Rivers Run Through It: Shel Neymark’s Mural Map & Community History Project in Rural New Mexico

Shel Neymark was born and raised in Chicago, near Oak Park. He remembers there were 52 Frank Lloyd Wright houses within biking distance of where he lived as a kid and he was “fascinated” by them.

“I would ride around and sneak into people’s backyards,” he recalls. “That was a really big influence on my interest in art and architecture.”

Neymark is a ceramic artist, and has done “architectural ceramics” for most of his life—tile work, murals, custom sinks, etc. He also does pottery and sculpture, and more recently has been working with glass, but the architectural ceramic work is what has primarily sustained him.

After graduating from Washington University in St. Louis with a degree in ceramics in 1974, Neymark moved to Missouri where he taught ceramics at the University of Missouri Craft Studio. He also plays violin, and was in several area bands. A band mate from one of those bands moved to Santa Fe and told the other members that he had plenty of gigs for them; they just had to move to Santa Fe, too. So Neymark loaded up his Volkswagen van and moved to Santa Fe on a whim, a place he had never even visited before, in 1976.

“Everything fell into place for me there,” he says. “We had lots of music gigs. I found a shared studio right away. It just felt like a good fit for me there in the art community.”

But even in 1976, it was already difficult for an artist to buy a house in Santa Fe. A few years after he moved, he bought some land about an hour north of the city in Embudo, New Mexico, a village where some of his artist friends also lived. He and his wife Liz still live there to this day, and he often canoes to and from his home and studio rather than travel down the two-mile-long dirt road.

“There are a lot of artists here. I think a lot of hippies moved here in the ’60s because land was cheap in those days,” he laughs.

The current population of Embudo is 454; the neighboring town of Dixon, where Neymark has done a great deal of community-building work for which he has been honored, is about 847.

Neymark absolutely adores it. Dixon is located on the Embudo River, which flows into the Rio Grande, and Embudo is located on the Rio Grande. The area is physically beautiful: a lush, green river valley full of rich farmland, surrounded by 13,000-foot peaks and dramatic mesas.

“On so many levels, this is a magical place to be for me,” he says. “It really worked out! Politically, being kind of a socialist radical is the norm here, so I feel really comfortable in that way, too, though maybe I’m in some kind of a bubble. There are artists and writers and farmers and builders here, and it’s great!”

Building a Library

In the late ’80s, some friends of his in Dixon casually mentioned, “Wouldn’t it be great if we had a library here?” Neymark certainly thought so; at the time, Dixon was a struggling city but it had always been “a wonderful community.” The local bar was closing, and that had always been the local gathering place (it’s where Neymark met Liz). The general store was closing. The gas station had already closed. It was becoming a bedroom community with no businesses, and yet it was still full of artists—the annual Dixon Studio Tour of artists’ studios, always held the first weekend of November, had already been running successfully for several years and is now one of the oldest continuously run studio tours in the state, bringing in thousands of people each year.

Neymark and his fellow citizens felt that a library could be a community center and gathering place for the whole Embudo Valley and beyond.

“We just felt like we needed something like that here,” he said. “There were a core group of about eight people who would gather once a month and say, ‘Okay, how are we going to start a library?'”

They found a place to rent for $200 a month. They didn’t know how they would get the rent money but they jumped in and rented in anyway. Then an article ran in a Santa Fe newspaper about this group trying to start a library in Dixon, and book donations started pouring in. “Suddenly we were to the ceiling with books!” A volunteer who had studied library sciences stepped in and helped organize the whole thing, and the Embudo Valley Library & Community Center opened in May 1992.

They found a place to rent for $200 a month. They didn’t know how they would get the rent money but they jumped in and rented in anyway. Then an article ran in a Santa Fe newspaper about this group trying to start a library in Dixon, and book donations started pouring in. “Suddenly we were to the ceiling with books!” A volunteer who had studied library sciences stepped in and helped organize the whole thing, and the Embudo Valley Library & Community Center opened in May 1992.

“We had no idea if it would be successful or not or if people would even use it,” Neymark recalls. “But from the very start, it was wildly successful.”

In the first few years, the library introduced children’s programming and started hosting author readings and events in the evenings. Neymark started as treasurer and then learned how to write grants, which allowed the library to actually hire librarians (all were volunteers initially). After 10 years it became obvious they had outgrown their rented space and wanted a space of their own. The general store had been closed for over a decade by then, so they set their sights on purchasing the building. A generous donor in the community offered them $200,000 if they could raise $50,000 on their own; they managed to raise it in six weeks.

“In this very poor community people were pledging $500 when I knew they couldn’t even buy their groceries,” Neymark says, underscoring just how much this library meant to the community. Two months after they decided to buy the property, they moved in. The acre-and-a-half parcel of land included the old general store with and an Arts and Crafts-style house. The general store was used as the community center and the house as the library.

