Urban Matter Inc. creates interactive installations that combine technology, design, and community

This story is supported by a National Endowment for the Arts Our Town Knowledge Building grant supporting a partnership between Springboard for the Arts and the International Downtown Association. See more stories from the partnership here.

Shagun Singh is a co-founder and principal of Brooklyn-based Urban Matter Inc., an interdisciplinary experience design studio that tells stories, visualizes information, and inspires interaction through the intersection of technology, design, and community.

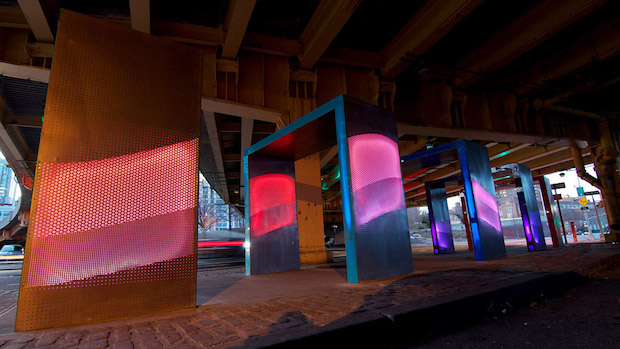

Basically, they design really cool interactive multi-media installations that serve educational and engagement purposes for nonprofit and government clients all over the country, and it all started back in 2013 with an installation under a highway overpass called Silent Lights that almost never saw the light of day (or night, as it were).

Singh earned an undergraduate degree in architecture in India and moved to the United States 12 years ago to pursue a degree in interactive telecommunications at NYU.

“I was very interested in how architecture, or art, meets technology,” she says. “I’ve always been interested in how these two disciplines come together.”

She worked at an architecture firm right after graduating from NYU, where she got involved with Architecture for Humanity, a San Francisco-based nonprofit design services firm with a global network of architects who wanted to work on socially responsible projects. It had a small studio in New York dedicated entirely to local projects. (The organization has since ceased operations.)

While Singh worked with the group, they did a project called ARTfarm with the New York State Department of Transportation and the Bronx Museum of the Arts, a floating urban garden next to the museum funded by an urban arts grant available through the DOT as well as a small Kickstarter campaign. This was during the recession when many architects were losing their jobs; as a result, many were looking for more work in that socially responsible realm. Through the connections formed through Architecture for Humanity New York, Singh and other architects formed the Artist Build Collaborative.

This new collaborative applied for another project through the DOT – a creative intervention at a busy underpass in Brooklyn that was actively used by people passing to and from the Red Hook and Gowanus neighborhoods to get to the train station. Like all highway underpasses, this one was noisy, dirty, and dark – not exactly what you might envision as a potential place for vibrant, creative community engagement.

“We thought it was interesting because there is absolutely nothing artistic about that neighborhood or site,” says Singh. “”It was just a place where you would not envision art; but it’s a very busy, very important throughway.”

The collaborative developed an idea for an interactive LED installation that responded to sound, consisting of five multicolored gates that light up sequentially in response to ambient noise. The DOT loved it and made $5,000 available to the collaborative to fund it.

There was just one problem.

“The design was a lot more ambitious than the budget that was made available to us,” says Singh. “This was very clearly a $50,000 project, ten times more than what we had. With ARTfarm we had a similar problem but we didn’t have as much to raise to make up the difference.”

They tried the Kickstarter strategy again, but the project was simply too big to fund that way. So they reached out to nonprofit organizations within the community, forming connections that ultimately helped fund a part of project.

But they still weren’t there yet.

The DOT awarded them the project in 2011. In 2012 they were fundraising within the Gowanus and Red Hook communities, including a huge fundraiser in an industrial space where they were able to raise another $5,000, which was then enough for them to create a prototype to take to other funders. The Black Rock Foundation kicked in $6,000; they also got grants from Designers Lighting Forum of New York, the Brooklyn Arts Council, and the Awesome Foundation.

It was finally a $33,000 grant from ArtPlace America in 2013 that put them over the top for this project that ended up costing $75,000. Finally this thing was funded and they could get to work, after two years of community-level grassroots funding efforts.

They got all their resources together, got a studio space near the installation site, lined up local people to do the installation work…only to find out that the underpass they had selected had recently gone under major construction that was scheduled to last two years.

If right now you are thinking to yourself, “But wait: doesn’t the Department of Transportation oversee all construction projects?” Why yes. Yes it does. “And wasn’t this a Department of Transportation project?” Indeed it was. “So wouldn’t they have known about this project that was in the works?” In theory! But the project was overseen by the DOT’s Urban Arts Program, and the separate departments within the DOT function independently; one hand doesn’t know what the other is doing.

So the DOT told Singh and her group to pick another site.

Through partnering with the Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership, they ended up at a new site relatively close to the original, at the intersection of six different neighborhoods in northern Fort Greene, Brooklyn. Singh says this site wasn’t quite as “deserted” as the previous one – it had a community around it with a large housing complex, a school, and a park.

“It was a lot more communal,” she says. “When we installed the project there was so much interest in it. It’s the kind of a neighborhood where people don’t expect to see art.”

