Rosalia Torres-Weiner brings magic kites to children impacted by deportation

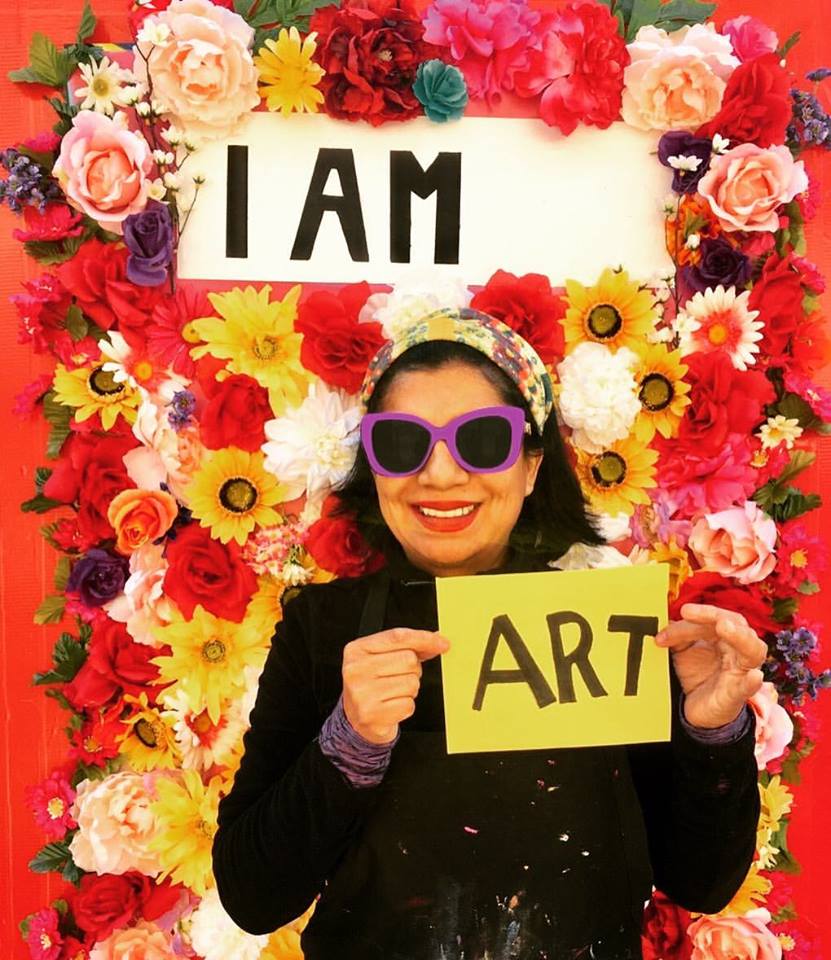

Rosalia Torres-Weiner is a multi-media artist, muralist, and activist, but she prefers to call herself an ARTivist.

Through her Charlotte, North Carolina-based Red Calaca Studio, Torres-Weiner uses art to tell the stories of the local Latino community. Her work utilizes the colors, themes, and rich symbolism of her native home of Mexico. As a self-taught artist, she had a successful business painting murals, through which she was even able to employ other artists, until the economy collapsed.

In 2010, she found herself without the steady painting work she once had. At the same time, she witnessed families in her own community being separated by deportation. It was then that she decided to pivot from commercial work to social justice work.

Her humanitarian work is based on immigration. When she first made this her focus, she remembers people telling her she wasn’t going to be successful.

“I didn’t listen,” she says. “I just kept painting and telling stories from the Latino community.”

She feels her most important work is giving a voice to children orphaned by deportations, and much of her recent work has been with the children of immigrant parents. She began by reaching out to kids whose parents had been deported.

“I knew how powerful painting is even as a kid,” she says. “I knew that it would help me feel better, even though didn’t go to art school. So I reached out to the biggest Catholic Church in Charlotte – Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church –and found kids I could work with.”

The first project Torres-Weiner did with the children was the Papalote Project, which she refers to as “the kite project,” an idea she developed to help the children affected by the deportation of one (or both) of their parents work through the emotional trauma the deportation has caused.

Torres-Weiner encouraged the children to express those emotions in the creation of kites in a fun and comfortable environment in which they felt safe. Each child created their own kite, incorporating creative skills like painting, drawing, and collage. The kites included a remnant of clothing left behind by the deported parent as a tribute to that person. The resulting art installation simulated the kites in flight, conveying a release of the emotional trauma that the children attached to the kites so the healing process could begin within a caring community.

