Queer and Undocumented: The Art and Activism of Coming Out, and Coming Out

June is Immigrant Heritage Month as well as Refugee Awareness Month. In solidarity and support, we will run a series of artist profiles and features this month about the experiences of undocumented artists, from a first-of-its-kind fellowship for undocumented artists to LGBTQ artists whose experiences coming out as queer gave them the language to then also “come out” as undocumented. Read the rest of this series here.

“I always like to say that I’m an artist who is queer and who happens to be an undocumented immigrant,” said Brian Herrera, a graphic artist based in Chicago. “I would like to meet more undocumented queer artists because I feel like, according to society, that’s the worst thing you can be.”

According to a report published by the Center for American Progress in 2013, there are at least 267,000 adult undocumented immigrants living in the United States today. These queer undocumented Americans face increased risk of hate violence, especially when held in detention. And while they experience discrimination and trauma here in the U.S., some are fleeing persecution in their home countries and seeking asylum here.

Additionally, many queer undocumented Americans are also people of color, making them triple minorities in a society that too often and too readily discriminates against any one such status.

But being queer and undocumented does not make a person a helpless victim. Queer undocumented youth built the immigrant rights movement, starting in 2001 when Tania Unzueta was scheduled to testify on Capitol Hill for the federal DREAM Act, introduced in August of that year, about her experience growing up queer and undocumented. That hearing never happened because of the 9/11 attacks. Unzueta went on to found Chicago’s Immigrant Youth Justice League and work as an organizer with the National Day Laborer Organizing Network.

Since the massive immigration reform protests of 2006, the immigration reform movement has continued to grow and gain momentum, and DREAMer activists had captured the spotlight, remaining at the forefront of the national immigration conversation until the current administration’s “border wall” anthem was punctuated by a parade of human rights abuses and the bodies of dead migrant children. DREAMers took inspiration from decades of LGBTQ advocacy, making “coming out” about their undocumented status an important part of their activism, arguing that visibility plays a crucial role in changing widespread discrimination and, eventually, acceptance.

“A lot of immigration movements that led to people coming out about their status were led by young, queer, undocumented activists who took that language from the queer liberation movement,” said poet Marcelo Hernandez Castillo. “Even in this very masculine, misogynist, patriarchal Latinx community, they got that language from queer movement.”

In 2007, queer undocumented youth galvanized to form their own advocacy organization, DreamActivist, recruiting a coalition of progressives, including queer undocumented youth, to push forward the DREAM Act as standalone legislation separate from comprehensive immigration reform.

“From our lived LGBT experiences, we knew that the way to formal equality for undocumented immigrants was to use our stories as our weapon, to ‘come out’ as undocumented, just as we had come out as gay, lesbian, or transgender,” writes Prerna Lal, civil rights activist and attorney and co-founder of DreamActivist, with co-author Unzueta.

The activism of queer undocumented youth, organizing at the intersection of LGBTQ and immigrant rights, has continued to grow and strengthen. And queer undocumented artists have played a significant role.

Illustrator Julio Salgado, who was born in Ensenada, Mexico and grew up in Long Beach, California, launched the UndocuQueer movement in 2013, a billboard project he created in collaboration with queer undocumented activists throughout the country.

In an interview with The Huffington Post, Salgado said, “There’s homophobia within our communities so what we need to do, the undocumented people who are also queer, [is] call out and say, ‘Hey if you’re talking about social justice and you’re trying to talk about treating everybody equally, we need to start with ourselves. How is our homophobia affecting certain things.’ And likewise when you’re in queer spaces, a lot of the times [what’s said is] we should focus on gay marriage, we should focus on joining the military, but we don’t focus on immigration.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Emmy-nominated filmmaker, and Tony-nominated producer Jose Antonio Vargas has produced films and written a book about growing up queer and undocumented in America and continues to be actively involved in immigrant rights advocacy. He serves on the advisory board of TheDream.US, a scholarship fund for undocumented immigrant students, because he is passionate about the role of arts in society and promoting equity in education.

Vargas founded Define American, a nonprofit media and culture organization that works to humanize the conversation around immigration and fight anti-immigrant rhetoric. The organization was founded the day Vargas officially came out as undocumented in an essay for New York Times Magazine. Define American continues his work promoting the arts as a tool to connect people, transcend politics, and shift the national conversation around immigration, and just this year they launched a first-of-its-kind fellowship for undocumented artists.