Adjacent to the hip, artistic Dumbo neighborhood, Singh recalls people asking her why they weren’t installing the project there instead. “You’re in the wrong neighborhood,” people would tell her. “No one is going to appreciate it there. Why are you wasting your time?”

But on the very first day it went live in December 2013, Singh says there was an “enormous number” of people who stopped by – kids going to school, people going to the park, police officers, makers interested in the technological aspects of the project; lots and lots of people came to check it out.

“Kids were screaming at it to make the lights light up,” Singh recalls. “Cops were trying to trigger it with their sirens. It just had this excited reaction with everyone.”

Silent Lights used 2,400 multi-colored LED lights to transform the irritating, ever-present traffic sounds into a tangible, reactive presence that offered a bit of respite from the noise, while also providing an additional element of safety in the dark, gloomy underpass during the hours when the street lights weren’t on, and eliminate some of the broken glass syndrome endemic to such semi-secluded areas.

“The thinking around the piece was that it converted this really loud noise and traffic into light animation, taking something which was really negative and making it into something that was positive that provides security, delight, and a certain level of conversation material,” says Singh.

The installation stayed up for two years, during which time the collaborative became Urban Matter Inc. In 2015 they made the choice to take it down, despite how much people wanted to see it stay permanently.

“It was meant as a temporary piece,” Singh explains. “We didn’t want it to start deteriorating and become a piece of rubble. In six months it would have started to show its age. We really wish we could replace it, but it was an expensive piece!”

Silent Lights caught a lot of people’s attention, and not just the people who went by the underpass. Urban Matter Inc. was asked to speak about the project at a school where the kids treated them like they were celebrities.

“It was really touching and fun,” Singh says. “It was so intimately involved in their everyday lives. I have cards from kids that say how they were inspired by it and it made them want to become inventors. That was something I didn’t envision, and the new site helped because it was close to a schools so it attracted kids.”

They were also approached by other organizations to recreate the project, but, Singh says, they never really looked at making it scalable or replicable. “That’s kind of what our work is about – creating these temporary pieces in these specific places.”

Multi-disciplinary creative intervention work is now the calling card of Urban Matter Inc. Singh and her co-founder and fellow principal Rick Lin, an artist and creative technologist, formalized the organization as Urban Matter Inc. in 2014 after the installation of Silent Lights, transitioning it into a more “legitimate business framework” and primarily working on artistic interventions with nonprofit organizations and governments. They provide strategic overview, concept development, physical design, and content and technical development services. Industrial designer Marcel Marquez and architectural designer Heeju Choi round out the team.

Singh says they have the capacity to work on about three projects per year. Since Silent Lights, they have installed a light installation in an empty storefront in downtown Brooklyn – an interactive game of Pong controlled by smartphones that transformed a vacant, negative space into something engaging.

“How do you take these spaces that are unused and create an engagement for even a week?” Singh asks. “The Pong game was up for two weeks and it was a huge success. It just changed the dynamic of the space so much, changing that area for the better. Our agenda is around finding these really interesting opportunities and creating them for a specific period of time.”

They did another interactive project in Louisville. This was initiated by Creative Commons, which wanted to create an artistic intervention around air pollution in Louisville, the city with the worst air pollution in the United States.

When Urban Matter Inc. held a community workshop to engage the community and get them involved in the creative process, they found out that the people definitely cared about air pollution but, as one attendee noted, once everyone went home from the workshop, air pollution wouldn’t necessarily be at the front and center of anyone’s lives because it is an invisible problem.

So, Urban Matter Inc. made the invisible visible, creating a huge interactive screen on which air pollutants were represented as floating particles that people then popped, like a video game. With every popped particle, viewers got a tip on how they can do something to mitigate air pollution. That project has since been purchased by the Institute for Healthy Air, Water, and Soil in Louisville and adjustments were made to make it a traveling exhibit for school children.

The Urban Matter Inc. team likes the idea of these “guerilla”-style opportunities, seeing the community’s reaction and then moving on, but as the company evolves so too do the projects. They recently finished their first permanent piece called Golden Afternoon, a public-private partnership between the City of Austin and private developers located in a parking garage in Austin.

“A parking lot is a really interesting space where people don’t expect to engage with art,” Singh says. “It’s not a place where you make friends and expect to engage in conversation with a stranger.”

The Austin project features a stairway that lights up when someone walks on it, immediately catching the attention of anyone nearby and sparking conversation about it. “It’s interesting to see strangers talk to each other. We want that. We want people to get to know each other in the places they go every day.”

Next on their agenda is a collaborative project with some filmmakers in New York. Urban Matter Inc. is creating the “physical envelope” of a booth in which people will be filmed giving their confessions…to AI. This booth will look like a “small, futuristic chapel” and will travel to six different neighborhoods in New York this May.

While there has been some corporate interest in their work, Singh says they have yet to really pursue that option. “It doesn’t drive us,” she explains. “Community is a huge factor in everything we do. We’re not opposed to corporate work but we have to be careful who we pick and what their agenda is because community is very important.”