Counting Toe Tags: Hostile Terrain 94 documents the humanitarian crisis of migrant deaths

As the 2020 presidential election bears down on us and we find ourselves looking ahead at what is going to most assuredly be a very long, frustrating, emotionally exhausting campaign season, some of us may find the fortitude to endure by keeping in mind what this November’s presidential election is really about.

This year, more than any other year in living memory, basic human rights are on the ballot. Rights to food, water, shelter, and safety. Rights to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, to work, to an education—rights the current administration degrades, debases, and perverts at will and without consequence. Immigration, climate change, gun violence, foreign policy—ALL of these things are on the ballot this November, and every single one of them deals with human rights.

One of the most flagrant violations of human rights perpetrated by this administration is the well-documented inhumane treatment of migrant families at the U.S. border. But the humanitarian crisis of Latin American migrants fleeing their home countries in the hopes of seeking asylum, or simply a better life, in the U.S. didn’t start with Trump.

Archaeologist, anthropologist, UCLA professor, MacArthur Fellow, and author Jason De León has been studying this crisis for two decades: first through the lens of an archaeologist whose work studying ancient tools in Mexico put him in contact with several people who had had border crossing experiences, which motivated him to shift his studies to clandestine migration; then as an anthropologist interested in Latin American migration, theories of violence, materiality, death and mourning, and crime and forensic analyses.

In 2009, De León launched the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), a long-term study of clandestine border crossing in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona, northern Mexico border towns, and the southern Mexico/Guatemala border.

Over the course of his field research for the UMP, De León interviewed migrants hoping to get into the United States near the border south of Tucson. Back on the U.S. side of the border, he found various articles these migrants had left behind, including backpacks filled with clean clothes. Hundreds of them.

In 2012, De León began collaborating with photographer Richard Barnes and installation artist/curator Amanda Krugliak on an exhibition based on De León’s work on the Undocumented Migration Project. The exhibition included an installation of 1,000 backpacks and other discarded migrant possessions he had found, as well as original audio recordings from interviews he conducted with migrants during his fieldwork and video images created by Barnes taken on location at the U.S.-Mexico border. This exhibition, State of Exception/Estado de Excepción, was displayed at the University of Michigan, where De León previously taught, from 2013 to 2017, evolving over that time to reflect De León’s latest findings as well as the ongoing public debate over immigration and immigration reform, all the way through Donald Trump’s anti-immigration presidential campaign and the immediate aftermath of his election.

“I was skeptical about getting into this realm of exhibition work,” he says, “but I came around to understanding that the work we do is easily translatable to other spaces. The art exhibition reaches a much wider audience than we would through journal articles alone. I just got excited about that to expand our public outreach.”

Now, De León describes UMP as a nonprofit research-art-education-media collective, and he has a massive new exhibition in the works, Hostile Terrain 94 (HT94).

This global exhibition began as a show called Hostile Terrain that opened in Portland, Maine and Lancaster, Pennsylvania in the fall of 2018. It is a multi-media mix of found objects, video, and sculpture that has since evolved into the planned global pop-up exhibition HT94 that is being presented at more than 150 sites around the globe this year.

The name Hostile Terrain 94 refers to the year 1994, when the U.S. immigration enforcement strategy known as Prevention Through Deterrence (PTD) was implemented along the southern U.S. border. This policy was designed to discourage undocumented migrants from attempting to cross the border into the U.S. by closing off popular crossing points and forcing people to reroute through remote, depopulated, dangerous terrain through the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona. It was thought that the unforgiving natural environment—this “hostile terrain”—would act as a “deterrent” to those trying to cross the border illegally. It did not. Instead, some six million have attempted to migrate through the Sonoran Desert since the mid-’90s. At least 3,200 people have died in these attempts, mostly from dehydration and hypothermia, though that number only reflects bodies that have been recovered. The real number is likely much, much higher—easily over 10,000, De León thinks.

“The numbers we use come from the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, which only counts bodies that have been recovered,” he explains. “We have done extensive research using pigs as proxies for human bodies showing how quickly, in just a couple of weeks, the bodies are destroyed. We know from missing persons reports that thousands have gone missing while migrating. This is the human cost of this policy: thousands have died and countless have disappeared because bodies have been destroyed and never recovered.”