The immigration rights movement of the last two decades is inextricably tied to and informed by the LGBTQ rights movements, and queer undocumented artists have been on the front lines. Following are the stories of three young, queer, undocumented artists and activists who spoke to Creative Exchange about growing up queer and undocumented in America and shared their experiences of coming out, and coming out.

Art and activism

Brian Herrera was born in Veracruz, Mexico but has been living in Chicago since 2008. He was eight years old when his mother brought him to the United States—a year too late for him to be eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which only applies to persons brought into the United States as children prior to June 2007.

He doesn’t let that get him down, though. Now 22 years old, Herrera was always raised to be proud of who he is, even when it posed a challenge.

“My mom is also undocumented and she was always super proud of who she is,” he says. He knew since he was first brought to America that he was undocumented, and there were times that it brought on some difficulties. For example, he wanted to go to college but it was difficult for him to find scholarships or other forms of aid that would allow him to. But, he says, it never brought him down.

“I don’t like to center the narrative on it being a hardship because I feel that even though it’s a major challenge, I’m still able to pull through,” he says. “I’m 22 years old. I work for myself. I’m doing what I love. I feel like being undocumented was just another challenge in my equation, but I kind of embrace it. I love the fact that I’m undocumented; it sets me apart.”

Herrera only just came out as undocumented last year, even though he has known since 2008. He says he had just turned 21 and felt that he “needed to do something with my life.” For the past several years he has been working with the Organization of Communities Against Deportations based on the south side of Chicago, an organization that works on preventative tactics and resources for undocumented folks.

He’s also done activism work within the city with organizations like the National Museum of Mexican Art, Puerto Rican Arts Alliance, Illinois Humanities Council, and the Free Street Chicago Theater and Performance for Social Justice.

It was through this activism that he actually “got serious” about his art, and he has done a lot of work around gentrification awareness and housing rights.

“I grew up on the west side of Chicago and my neighborhood was going through gentrification,” he recalls. “I definitely noticed the changes and I wanted to act on it, so I was doing a lot of activism work like community organizing and volunteering. But I wanted to do something that directly involved in my art.”

He started creating artwork for gentrification campaigns using guerilla marketing tactics like wheat pasting.

“That was my first exposure to the hyper local art scene, and it also motivated me to do more work that speaks to my community. I’ve been defining what that means ever since.”

When he moved to a Pilsen, a Latinx community with “cheap rent,” the irony of moving to a neighborhood for the same reasons his previous neighborhood had been experiencing the gentrification he had been fighting against was not lost on him.

“I wanted to put in the work and contribute to my community,” he said. “Pilsen is where I learned a lot from the activist community. I organized a march for housing rights and had my first show there.”

Herrera chose to come out as undocumented because he felt that it is important for undocumented Americans to be vocal about who they are that sets them apart.

“It also dissolves the fear, the xenophobia aura around it,” he says. “I think it’s something that’s very normal and something that should be more normalized, especially in the Midwest.”

He has found that when he is very public about his undocumented status, people are always curious and want to know more, but they also treat it as something tragic, so he tries to bring a positive light to it.

At about the same time Herrera came out as undocumented, he also came out as queer. He says that coming out as undocumented helped him to be able to shape more about his external self and be more unafraid and unapologetic about who he is.

“Being undocumented was just a fact. It was a status that I had that I couldn’t do anything about,” he said. “But accepting who I am to come out as queer was something that I had repressed my entire life. The first part of coming out as queer was really accepting that it is who I am.”

Now Herrera tries to exclusively focus his work on queer communities of color. Currently he is part of the first ever cohort of undocumented artist fellows with Define American. He says that being part of this fellowship has further helped him to take his work a step further and look for more queer artists of color in the Midwest and on the East Coast.