After a couple of years some folks in the community got together and said they wanted to start a food co-op. Dixon didn’t have a single grocery store, and even the general store (back when it was open) had only sold things like chips and canned goods. So the library leased out two-thirds of the general store building to the Dixon Cooperative Market in 2005, and it has thrived ever since.

“The first time I walked in and saw organic broccoli I was almost in tears,” Neymark laughs.

The library ultimately wanted to build a new building next to the Arts and Crafts house, and in 2014 they were able to move into their brand-new, 3,000-square-foot space, renting the remainder of the general store to the co-op.

Today the library serves about 8,500 people in rural communities spanning from Taos to Española, offering 15,000 books, movies, and audio books; public access computers with Wi-Fi; print, copy, fax, and notary services; a variety of children’s educational program including a “fabulous” STEM program in partnership with Northern New Mexico College and a 3D printing and robotics program; a low-frequency radio station; a weekly farmers market in the summer; a heritage orchard with heirloom apples; a park; and a community center that is free to use.

The impact of the library’s educational programs cannot be overstated: In a state that performs notoriously low on student test scores—20 percent math proficiency statewide, and 17 percent in the Rio Arriba County, which encompasses Dixon and Embudo—students in the fourth grade class at Dixon Elementary School, which the library has partnered with, are testing at over 90 percent math proficiency.

The library has won several awards over the years for its work in civil service and community engagement, including most recently the Institute of Museum and Library Services‘ National Medal for Museum and Library Service in 2015, for which they got to travel to the White House and receive the award from Michelle Obama.

“They gave us this award because we do incredible work,” Neymark says. “We’re just really a vibrant organization. This library has transformed the community. There is so much cohesiveness here that just wasn’t here before it opened, and part of that was creating spaces for people to gather.”

Mapping Local History

For him, the Mural Map & Community History project was a very logical next step because people were interested in the history of the area.

He had done a few ceramic-based public art projects throughout New Mexico previously, several of which involved a fair amount of historical research and all of them involving the design of public spaces. He always thought it was unfortunate that unincorporated communities, like Dixon and Embudo, never really get the chance to have public art funded by major granting agencies because these things tend to be tied to infrastructure that unincorporated communities simply don’t have.

“I thought it would be really great to do something in my own hometown,” he says. He thought about the area’s acequias—communal irrigation canals designed to preserve and share scarce desert water throughout New Mexico. The acequia design in Spanish is origin, and some of the acequias in New Mexico are more than 300 years old, initially built by Spanish colonists. Not only are they important to the area’s agricultural history (still to this day), but they are also an important part of the area’s cultural history and heritage, too: Hispanos comprise more than 70 percent of the population of Rio Arriba County, with many families having roots in the area going back several generations.

“I thought it would be really great to do something in my own hometown,” he says. He thought about the area’s acequias—communal irrigation canals designed to preserve and share scarce desert water throughout New Mexico. The acequia design in Spanish is origin, and some of the acequias in New Mexico are more than 300 years old, initially built by Spanish colonists. Not only are they important to the area’s agricultural history (still to this day), but they are also an important part of the area’s cultural history and heritage, too: Hispanos comprise more than 70 percent of the population of Rio Arriba County, with many families having roots in the area going back several generations.

“I started thinking about our acequias and how they would look [in a mural], just this little channel of water,” he says. “There are these wonderful, gorgeous microclimates that happen around the acequias. I just wanted to see what the pattern of them would look like. I thought the way they follow the contours of the hills would make beautiful lines. And of course they’re really important to the history of the valley, but part of this idea came about just from aesthetic curiosity.”

The Mural Map & Community History project was born out of the combination of Neymark’s desire to create a public art project in Dixon, the historical and educational aspects of it tying into the library’s own mission, and its potential to serve as a focal point in a public place where the community can gather.

“Any way that we can do community building just makes us stronger; it makes us face the issues we have here because are getting together and talking about them,” Neymark says. “I’ve always felt public space are an opportunity for people to interact with each other.”

He partnered with local historian and author Estevan Arellano on the project. Arellano was a huge advocate of the acequias and acequia culture (which has a lot to do with community cooperation and collective action; it is a culture that has been dying out in recent decades) and had even written a book on those in the area. He was also interested in ancient place names and thought that the ancient Spanish names were being lost, so he advocated for place names being part of mural. They would see each other around town and talk about their ideas for this mural, and as it coalesced Neymark said, “Okay, let’s do it, I’ll get you some money and we’ll work with teens because they’re the future of this place.”

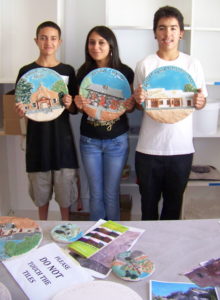

Neymark was good on his word and they were able to hire on four at-risk local teens for nearly a year to assist with the research, design, creation, and installation of the ceramic mural map. The 40-foot mural was placed on an exterior wall of the co-op in July 2015, and the little alley that the wall faces was transformed into an outdoor gathering place with plenty of picnic tables and the mural as the focal point.

