Leslie Barlow is working to build community, capacity, and equity in the arts world, 9 artists at a time

Leslie Barlow says she’s always been interested in art from a young age, then laughs as she adds, “A lot of creative people probably say that, but it’s true.”

The Minneapolis artist says she was a creative kid with parents who nurtured that side of her, but it never occurred to her to pursue it as a professional practice until later in life. She laughs again: “That’s also probably true for a lot of artists.”

Nowadays, as an artist, arts educator, and arts organizer, Barlow has dedicated herself to nurturing the creativity in others and helping them to see the potential of a career in the arts for themselves. But, as a woman of color, coming to that realization herself didn’t come quickly or easily, even as she attended art school.

“In these spaces where you are exploring art and talking about art, you’re usually shown art from artists who have long been dead,” she says. “There are a lot of Western historical influences. So I didn’t really have any concept of what a contemporary artist looked like, and I did not see myself in that kind of space or role.”

When she initially went to college, she thought majoring in design would be a good option—a major with a direct career path that was still an applicable way for her to use her art and also make money.

“I felt like that was the smart option, but once I got to college I realized what was always in me was this drive to create, and not for clients,” she remembers. “It was this innate interest in expressing myself through art that was reestablished in me through those foundational courses.”

She rediscovered her passion for artmaking at University of Wisconsin-Stout. In art she found a space where she didn’t have to be anything other than herself.

“As a Black woman in rural Wisconsin, and as a mixed race woman in Minneapolis, there weren’t a lot of spaces where I felt I could be 100 percent authentically myself,” she says. “I felt like I had to play up or play down aspects of myself to fit in. Art was the one place I felt I could be authentic to myself.” She pauses, then adds, “I did have a natural ability too, which was helpful!”

She earned a BFA in studio art with a focus on painting, then moved back to Minneapolis after graduating. She knew she wanted to somehow be involved in the community, creating community spaces and spaces for dialogue for artists.

“I always had an interest in art and community,” she says. Growing up with both of her parents working as public school teachers and both being very active in their community through the church, with youth, and in the politics of education, she says she never saw herself or her work as being separate from politics or from things happening in the community. These things were just intrinsically related.

Barlow initially thought working in galleries was the answer, but it wasn’t quite what she was hoping for.

“The spaces weren’t as diverse as I was hoping,” she says. “It felt like you needed to speak some type of language or have access to these types of spaces. As I developed my own practice and was figuring out what I wanted to do, I knew I wanted to try to change what I had been experiencing in art spaces as a woman of color.”

After a few years balancing a full-time job with her art practice, Barlow made the choice to go to graduate school. She attended the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where she earned an MFA in Visual Studies.

“Balancing a full-time job and being a full-time artist is not realistic,” she says. “Trying to pay for rent and art materials—it’s extremely difficult to do, but you need a full-time job to pay your bills. I figured grad school would be the best option to kind of pause, focus on my art practice, and be really full-time in that without other distractions.”

She says she learned a lot about the direction of her own visual work and established more of a voice in her work, expressing the things she wanted to say.

“I started coupling the subject matter in my visual work with actions I was taking in the community, and by the time I left grad school in 2016 those things were very aligned.”