Poetry and pride

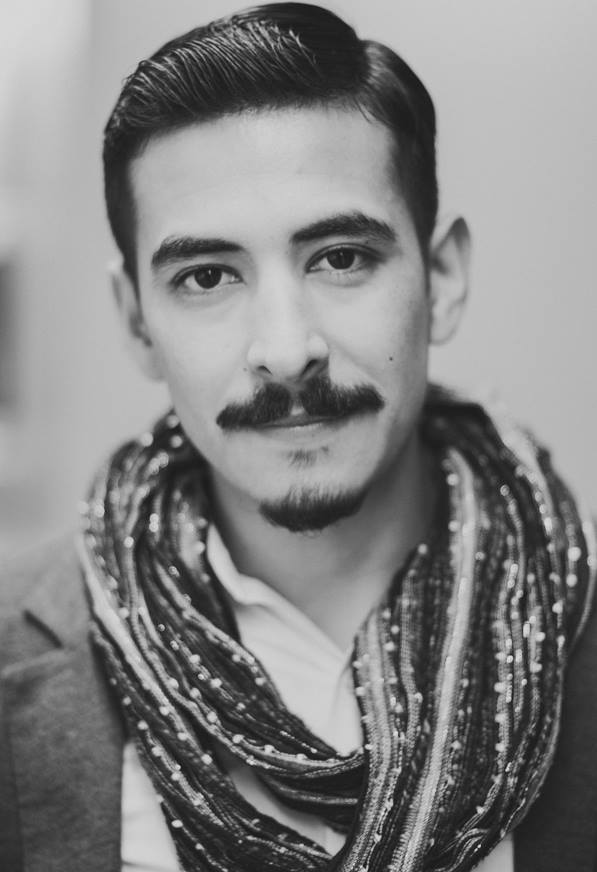

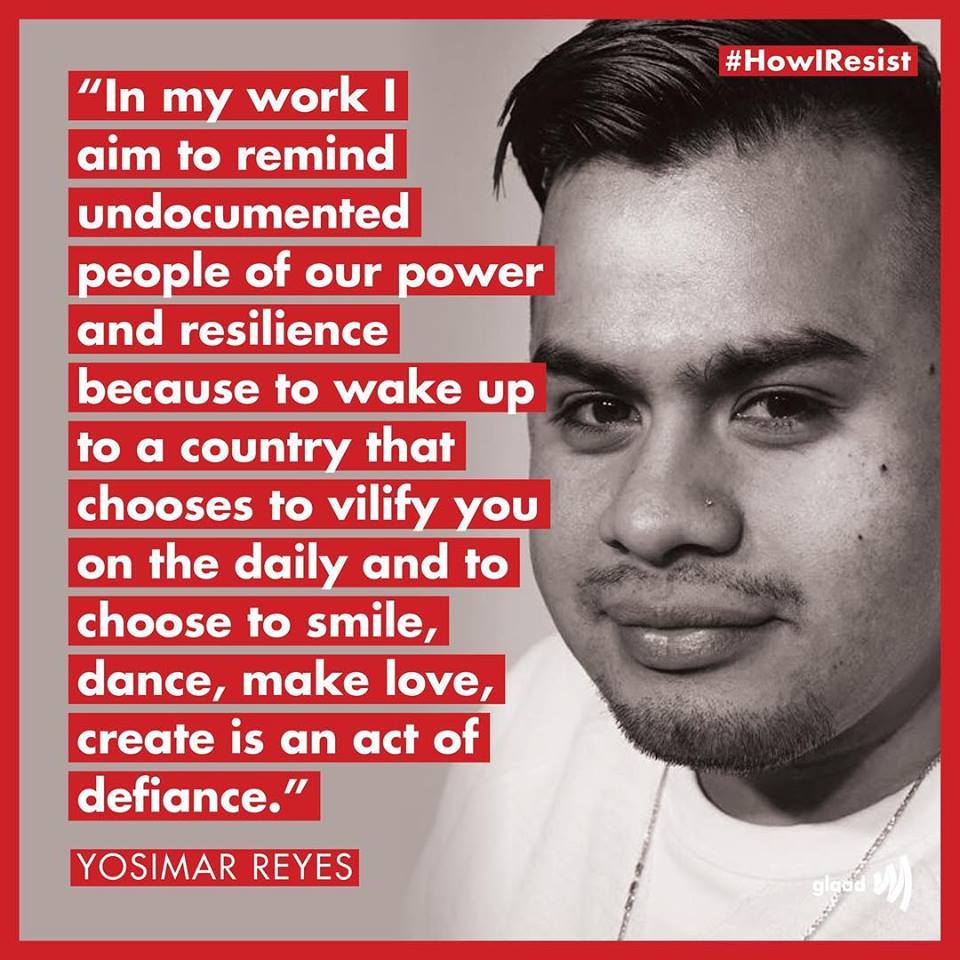

“It goes without saying that coming out of the shadows with this movement was inspired by LGBTQ activism, but I knew I was undocumented at a very young age and all of my friends were too, so it wasn’t a big deal. It wasn’t really a phenomenon,” says poet Yosimar Reyes. “Coming out to myself [as queer] was the hardest thing, being queer and knowing that my life is going to be one of constant education of other people.”

Reyes was born in Guerrero, Mexico and is a DACA recipient. He travels the country as a nationally acclaimed poet and public speaker, and has been named one of Advocate‘s “13 LGBT Latinos Changing the World.”

“I think what’s awesome with the activism of undocumented folks is that more people are talking about it and making it less taboo,” he says. “My friends are all out as undocumented and don’t feel any fear about it. I think it’s important to show that—it explains to our community that we can be more than our status.”

Reyes is passionate about “building undocumented power in a way that’s transcendent.” He emphasizes that undocumented people have agency; they are not just victims of the system. Undocumented people have their own power.

“We’ve made undocumented people these kind of victims, but I want to show how powerful we are and how we’ve developed our own systems of survival,” says Reyes. “We’re still surviving. We’re still opening businesses. We’re not self deporting. I’m shifting the narrative and bringing a fresh perspective; that’s how my work ends up in different places. People aren’t used to undocumented people talking back, but I’m very much about that.”

He also doesn’t mince words or tiptoe around his thoughts. “If you don’t accept us because we don’t have a social security number, that’s a journey you need to go on because I can’t help you with that.”

Reyes was brought to the United States when he was three years old. His family settled in San Jose, California, in the city’s predominantly Mexican east side. He says that everyone he grew up with was undocumented, so he grew up with a sense that is was normal.

In high school he discovered poetry and saw Latinos performing spoken word and speaking “Spanglish.” He began signing up for poetry competitions and performing all over the city at different schools. At age 19, he published his first book of poetry, Speak Softly.