“It deepens a sense of place for local inhabitants and visitors,” Neymark wrote in his initial response to Springboard’s call for rural arts toolkits. “Every place humans live has a rich history and unique sites. The more you know about the place you live, the stronger your connection. As rural towns lose population and struggle economically, that sense of connection particularly important and impels people to stay and work on making their towns more viable. Local gathering places where people connect, and perhaps share food, strengthens a sense of community and fosters interpersonal relationships. This is particularly important in small towns where there are few services and people have to take care of each other.”

Sadly, Arellano didn’t live to see it completed; he passed away in October 2014, three months into the project. He had already written down the names of the places and had spoken with the teens a few times already, sharing the stories of the various places of historical importance around town. Neymark has fond memories of the man, with whom he had become very close friends over the years. “I respected him incredibly.”

On the Brain

With the mural map completed, Neymark is interested in creating more public art pieces and sculptures. He has most recently been interested in the human body, and especially the brain. He has made several interactive sculptural pieces in partnership with an engineer friend of his that explore ideas around the human brain and how it functions.

“I think the brain is a fascinating organ; it’s so complex and mysterious,” he says. “What is the relationship between who we are and our brains? Are we our brains? Are we how we control our brains? I feel like as I’m getting older—I’m going to be 68 soon—that I might as well explore the difficult questions like, ‘What is life? What’s the point of all of this? What’s the mystery of life?’ Understanding what our own brains are is one of the things we least understand. We’re learning a lot about how neurotransmitters work and how synapses fire off and where thoughts develop, but actual consciousness and what drives it all—we don’t know anything about it.”

One interactive sculpture called “Brain Waves” involved putting a band with electrodes on a person’s head, measuring their alpha waves that would manifest as drops of water in a pool. Another called “Heart Drum” involved a sensor on a person’s ear that would play bass and snare drums in rhythm with their heartbeat. He included a pair of bongo drums so people could play along with their own heartbeats. “You have to pay attention to your own internal rhythm in order to play a duet with yourself because your heartbeat always changing.”

He has a few more brain-related pieces he wants to create: some wordplay pieces on “brain cell” and “synapse/sin apps,” and an interactive piece called “Synesthesia” that will translate sound into color.

Additionally, Neymark still plays in bands. The one he plays in now is called the Placebo Effect, and they play jazz, old standards, and a little bebop.

Neymark loves his community and loves that he is able to make a tangible impact through his various projects.

“If I had stayed in Santa Fe I don’t think I could have had the kind of impact on my community as I had here,” he reflects. “In a small community you can make an impact in a way that’s really gratifying.”

“It’s not perfect,” he continues. “There are problems here, just like everywhere else. But it’s kind of nice walking into the post office and the co-op and knowing everybody there. I like that. I find that to be really rich. I’ve been here 35 years and have been coming here for 40 years. I feel like I’ve been to so many weddings and funerals I could never leave these deep connections. Being part of that is so rich. The people here are so interesting. I’m so lucky to have found this community.”

Get the Mural Map & Community History Toolkit here: https://springboardexchange.org/mural-map-community-history-toolkit/

All photos provided by Shel Neymark.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

When I’m making a piece, I like to be the one who is designing it. I like for it to be my piece and I will take input from people and consider it, and even solicit input, but I like to be the boss on my artwork.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I’m lucky in that I always have inspiration. Ideas just come from different places, and they always seem to come to me, so I’m fortunate in that. I hike every day, so once an idea comes to my head, usually when I’m hiking, I just kind of roll it around in my head and think about how I want to do it. Sometimes I’ll think about it for years before I actually do it; sometimes I’ll go into my studio and start on it the next day.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

For me the biggest value is that I get to create to live. In my life, I’ve never had a job outside of my art. I get to do whatever I want all the time. That is a huge value to me; it’s much more valuable than money, although like everybody else in society I need money to pay my electric bill. Looking at the kind of money I make and that most other artists make, I wish artists were paid more like professionals in society, but that’s just not the way it works. That’s capitalism. But I do consider myself a professional.

(4) How do you define success?

There are so many different levels to that. Getting something out of the kiln that’s just so beautiful I can’t stop staring at it; that’s success. Going to the co-op and seeing a bunch of people studying the map and pointing out different sites; that’s success. I don’t make a lot of money, but as far as in my life, I have to be one of the top .0001% happiest and luckiest people in the world, and I would say that’s a definition of success!

(5) How do you fund your work?

I have a pretty simple life. I don’t require lots of stuff. I’ve owned my house and land for 20 years so I don’t have a mortgage. I have enough to buy all the organic food I want. I have a really good life. I get to travel. We have solar heat in the floor so we have no heat bill. We have a well so there’s no water bill. Because my expenses are low, when I make money, I’m able put it back into my work. I do commissioned work, and that has really sustained me—sinks, tiles, light fixtures. Then after I do that, I get to sit in my studio and make a sculpture, and when I sell that one, I say, “Okay, great, now I get to make two more.”