platform to host digital content—they have a YouTube channel for the show already—so they can reach exponentially more students throughout the country. Logistically, even absent a global pandemic, they can’t be all over the country at the same time, but they can create more content so that the conversation can continue online. In addition to that, they had also been working on a 90-minute documentary on the show with a producer from PBS Western Reserve.

For Moore-Dunson, the key is to create content that continues to engage people in various ways, and also to make sure that what they’re creating continues to be of value to people. He would like to create short videos, about two to three minutes each, breaking down various pieces of the show and why those pieces are relevant to the limiting aspects of “Black identity,” so people are able to frame what they’re seeing in the show before they see it. “The fact that it’s about Blackness makes people nervous,” he explains. “If we have these videos and break it all down for people they’ll say, ‘Oh, I get it now, there’s nothing scary about the show.”

All photos from “The ‘Black Card’ Project,” courtesy of Dominic Moore-Dunson.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I LOVE the idea of getting everybody either in the room or at the table really early if possible—throwing out the idea and watching the idea form itself. I love the idea of working like a composer: give them the idea I’m working with, let them work, and let their idea of the music change the way I’m working on the piece. There’s an intersection where everyone is working in this flow state together. It’s hard to get that early in the process but it’s super fun to do.

(2) How do you start a project?

I always start a project based on something I have been thinking about and researching for six to eight months before ever even walking into the studio. My starting place is at home on the computer or buried in a book, and then when I get into the studio I basically make a bunch of stuff—like throwing paint on the wall. I get it out of my body and brain, look at the paint on the wall, and rip that sheet of paper off. Then I know which direction to be going. I see what comes out and go from there.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

I see the value that I have is in the value I can bring to others. I’ve been talking about this subject a lot lately: am I, or how am I, bringing value to people. Intrinsically, whether good, bad, or indifferent, I understand my own value and I am okay with that. I don’t have to explain it to others because I know I have value myself, so if that’s okay then how do I use that to bring value to other people, like approaching the Akron Chamber and saying, “This is how I think I can bring value to you and what you’re trying to do here.” And the way you talk about value changes depending on who you’re talking to. If you want to talk about your value as an artist, it’s important to understand the many different types of people you’re going to be discussing your value with and be able to explain how what you do is valuable to health and medicine, transportation, or arts. Then you can use different language to talk about your value to them regardless of what sector they’re in.

(4) How do you define success?

This has changed for me. Success used to be so much about my professional life, but in the last two years I got married and am having a baby in August. Suddenly that changes your idea of success! For me, success is really about balance, I’m finding. Professionally, doing the things I’m excited about, working with people and doing projects I’m excited about, exploring new paths and doing things I’ve never done—the process feels like success to me, as opposed to the end point or product. It’s also about making sure my family life is good, that I’m raising a child who is healthy and our family life is fun and adventurous. Also, learning what it is to have a hobby; that is, to do a thing that has no intrinsic monetary value to it—just a thing you love to do. Success for me is finding that balance.

(5) How do you fund your work?

The way we fund this work (“The ‘Black Card’ Project”) is through the Knight Arts Challenge, but it’s also super important to have individual donors. Local foundation support is also a big one. The one thing often missed by nonprofits is finding new streams of earning revenue. Obviously the ecosystem works with foundations and I love it, but it’s equally important for artists to think about what it means to have business-to-business revenue, and what it means to have a business as an artist and taking your work straight to customers.

We have event services where we take our repertory, break it down in different ways, and perform pieces at large corporate parties, like maybe having a moving sculpture in the middle of a large gala, so that’s a different revenue stream for us. But we’re in this time where everything is shutting down [editor’s note: this conversation happened in early March as shutdowns were just starting], so how do we as makers, artists, and arts organizations create revenue streams where we are not dependent on foundations or on audiences having to be in the audience?

I have some friends who are musicians and they play jazz clubs, but the jazz clubs take a cut of the door and the musicians are only paid through the clubs. What is it for a musician to go straight to the customers outside of the jazz club instead? Now we’re spending real time thinking about that, and it is going to open up avenues for artists we have never thought about before.