“I was talking about being undocumented long before it was a thing,” he says. “I was told not to or I wouldn’t get hired, but I didn’t care, and I think that’s what got me noticed.”

He says there aren’t a lot of Latinos or undocumented people or queer people doing spoken word, and he believes being all three helped him to stand out. But, he is quick to remind anyone who might conflate the two: ‘undocumented’ is not an identity the way queerness is.

“It’s more like a social condition, like poverty. It’s something I grew up in and something that surrounds me in my world,” he says. “My queerness is something very integral to who I am; it’s a part of my being, as opposed to being undocumented.”

Bridging his queerness and his undocumented status has informed his writing and made him want to create a body of work showing pride and power. “In order for me to keep living I have to remind myself and others like me that we keep going and that’s our resilience.”

Reyes has been doing this work for a decade now, and it is his full-time job. He develops work with undocumented audiences in mind, first because too often the conversation about undocumented people is not actually led by undocumented people, but also because too often the work produced by undocumented people is to educate people about their lives.

“There’s this constant need to position ourselves in this vulnerable place just so people can feel empathy for us, and I just got sick of doing that,” he says.

Right now, Reyes is working on a one-man show called Prieto about growing up as a queer undocumented child in San Jose. It’s a comedy.

“I wanted to approach this from a comedic standpoint and use comedy to shift people’s perspectives of undocumented people,” he explains. “It’s hard for people to believe that there are undocumented people who feel joy.”

Fear and love

Poet Marcelo Hernandez Castillo had a different experience growing up undocumented. It was not one of pride or quiet acceptance. It was one of fear.

Castillo has seen his father deported and later kidnapped and his mother self-deported. Both parents are now seeking asylum in the United States.

Born in Zacatecas, Mexico, he grew up in the Central Valley of California, became a DACA recipient in 2014, and was the first undocumented student to earn an MFA at the University of Michigan. While studying at Michigan he also co-founded the Undocupoets advocacy campaign to protest the citizenship eligibility requirements of many first book publishing poetry contests in 2015.

