Connecting creative practice to healthcare through Ready Go tools at the People’s Center Health Services

Amid all the uncertainty around health insurance, the fact remains that people need access to healthcare. Clinics and healthcare systems around the country have been seeking new and innovative ways to improve care, from electronic medical records, to searching for trends in big data, to remote or online diagnostics. But the benefits of in-person care and building ongoing relationships, can’t be understated, from early detection of issues to long-term cost control. To help with these efforts, one clinic in Minneapolis is turning to the arts.

This summer, Springboard for the Arts has partnered with the People’s Center Health Services to have Ready Go mobile artists’ tools out in front of their clinic in Minneapolis nearly every Thursday. The projects, selected from a number of different available Ready Go tools, are intended to draw attention to the clinic and spark conversation about healthcare needs.

One such project, sPARKit, appeared three times through June and July, making it the most frequently reappearing project of the summer. sPARKit artist Soozin Hirschmugl has a background in social work as well as art and says she is always thinking about issues of community health from a social perspective, but also from an artist’s perspective.

“When those two things combine, it kind of looks like public health, and how people use green spaces and why they are important,” she explains. “This was a great opportunity to celebrate green space outside the People’s Center along with offering art as an option in their health practice.”

sPARKit is a mobile pop-up park in a trailer, complete with brightly-colored furniture, board games, and crafts. They are able to cover a sizable footprint and create an immersive atmosphere, as well as have different zones within that atmosphere – some more active or more social, others more for quiet reflection and relaxation. But in addition to offering their typical amenities that transform green and public spaces into activated destinations, Hirschmugl also offered additional activities specifically focused on health and wellness and drawing connections between health and art.

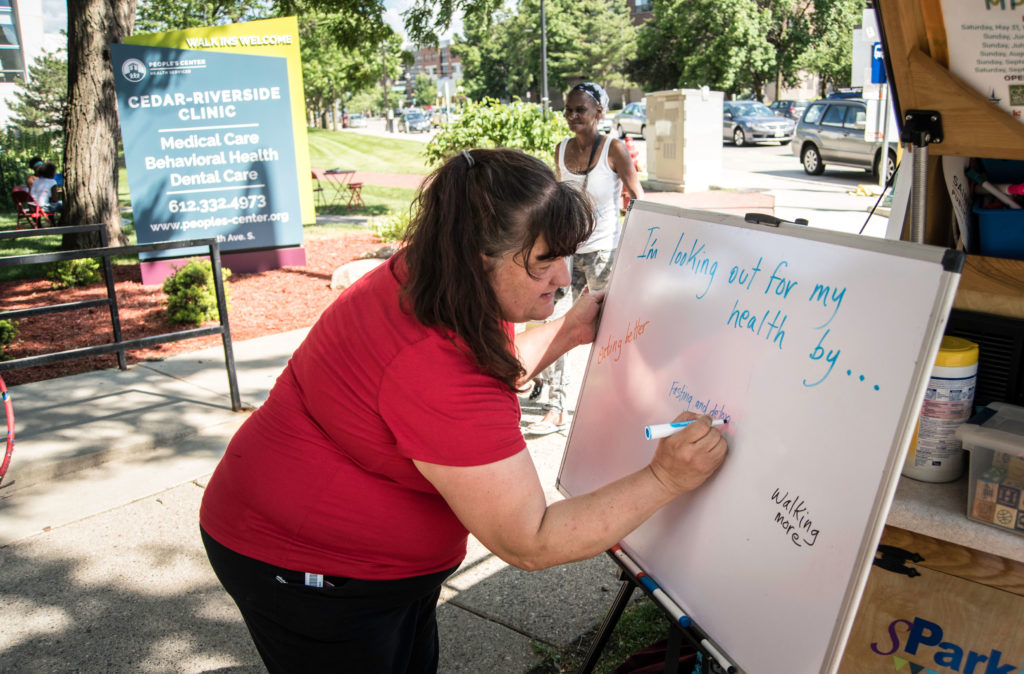

One strategy was asking a “question of the day,” getting people to write answers about what they are doing to take care of their health on dry erase boards. Hirschmugl says the got a lot of the obvious answers – drinking more water, walking more, biking more. But there were also answers they hadn’t considered: the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood where the Center is located is a very diverse neighborhood with a large population of recent Somali immigrants, and the day they were asking people this question also happened to fall during Ramadan, a Muslim religious holiday during which time observers fast from sunrise to sunset. Thus, Hirschmugl and her team also heard that people were fasting in accordance with their religious tradition, and taking time to slow down and practice mindfulness.

“The Center is located on a major bike route so there were the obvious [diet and fitness] answers, but we also got those answers we hadn’t considered,” says Hirschmugl.

In addition to the question of health practices, sPARKit also had an area set up for watercolor painting. Participants could use watercolors to paint a postcard with a message they wrote to themselves on the back following the prompt, “I’m taking care of my health by…” Hirschmugl will then mail these postcards out a month later.

“Some people were up for the prompts, and some just wanted to sit and paint,” she says. “Sometimes people just want to sit and chat with other people. We had some interesting conversations with staff members would come out and paint with us after their shifts. One staff member sat for 45 minutes to chat with people about why she likes her job.”