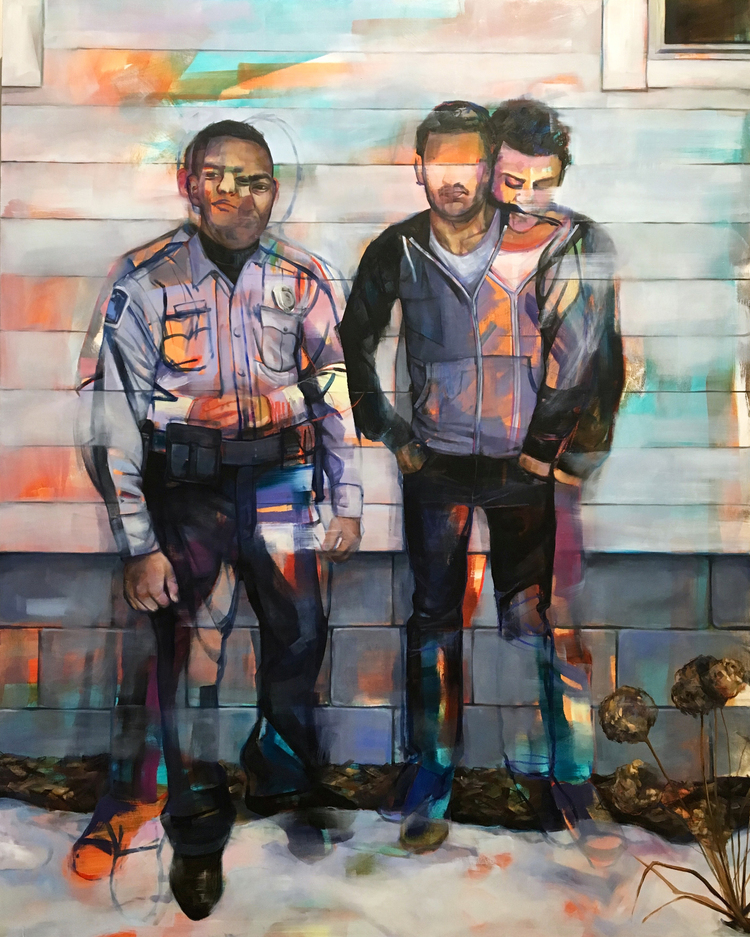

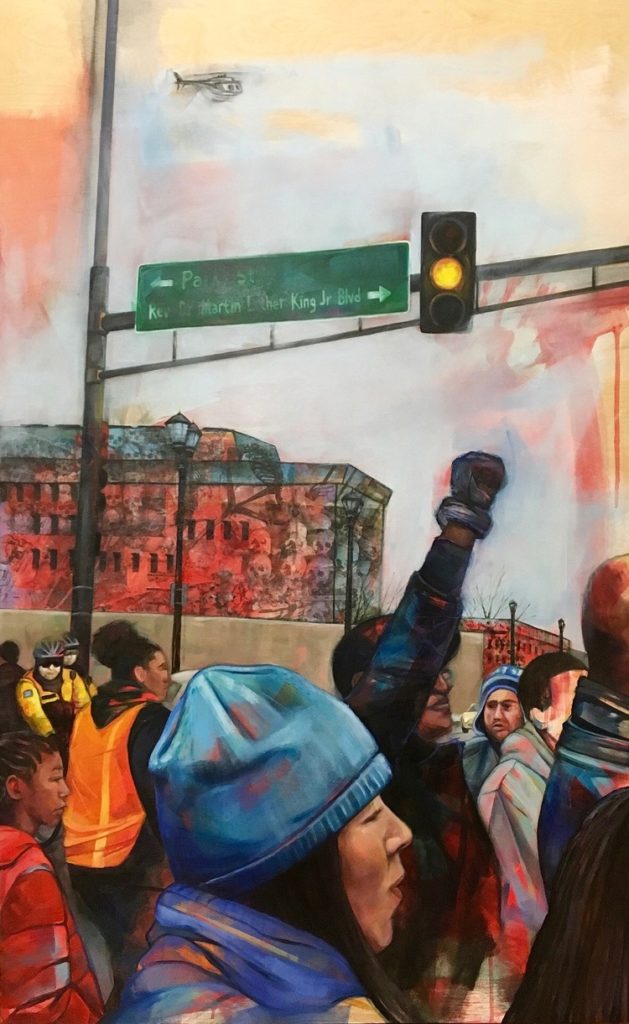

Her work as a painter is figurative and large-scale. It’s roughly a 1:1 ratio, so an observer can look directly into the eyes of the person in the painting. She mixes oil painting with collage elements, incorporating everything from photo transfers to drawings to quilting techniques.

“I layer materials to speak to the complexity of identity and how it informs our relationships and how we move through the world, particularly about racial identity, mixed race identity, and racial constructs,” she explains. “My work is often centered on mixed-race-identifying people or interracial family dynamics or people in interracial relationships. I think a lot about intergenerational racial trauma. I think about resiliency. I think about gender dynamics in relationships.”

The politics of representation is a particular area of focus. Through her work, she examines whose identities and stories and relationships have traditionally been excluded from the entire history of oil painting, which is rooted in Western traditions. She takes these historically underrepresented or marginalized stories and includes them in her painting. Painting as an art form and as a cultural practice has a wealth of history dating back centuries; millennia even. We’re taught some of this history as kids—most people are at least familiar with the names Picasso and van Gogh and so many of the other famous white men. But does that mean there were no women painters, or no painters of color? Obviously (one hopes) not, but women artists and artists of color were simply not considered “important,” and even at a time when there is interest in those “missing” artists and their stories, so many of their stories and works have been lost to time.

Barlow is keenly interested in elevating the work of artists of color and women to that same place of esteem, as well as works about such people. The people in her pieces are always people in her community—friends, family, people she is in contact or working with.

