Heidi Brandow documents definitions of “home” for Native peoples, refugees, and normalized residents

Santa Fe artist Heidi K. Brandow came by her creative practice somewhat naturally – on her mother’s side, she comes from a long line of Native Hawaiian singers, musicians, and performers; and on her father’s side, Dinè (Navajo) storytellers and medicine people. She recalls she has always been drawn to creating things and making art, but it wasn’t until 2003 when she “started to take it a little bit more seriously.”

She earned a BFA with an emphasis on painting and print-making from the Institute of American Indian Arts, and has studied industrial product design and urban planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Istanbul Technical University.

“At that point I wasn’t really convinced that my approach to art was going to be on a traditional trajectory,” Brandow says. “I was immersed in being a fine art painter, but I had a lot of curiosity still and wanted to know more about the intersection between fine arts and design. To a large extent my practice is an example of that – my painting and arts practice leaves a lot to the viewer to interpret and poses many questions. Even in the design element, I’m utilizing a simpler color palette and cleaner lines, connecting all these elements together in a painting piece.”

Brandow has worked in a variety of different formats examining that intersection of fine art painting and design, from street murals to print-making to hotel room design. One long-running series she has is mixed media project of panels featuring whimsical monsters that draw on street and pop art aesthetics.

“Looking at the monsters, a lot of that work is influenced by our day-to-day existence of living with so much pop culture, music, social media, all these trends,” she explains. “I like very bold and bright colors and I like to keep it light. The appeal of the monsters isn’t limited to a particular age group: kids like them, elderly people like them, and I take a lot of joy in that. If it has this kind of immediate and visceral affect on someone then that’s good. It doesn’t require a PhD to understand; you either like it or you don’t.”

As an artist, she says, she thinks the arts scene has moved away from the idea of being a matter of “you like it or you don’t.” Anymore it is often a matter of biennials and huge exhibitions organized around abstruse critical themes.

“It’s so heavy and complicated and dense,” says Brandow. “There’s no joy in that for me. I’m trying to find a balance. How can we connect with these really important issues but at the same time make it so that its accessible to everyone so that everyone gets it and everyone can enjoy it and participate? It’s easy to create something that’s really complicated and dense and only reaches a handful of people; [it’s harder] to take it a step further and make it more accessible to everyone. Historically I don’t come from that community where everyone went to Harvard and ten generations studied at Oxford. [Coming from Native Hawaiian and Navajo cultures], we were not a part of those conversations, and to a large part we were excluded from them. I don’t feel like I need to create work that upholds tradition I was never meant to be a part of.”

Brandow says she has always been interested in examining her cultural identity in her practice, specifically as a Native artist and questioning what that means, defining the parameters of what is and isn’t “Native art,” and examining how she fits within those parameters, if she even fits within them and if not, if that is a problem.

“I didn’t enter the art world purely by my Native identity,” she says, “but all these other labels began to attach themselves to my practice, and I’m okay with that because I understand my Native identity is a big part of who I am. In terms of how I fit into all that, I’ve just had to carve out my own niche.”

In recent years Brandow has been branching out in her work, creating and participating in projects that involve documentation and social engagement.