It is estimated that for each person detained in deportation proceedings, another 3.5 people are affected – children, parents, spouses, and other family members. In 2012 alone, roughly 129,000 people were detained, affecting nearly half a million lives in the United States.

In February 2013, ten of the hand-made kites were displayed at the Levine Museum of the New South in an exhibit called El Papalote Mágico, or “The Magic Kite.” Out of this exhibit, Torres-Weiner was asked to participate in the museum’s ¡NUEVOlution! Latinos and the New South exhibit, which examined Latino culture in the South, how Latinos are changing the South, and how the South is changing Latinos.

That exhibit then led to her meeting the Director of the Smithsonian Latino Center, and now she has a mural in the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum exhibit examining the experiences of Latino migrants and immigrants making a home in the United States called Gateways/Portales, on display through January 2018. The Anacostia also acquired two of her works for their permanent collection.

The kites that began her ARTivist work have stayed with her. During a residency at the McColl Center for Art + Innovation in 2014, she developed “The Magic Kite” into a story told through 24 mixed-media panels, featuring a little boy named Tito who loses his father to deportation but finds a magic kite he then uses to fly through the sky in search of his missing father. This story was then adapted into an original production by the Children’s Theatre of Charlotte.

While at the McColl Center, Torres-Weiner thought that people in the Latino community would want to see her work on display because she was telling their stories…but, she says, no one came. Part of the problem was the issue of affordability, but another issue was also fear.

Though she has been in Charlotte for more than 23 years, she explains, “I was undocumented once. I know how it is to feel afraid to go outside and be pulled over by police. It was important to me to bring art to them.”

She had the idea to get an “art mobile” and bring art to the streets of underserved communities in Charlotte. The first thing she did when the Smithsonian paid her was purchase the Red Calaca Mobile.

“It’s very important to me that kids learn that art is a very powerful and to keep telling the stories of our community,” she says. “This way I’m connecting not just with undocumented kids but also children who are left alone in summer or when their parents are working.”

Torres-Weiner takes the Red Calaca Mobile to apartment buildings and laundromats where she sets up tables with art-making materials and invites children to come make art for free.

“I love that; I love that it’s free,” she says. “I want kids to have that opportunity to see arts like a tool, or a skill. I want them to see it differently. If they have a problem they don’t know how to solve I want them to say, ‘Let me see how I can be creative to solve this.’ They need this. We need this.”