“I’m really interested in painting regular people, which I think is important to say because these are real people with real lives, not made from my imagination but also not celebrities either. People often know the people in my work.”

Today, Barlow is a full-time artist as well as an arts educator—something she resisted doing for a long time, having grown up in a household with two teachers and deciding it wasn’t for her. But by the time she finished grad school, she realized she hadn’t had any art teachers of color, and her position on teaching changed.

“There were very few educators that I could talk to about my work where they had a level of understanding and I didn’t have to educate them on my identity,” she says. “Half of my conversations [when presenting my work] would be me having to justify my experience.”

She started thinking maybe that’s part of the reason, in addition to the financial barriers to expensive art schools, that maybe there aren’t as many people of color in art programs—because they don’t feel seen by their teachers.

“I started to see that I could affect some real change in the classroom by being in those spaces,” she says.

She said teaching at Juxtaposition Arts, a nonprofit youth art and design center in North Minneapolis, “sealed the deal” for her. She loved seeing these young people, ages 12-21, getting excited about art, and loved seeing the trajectory of their work even after a short period of just a few months.

“To see these young people supported in a community of artists that look like them and that reflect their interests in a space that felt safe, sacred, and inspiring, I felt that if this can happen at Juxtaposition, we can bring that into other spaces,” she says. “Art classes don’t have to feel oppressive or scary, like me feeling like I couldn’t speak my truth for fear of people misunderstanding it.”

Barlow now teaches art classes at a number of different schools in the Twin Cities area, ranging from private colleges to public universities, and she values how the types of schools have introduced her to different types of people.

“I like to see how different people learn, what they’re interested in, and how art plays into their lives,” she says. “That has informed my practice as well—to see how important art is to people, whether as a place to escape by making work, a respite from other things in life, working things out, or trying to say something powerful, it really weaves into every community.”

These days, Barlow is doing the kind of work she had envisioned for herself since her days fresh out of undergrad: She is creating community spaces for artists. As the founder and program director of Studio 400, an artist community and studio space in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District, Barlow is spearheading the effort to create and space for artists—particularly artists of color—to feel supported and have community.

The concept for Studio 400 came to her much as her sudden desire to start teaching did—it came out of her own frustrating experiences, realizing that other artists of color are experiencing the same things, and wanting to do something to change those things. And it all started when Barlow was looking for studio space to make her work.

“To show work you need a place to make work, but there’s a lack of affordable studio spaces in Minneapolis and I didn’t know where to look to find something that I could afford.”

She reached out to one of her graduate school mentors, Tricia Heuring—a curator, arts organizer, and co-founder of the multi-disciplinary arts platform Public Functionary. Through one of Heuring’s connections, Barlow was able to gain access to studio space inside the Northrup King Building, the largest arts complex in Minnesota. Within just a few months she realized, there are no other people of color here. Other people even pointed it out to her: During Art-A-Whirl, the largest open studio tour in the country, visitors would comment to her that she was the first Black person they had seen all day.

“That’s not okay. There are 300 studios in that building, and the only way I got in was because I knew somebody who knew somebody,” she states.

At such an in-demand building, she explains, people will bring in people that they know, in much the same way that she was able to get in because of a connection. And if most white people primarily only know other white people, then you end up with a building of 300 studios filled almost entirely with white people.

“There’s not even a way for other artists to get that access,” she says, “so understanding how that system was working and had been for decades, I reached out to the building owner and asked if there was anything we could do about it.”

Barlow spoke to then-owner Debbie Woodward and told her about the idea she had to create a space inside the building dedicate to younger artists, aged 30 and under, as well as artists who typically wouldn’t get support from mainstream and institutional systems, like people of color, women, and trans artists.

Woodward thought it was a great idea and said that she had a space coming up vacant soon. And it was then that Barlow realized…she had never run a program before.

She laughs again. “That’s when I reached back out to Tricia. She and Mike [Bishop] of Public Functionary were transitioning out of their space and wouldn’t have one for awhile, so it was a really great time to put our powers together.”

Studio 400 is now a program of Public Functionary, which is sponsored by Springboard for the Arts. It is a 2,000-square-foot space with semi-private studios for nine artists, as well as a storage area, lounge area, and community area where they have programming like monthly meetings and skill-building workshops. The studios are subsidized, so each artist pays $100 per month and Public Functionary covers the rest to make it financially feasible for these artists.

Barlow says that Studio 400 is not a residency program but a platform. It is also not a permanent space for any given artist: The nine artists currently in studio have the option to stay up to two years, after which (in 2021) another open call for artists will go out.