“I knew I couldn’t submit to first book poetry prizes [because they typically required] a social security number or U.S. residency,” he says, explaining that a lot of these places didn’t realize that was even part of their eligibility requirements simply because those requirements dated back to the 1920s and have been there ever since. “So here I was trying to write a book knowing that, realistically speaking, one of the most viable ways to get a book of poems published is through the contest circuit—agents aren’t really for poets; you just do it on your own. So I was writing a book knowing I might not be able to even get it read.”

Through the advocacy of Undocupoets, Castillo and his fellow activists have been able to get the eligibility requirements changed for 10 highly visible and renowned first-book poetry contests, establish a fellowship for undocumented poets, and are building capacity to support residencies for undocumented poets.

They are focusing on residencies now because of the structural barriers that still exist around them for undocumented writers. Even when citizenship requirements are changed, accessibility is still an issue—the travel required to attend residencies can be cost-prohibitive—yet residencies are also where a lot of access is “granted” and community-building happens. In short, being cut off from one opportunity can effectively mean being cut off from many others.

Undocupoets is also building out a website with archival capabilities so that there is a backlog of work by undocumented writers that people can access (essentially a digital library).

While he has always been aware of his undocumented status, Castillo kept it a secret for a long time. And even though he did not explicitly write about his experiences growing up undocumented, those experiences still informed his work.

“It was mapping an interiority,” he says of his earlier work. “It was mapping the emotional resonances that are left behind after the news vans has left. It was documenting for myself a place for myself because I have these behaviors and fear instilled into me, and those translated into my poetry.”

His first published book, Cenzóntle, used surrealism and deep imagery to express what he needed to say because he couldn’t find another way to say it. He says his next book, a collection of essays that serve as a memoir called Children of the Land (to be released by Harper Collins in 2020), is much more direct.

“I found it easier in prose to step away from the metaphorical and instead started to become a lot more frank and direct in my prose,” he says. “It forced me to come to terms with saying things directly. I couldn’t afford for people to misunderstand the work in the way some may have in the more cryptic manner of my poetry book. That’s my overall feeling right now: we need to be more direct. I couldn’t allow myself to operate the way I did in my poetry book, especially with this administration.”

He admits that he is scared for his book of essays to come out, especially since he is actively applying for citizenship and is afraid that something he wrote might become grounds for denial of his application. Still, he felt it was important not to censor himself while he was writing. “I had to really negotiate how much can I say how and how much I want to say,” he says.

Receiving DACA in 2014 gave him some sense of feeling “protected” that ultimately emboldened him to write these essays, and also made him feel as though he had “permission” to finish Cenzóntle. DACA was also the reason he finally “came out” as undocumented to his friends and started his advocacy work with Undocupoets.

But he didn’t just come out as undocumented in Cenzóntle; this collection was also his way of coming out as queer to his wife.

“The book is about coming to terms with being queer in a heteronormative institution, and a monogamous one at that,” he says. “I think coming out first to my wife as queer gave me the language to come out to other people as undocumented. It gave me the right state of mind to position myself as a person that has kept something from other people and then suddenly revealing it. The parallels all meshed together.”

He further compares his queerness to this undocumented status in the ways in which people view them both as a dichotomy: the “official” boundaries that exist between someone who has papers and someone who doesn’t are not dissimilar to the way people view sexuality as an either/or. But in terms of his sexuality, he saw himself existing less within those boundaries and more on a spectrum. Coming out to his wife was his first challenge; that then gave him the courage to come out to his friends as undocumented.

“It was scary because right now there is this culture of ‘undocumented and unafraid,’ and people are out with their statuses to remove the shame from it because it’s nothing that you did, but in my high school and college experience it was still part of the culture to hide,” he says.

He has always felt the shadow cast over his life by his status, and that shadow has always been present in his work.

“I felt like I have always been writing about my status and that it has always been my subject, no matter what I was writing about—whether I was talking about desire or sexuality, it was all within the framework of my precarious immigration status.”

Lead image: UndocuQueer illustration by Julio Salgado.

This is a great article. Very informative. I know I am later, but Thank you so much for writing this piece.