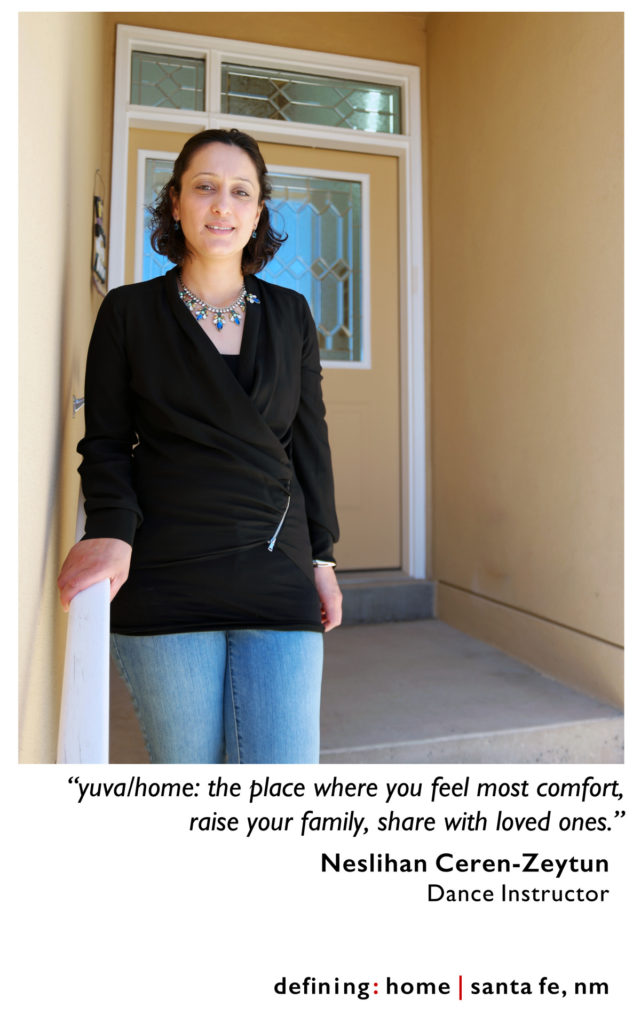

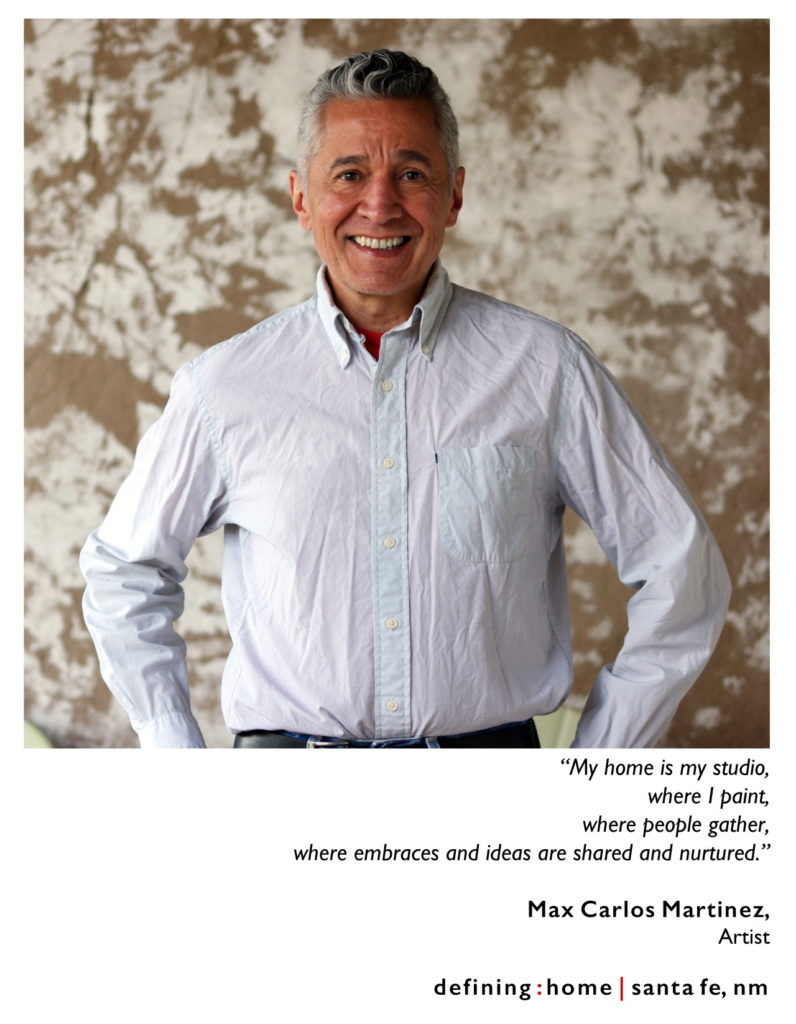

Her “defining: home project” began in 2015 in Istanbul, Turkey, with a fellowship with the Turkish Cultural Foundation. This photo and film documentation research project seeks to socially engage the public and posing the question, “What does home mean to you?” examining individual and collective definitions of “home” for Turkish residents and Syrian refugees in Turkey.

“This all came about because I had lived there several years ago and I still go back once or twice a year. I saw how the Syrian refugee crisis was really hitting neighboring countries in that region and it was really shocking. It was equally shocking coming back home and realizing no one had any idea it was happening,” she says, explaining that all of this was happening years before it became a popular talking point in American politics and human rights activism.

Upon returning home to Santa Fe in 2016, Brandow received a social engagement artist residency from the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, enabling her to continue the same documentary work with Native and non-Native Santa Fe community members, drawing connections and identifying patterns common to Syrian, Turkish, and Native American people in the context of forced migration, politics, homeland, and human rights.

“It allowed me to connect with people that I never would have had this conversation with,” she says. “It also surprised me to find that the general non-art-making audience really want an opening to participate in something artistic. l never really knew that. If you just create the opening, people want to support that. People want to be a part of it. I need to use my practice to create more of these openings and in the end have this whole other art piece that was made by the community. I was a small part in getting it going but the community made it, and I love that.”

Brandow says that more and more often her practice is built on creating more intimate projects such as that one. This fall she plans on returning to Turkey for another documentary research project with some components of social engagement, documenting people’s relationship to trash.

“In Turkey, the people involved in that industry are often refugees and those living on the fringes of society, and even though we see them every day they’re largely invisible. Who are these people? Where do they come from?”

She also connected with a co-op in Turkey that created a business that employs dozens of women, who had been unemployed their whole lives, creating textiles out of garbage.

“I’ll be documenting what the trash industry looks like and how that expands beyond our basic understanding of what it looks like,” she says.

In the meantime, Brandow is getting ready for the Santa Fe Indian Market in August, and will probably also work on some more monsters.

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

My contribution to the collaborative process is more that I feel like I’m the scribe; I’m the documentarian; I’m the listener and the builder.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I always have a question. That’s always how it starts, whether painting or social engagement, I’m always questioning something, and usually the questions are related to social, moral, or ethical dilemmas.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

My value is largely related to my community, and that experience is related to how I’m connected to my community and how that has informed who I am today – not just the community of Santa Fe but also as Native Hawaiian and Navajo. A lot of that informs who I am today and what that value measurement looks like.

(4) How do you define success?

A lot of things that make me feel like it’s a successful project is if I feel I’ve got a lot of really good feedback; that’s a good indication of success. Also if I challenged myself to pursue something that’s really uncomfortable or new territory. All the social engagement stuff is really new, so to be able to finish one of these things always feels like a big success because I feel like it was new territory and I really learned a lot.

(5) How do you fund your work?

I have a regular job in addition to my arts practice. I get money from anything I sell, and I’ve also had grant funding and fellowships. I’m open to all of that; whatever keeps everything moving and whatever I have to do to make that happen.