Hirschmugl also designed some coloring sheets that had the logo of the People’s Center in the middle surrounded by items and words, in both English and Somali, that had to do with healthcare. These were simply left in the waiting room along with colored pencils for people to color on their own. She says kids responded most to these, but she also had one older woman come out and proudly show them what they had done and asked for another sheet. Hirschmugl gave her coloring tools to take home with her, giving her the tools she needed to continue the practice in her daily life.

“You never know if people will do it or not, especially painting,” she says. She recalls a Somali woman insist that she can’t do it, she can’t paint, until she watched her friend sit down to paint a postcard and eventually sat down herself, painting a beautiful picture of a tea party.

“It took a little while for her to sit and get into that place. [Something like this] is a unique opportunity because there have been a lot of [studies] lately about how art helps people. It’s like a mindfulness practice: you don’t need to be the best at it, but just the practice of it helps. When you’re in a calm space around others where you don’t have to talk you’re unleashing something.”

Activities like the watercolor painting allow people to linger longer and have more meaningful conversations. Playing games also encourages people to hang out for more extended periods of time. During one of sPARKit’s visits, they invited a couple of local teens to play music on the lawn, and some people chose to stop by just to sit and listen to the music. All of these activities, whether it was active participation and interaction with the painting or quietly sitting listening to music, all served the larger goal of getting people to engage with this space, both as a green space and as a public healthcare center.

“We’re offering an alternative to how people see the space and also how people see healthcare centers,” says Hirschmugl. “At a healthcare center, people are naturally waiting for something they wish they weren’t waiting for. With this they had something to think about aside from worrying about being sick. They had something else that was healthy and fun. It was interesting to be in a space thinking about what people’s health needs are and offering some comfort and respite as a solution.”

Every day sPARKit was at the People’s Center, Hirschmugl would sit with Michael Johnson, a Master’s student at St. Mary’s University of Minnesota who has been observing and evaluating the Ready Go project all summer, and together they would paint postcards and chat with whoever sat down. By sPARKit’s third visit, people were accustomed to them being there and would come out and sit longer. More people would also stop by, generating more activity.

“Having it on the same day creates a level of consistency, instead of just being a one-off,” Johnson says. “Just having [the Ready Go projects present] on same day has been good decision.”

His primary role is observation, and he has been interviewing people and experiencing these projects looking for ripple effects. “I have attended all but one, largely experiencing it as spectator, gathering casual interviews as people engage with a prompt or project on their experience and involvement with the People’s Center.”

He has seen a lot of staff get involved, and they tell him that it’s a nice break in their workday and also allows them to have a relationship with their patients in a different context.

“Making art side by side creates a different opportunity for them to connect and talk about their health,” he says.

Elena Montanye, an AmeriCorps VISTA who is new to the People’s Center and now works with the Ready Go series, echoes Johnson’s observations. “As I can tell the staff really loves it,” she says. “There’s always a lot of staff outside getting involved, and for the patients it’s fun to interact with the staff on a non-medical level.”

Johnson says that while most of the participants have been patients and staff of the clinic, some people are drawn in simply because they were just walking by and happened upon whatever project was happening outside of the Center. He also calls Hirschmugl “an expert” at drawing people in and getting them to linger longer.

“Soozin was very effective in being able to go to the sidewalk and draw people in by offering a variety of things to do rather than just one activity,” he reflects. “[She had] a whole playground setup that creates a different sense of environment and a play space that makes you intrigued. Even from across the street you’re drawn to it. She was really thoughtful and learned as she went along, getting better each time. She brought along musicians the last time because sound fills the space and attracts more people in, and that got more people to stop and sit down. It’s a passive way of being involved and a few people mentioned how much that meant to them.”

He reports that the more active projects like sPARKit would attract about 20-30 people at a time, and different activities would bring in a different demographic. The Temporary Table Tennis Trailer attracted more athletic participants, while the live music played during sPARKit attracted more passive observers, and the watercolor painting created more of an opportunity to engage in depth. In each instance, he says, “People are still taking part in a social activity and there is still a value in all of those. They offer people some respite. These are small but impactful experiences.”

These activities create connections between people and are able to bridge cultural gaps, effectively communicating with people even when they don’t share a language.

“[The Ready Go projects are] meant to promote interaction and to build a sense of connectedness, especially in this community,” says Johnson. “Being able to provide something that provides a sense of joy and a break in their day, with the conversations we’ve had and the smiles we’ve shared we know we’ve made a difference. It’s more than just fun and games.”

Both Hirschmugl and Johnson recall a Native American woman who sat for an hour, making sketches and then painting a picture of a dream catcher. Her partner commented to Hirschmugl afterwards, “This is really nice because you guys are so inviting, and not a lot of people invite you to sit and talk to them.”

“She seemed like she was having some anxiety when she got here, but as she sat there painting she just seemed to calm down and was in a little bit better of a place when she was done,” Hirschmugl remarks.

“We want to give people the opportunity to connect with the experience through the artwork, then connect it to their healthcare experience,” she says. “What makes ‘public health’? Having opportunities to create or make without being judged is important, and then people will keep doing it as a practice, just like exercising and drinking water.”

[…] event featured Ready Go mobile artist Soozin Hirschmugl, who brought games and coloring projects. Though they were all very different events, Mouacheupao […]

[…] the pop-up’s impact. While more than 500 people participated, and an evaluator reported that as many as 30 people would cluster at a popular station at any given time, Noor said it’s not possible to gauge […]