“The goal is for them to gain enough visibility and knowledge to move on to their own studios,” she explains. “They’ve even been practicing paying for their studio space. So they can then move on to the next thing and a new cohort comes in, and now our community [we’ve fostered out of Studio 400] has doubled.”

The application process is simple. They wanted to eliminate all barriers to access, so there is no prerequisite that the artists have gone to school. The artist provides samples of their work and has answer just a few questions, which focus on issues like how the artist works in a collaborative environment (because the studios aren’t private) and what barriers the artist has come up against in their practice. Studio 400 also asks about education and income levels because they want to support artists who have less support.

“We’re committed to addressing those disparities,” says Barlow. “I want these artists to know that you don’t need to know the secret handshakes or have the connections to be able to make it in the art community in the Twin Cities. It doesn’t make sense to me that these institutions are still predominantly white. It’s access; it’s equity; it’s a lot things, but I’m thinking about how, through this small thing, we can be intentional with nine artists at a time.”

The initial idea for a concept like Studio 400 came as Barlow was teaching at the University of Minnesota and working with young people at Juxtaposition.

“I was kind of thrust back into the mindset of when I was an undergraduate and what kinds of things I would have loved to have had in order to be successful earlier on as an artist,” she says. “I feel like we can make things a little easier, particularly for artists who have been so underserved by the art world and receive fewer resources.”

She noticed that when artists leave school they’re basically just told to fly free; they receive some professional development tools in university art programs, but not nearly enough.

“That needs to be woven into every single class: how what they’re doing in the classroom can be applied to the real world and how to sustain themselves in the real world,” Barlow says. “I wondered, ‘Is there a way for me to catch artists right as they’re leaving in that precarious time right after undergrad, when they’re taking that first step into their professional careers? Can I catch them in that moment and give them a boost and some support to make navigating an artist’s career path a little easier?’ That’s when most people attempt to keep the art thing going, but then they need to make money and pay rent and it becomes difficult to sustain a creative practice. It seems like excess and it’s definitely a privilege to spend a majority of your time making art. So I wanted to find what I could do to remove some of the barriers to an artistic career.”

As someone who is professionally just a few years ahead of the first artist cohort at Studio 400, Barlow sees herself in those artists and in a lot of what they’re working on right now.

“Seeing these artists’ practices flourish in this space, in that community that I was craving after undergrad, and I created it—it’s incredible,” she says. “Because I’m able to share whatever knowledge that I’ve built up, they’re gaining a lot of knowledge, too. My hope is that that circle continues to grow.”

Barlow is a 2019 Springboard for the Arts 20/20 Artist Fellow, and she says that fellowship is what has made Studio 400 successful.

“It costs money to run a space like this,” she says. “It’s interesting that someone like me would take this project on, because it’s not like I had funding to take on this entire space and provide resources to these artists. I just had the drive and saw the need. I’m so thankful I got this fellowship. For me I felt like, ‘Who am I to try to do something like this?’ But at the end of the day, no one else was doing it. People saw the inequities, they saw it wasn’t diverse, but nothing changed. It just takes one person to say, ‘Alright, we’re going to change it.’ I put in the application because this was a now-or-never kind of thing.”

In addition to the support from Springboard, they also ran a GoFundMe campaign and received a Metropolitan Regional Arts Council grant for a mentorship program for the artists.

“It was a way for them to have more eyes and another voice in the room besides my own,” Barlow says. “I wanted to make sure they were getting support from multiple sources.”

She says the current cohort has had a huge impact on how the program was developed. Over the past year, they have regularly asked for feedback from the artists, and encouraged the artists to tell them how to run the program instead of them telling the artists how it should be done.

“Studio 400 can shift to being whatever it needs to be for each cohort,” she says. “You can’t fail if it’s about the people in the room.”

For Barlow, Studio 400 is a natural evolution of all of the work she has done up to this point: as an artist, as an educator, as an arts administrator, and as a member of the community. Everything she has learned and everything she is passionate all culminates in this project.

“As an artist, I know about the need for studio space. That’s the first step. As an educator, I know how young people are navigating art school and classes and what is and isn’t being taught there. As someone who regularly applies for grants and residencies, I understand all those things. I have worked in galleries and curated shows and spaces before. This was another level synthesizing all those things together.”

All photos courtesy of Leslie Barlow and Studio 400.

Applications for the 2020 20/20 Artist Fellowship for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) and Native artists of all practices, disciplines, and career stages residing or working in Minnesota are now open. Check the website for complete details.