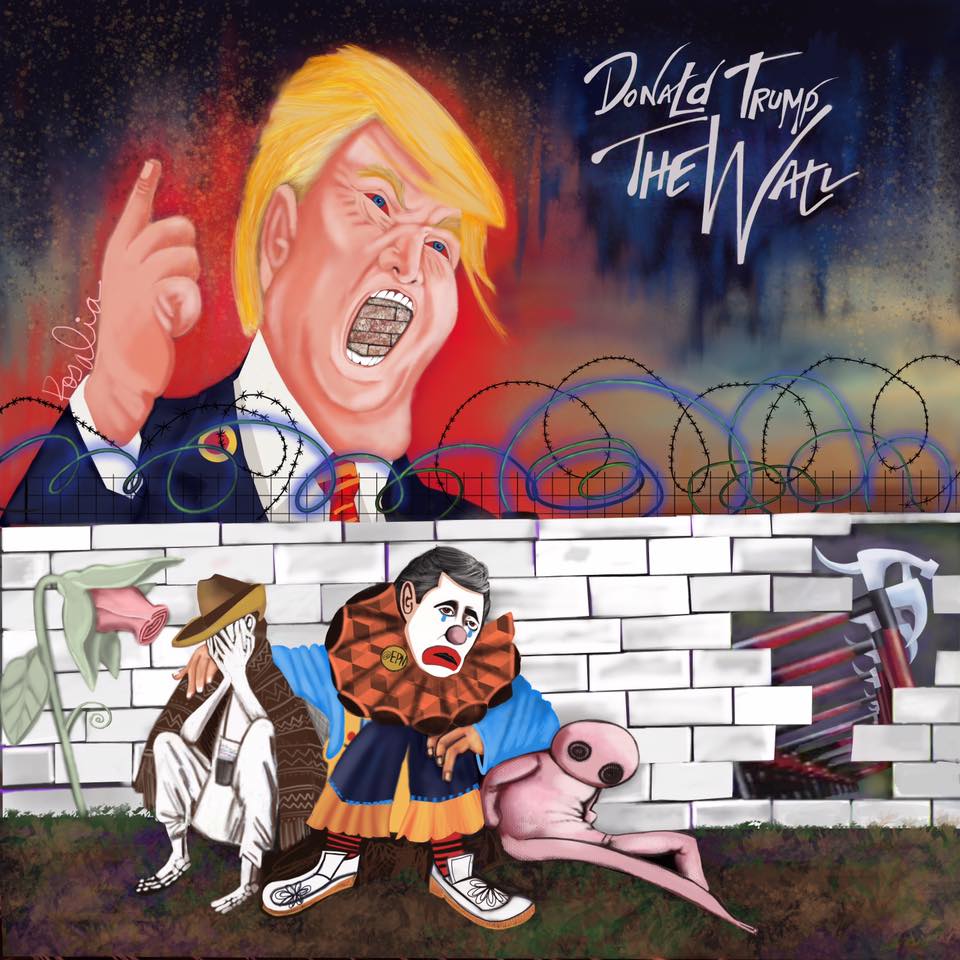

She uses the Red Calaca Studio Art Mobile to bring art to the streets and engage directly with the community. She also uses it to stage live mini-performances of “The Magic Kite,” which she stages by herself out of a vintage suitcase using “low-tech” sticks with paper figures and a 3D makeup box that allows her to show the family separated by a wall and then magically reunited.

“I try to engage people not just through colors and paintings but through storytelling and murals,” she says.

Murals continue to be a big part of her work. One outdoor mural depicts the Charlotte skyline with the Lady of Guadalupe in front, dedicated to all of the immigrants living in Charlotte. She is currently working on digital art pieces for a Dia de Muertos art installation at the Mexican Cultural Institute Embassy of Mexico in October 2017, and in September she will have another mural installed in Greensborough outside of a church where a mother has taken sanctuary with her three sons. There is a window in the room in which they are hiding where they can see a wall, so Torres-Weiner will paint a mural on that wall that they can look at every day while they’re in hiding.

“I use art to document this part of American history. This mother with her three kids is a powerful story that I need to document. They’re in hiding. It feels like we’re in the Nazi era.”

Torres-Weiner wants to be a resource for everyone in her community. If she meets a family that needs an immigration lawyer, she says she has resources for them. If other artists want to learn from her or replicate her art mobile, she wants to share with them whatever they might need. And above all else, she wants to continue telling the stories of the Latino community and bring more attention to the stories of those affected by deportation.

In October she will stage “The Magic Kite” during the Smithsonian Food History Weekend Festival at the National Museum of American History.

“I love this because this is primarily a non-Latino audience,” she says. “I love going to events where I can educate people about deportations and what is happening to families who have been separated.”

And continuing on this same food-related storytelling trajectory, Torres-Weiner will next conduct a series of interviews around Latinos in the food industry, starting with one of Charlotte’s star chefs, Joe Kindred.

“He wears a T-shirt that says, ‘If you build the wall you break the food chain,'” she explains. “I’m going to interview him about the Latino people who work behind a famous chef like him, including the people from the farms.”

Other interview subjects will include a man who worked in the Colorado mountains as a shepherd and a girl who picked strawberries.

“I wake up every day and know this is the purpose of my life,” says Torres-Wiener. “Working with kids I have found my power and I use it to wake up every day and ask, ‘What story am I going to tell today? What difference am I going to make today? Who am I going to meet who is going to inspire me today?’ One activity I like to do with the kids is lay them down on the sidewalk and draw capes around them with chalk and ask them, ‘What is your superpower?’ Everyone has a secret power they have to use to help each other.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

I love it. I always learn something new.

(2) How do you a start a project?

I contact people, I interview people, and I do a lot of research and reading before jump into doing something.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

We, the Latino community, are a big part of the economy, and I think people need to learn where we came from and what we bring to the community, especially knowing our children are the future of America. I need to empower them with their art and tell their stories because people only see one side. People need to know the other side of the stories so it’s important for me to tell our stories.

(4) How do you define success?

When I get invited to talk about my art with people who want to share my art, when the Smithsonian asks me to collaborate with them, when I get invited to do a solo exhibit at the University of Georgia, that’s when I’m like, “Yes, I’m doing a good job. I’m being successful. I just need to keep going.”

(5) How do you fund your work?

Right now it’s a self-funded project with the mobile art truck but in I’m in the process of writing grants and talking to organizations. I also got 501c3 nonprofit status so I can now go seek funds as a nonprofit, so it’s in progress.