Prevention Through Deterrence is still the primary border enforcement strategy utilized by U.S. Border Patrol to this day.

Hostile Terrain 94 is a global participatory political art project to raise awareness of migrant death in Southern Arizona and highlight the history of this humanitarian crisis along the U.S. border that has been happening for 25 years now. De León makes it a point to note that, while horrible things have certainly been happening under Trump’s administration, horrible things were also happening under Clinton, Bush, and Obama, and no one wants to talk about it.

“With this current administration, no one is talking about migrant death,” says De León. “We’re talking about child separation, yes, but the only time you hear about migrant death is when it’s a child. Part of this work is to say that thousands of people have died and continue to die every single day. We can’t talk about comprehensive immigration reform until we look at the long history of this crisis. People don’t even realize this is happening.”

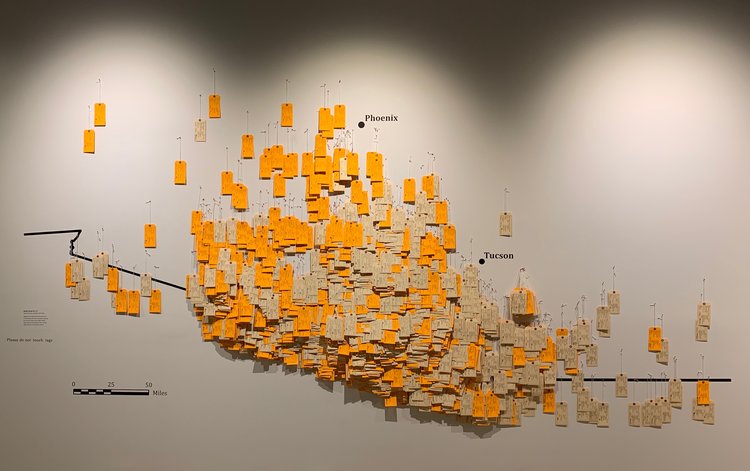

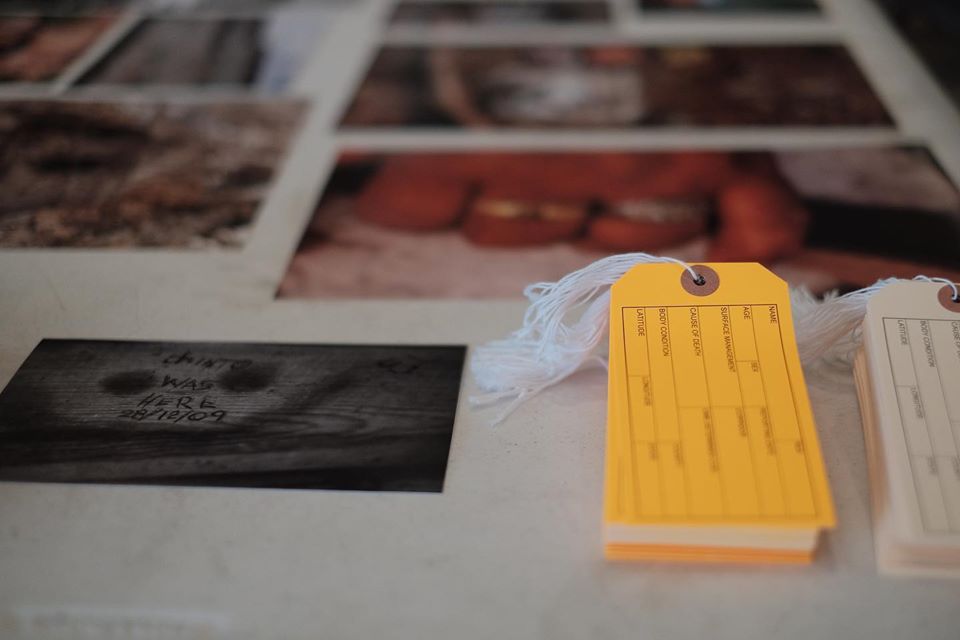

The global exhibition consists of a 15- to 20-foot-long wall map of the Arizona-Mexico border adorned with 3,400 hand-written toe tags. The tags represent the recovered bodies of people who have died crossing the U.S.-Mexico border through the Sonoran Desert since the mid-’90s; 3,400 is the estimated number of total deaths in southern Arizona by the end of 2020.

The toe tags are color-coded to indicate whether the recovered remains were identified or not, and will be placed on the map in the exact locations where each of the bodies were found. Each map comes with introductory wall text explaining the project, QR codes on some of the tags that people can scan to learn about the families of the dead and missing, and an augmented reality experience that can be accessed for free using a cell phone app that enables viewers to see the desert where the bodies were found and the harsh conditions these migrants endure. There will also be screenings of the documentary film Border South, produced by De León and Mexican immigrant filmmaker Raúl O. Paz-Pastrana.

De León’s basic idea behind HT94 was that organizations around the world interested in hosting this exhibition would receive a kit for a wall map and over 3,000 toe tags to fill out, but the rest was up to them.

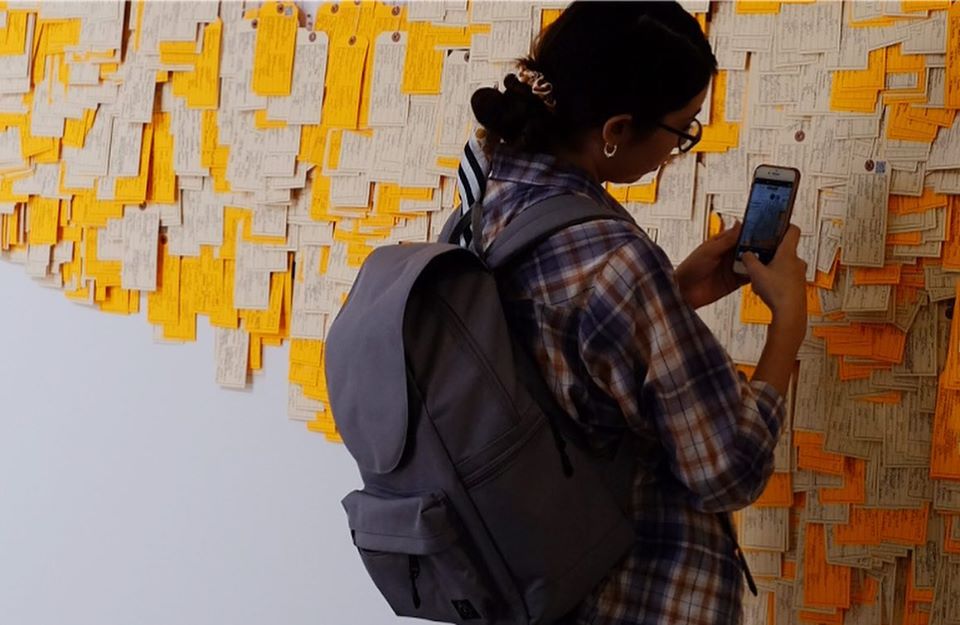

“Those places are responsible to get the community involved in filing out the toe tags and in the construction of the actual wall,” he said. “Rather than just creating an exhibit that people just go to and gawk at, we’re asking people to participate.”

The project costs organizations just $1,500 to host, and even that comparatively nominal fee has been waived under particularly urgent circumstances. It is entirely volunteer- and community-driven, appearing in community venues ranging from churches to universities. De León wanted to democratize the exhibit so it wouldn’t be expensive to host and people in the host communities could really feel connected to it by directly participating in it, playing the role of witness. His goal was to have this pop-up installation launch at a minimum of 94 sites around the world; the final tally is over 150 locations in 16 countries across five continents, including 41 states plus Washington, D.C.

“There is a lot of excitement and energy around this project, ” he said. “Especially as we come up on this election cycle and rhetoric on immigration is going to come up on both the left and the right, right now it feels like this is what I should be doing. This is the time to be really public-facing and raise public awareness on this issue.”

Several prototypes of the installation were exhibited in 2019 and will continue through this spring. The global exhibits launch this June and will run through November, with most installations occurring between August and October in anticipation of the U.S. presidential election.

For more of De León’s scholarship, read his award-winning book, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail.

All photos courtesy of Jason De León and the Undocumented Migration Project.