Dread Scott is a revolutionary artist whose work takes an unflinching look at Black lives in America

In 1857, Dred Scott, an enslaved Black man, unsuccessfully sued for his freedom on the grounds that he, along with his wife and daughters, had lived in free territories for four years. In the infamous Dred Scott Decision, the Supreme Court decided 7-2 that no person of African ancestry could claim citizenship in the United States, determining that the language of the Declaration of Independence does not apply to Blacks and that the founding fathers didn’t intend for it to. The Court ruled that Blacks were “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

In 2012, Dread Scott, a revolutionary artist based in New York, staged a performance called Dread Scott: Decision. Over 75 minutes, Scott read the text from the Supreme Court decision while four nude Black men stood in front of the audience, harassed by barking, snarling German Shepherds and their handlers. Audience members participated in the piece by entering a voting booth – and being forced to walk past the men and dogs in the process – to answer moral questions like, “Would you have voted in a segregated election?” and “Would you vote in the upcoming U.S. presidential election if your vote implied acceptance of continuing the legacy of slavery within U.S. society?”

“The Dred Scott Decision is the most well-articulated argument for white supremacy I’ve ever read,” Scott says. “This is a country founded on slavery and genocide. It was the foundation of America. There is no America without slavery. We also don’t have America without mass incarceration. We don’t have police brutalizing people of color disproportionately without those roots.”

Despite a certain level of progressive-leaning self-selection that occurs with Scott’s audiences, the performance made people deeply uncomfortable.

“It was the longest 75 minutes anyone has spent in their lives,” he says. “It was a disturbing piece. A lot of it was designed to be uncomfortable in several ways. It was really a piece about United States democracy and its relationship to Black people.”

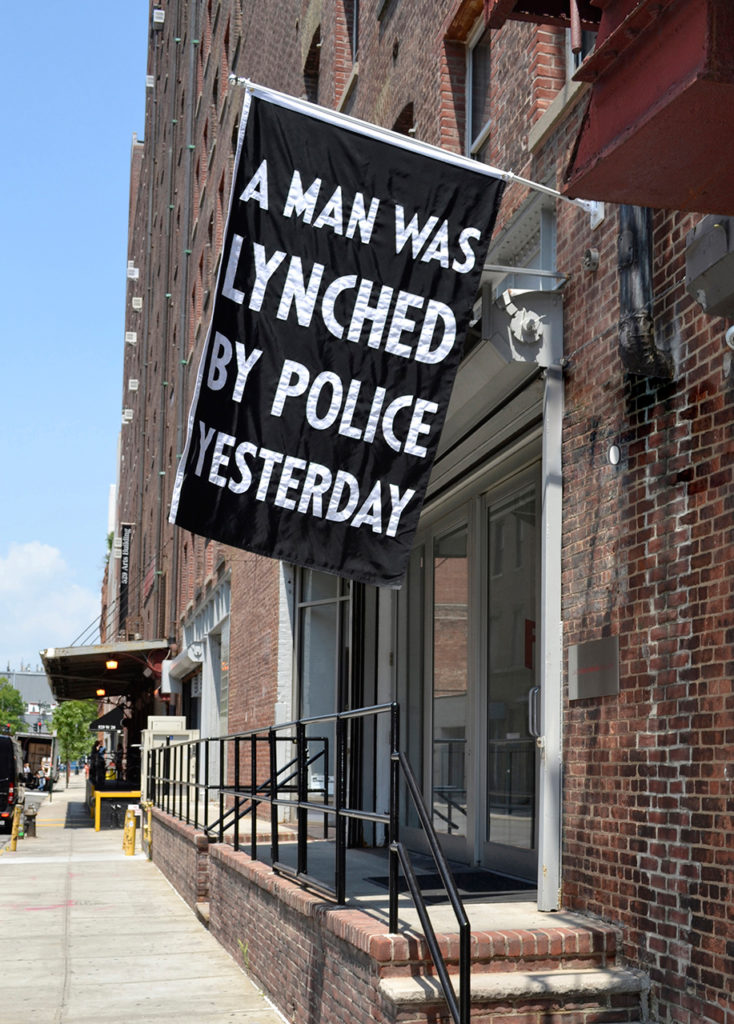

It certainly won’t be the only piece for which Scott is remembered. In 2015, Scott (born Scott Tyler, before adapting Dred Scott’s name) created a stark banner, A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday, in response to the killing of Walter Scott in South Carolina, and in the context of the deaths of Eric Garner in New York, Mike Brown in Ferguson, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, and Sandra Bland in Texas. The white text on the black background updated a banner that the NAACP used to hang from its national headquarters in New York City as part of their anti-lynching campaign, which read, “A man was lynched yesterday.” In July of 2016, in the wake of the killings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile in Minnesota, Scott flew the banner outside of the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York.

Scott’s work has often anticipated major social and political events. In 2008, the police wanted the Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora Arts shut down for showcasing Scott’s exhibition Welcome to America, which included an installation called The Blue Wall of Violence, showing standard FBI silhouette targets with a cast of an arm protruding from each, holding various objects that police had mistaken for guns when they shot unarmed people (the dates of the shootings in reference were also displayed above the target sheets).

This piece preceded the Black Lives Matter movement by five years. Controversy over Blue Wall made international news, which included this from the New York Daily News: “A cop-bashing art exhibit at a taxpayer-funded museum in Brooklyn portrays the city’s Finest as trigger-happy racists who have put bull’s-eyes on the backs of black New Yorkers.” Scott says that on a private message board for police, some officers claimed the museum should be blown up, and several made pointed threats to museum staff.

In 2010, as a harbinger of Occupy Wall Street, Scott stood in front of the New York Stock Exchange and burned $250 in small bills, one bill at a time. The piece was called Money to Burn, and was designed to explore the absurdity of a system in which the things people need to survive are turned into commodities, and in which the stock exchange can move billions of dollars around the planet and push people out of their houses, rendering them unable to even buy food, with just the push of a button.

“I did the one thing you shouldn’t do with money: burn it. Burning it is the one thing that everyone thinks is just crazy. But I was doing in extremely small form what happens on the stock exchange daily on a much grander scale.”

Although Scott made sure he was not obstructing pedestrian traffic on the sidewalk, police intervened after 25 minutes and ended the performance just 15 minutes later. Scott was issued a summons for disorderly conduct, which he then fought in court armed with a lawyer and with video evidence showing he did nothing illegal.

“The police showed up and knew there was something profoundly wrong with what I was doing but couldn’t find anything illegal about it,” he explains. “They tried to stop it, but ultimately became a part of the performance themselves.”

The ideas Scott presents are challenging to the system and threaten the status quo, he says. They make people uncomfortable. And they need to make people uncomfortable.

“Growing up in America during the Reagan years I felt a responsibility to rail against my own government,” says Scott. “In my work, there was a desire to focus on what are the big structural fundamental questions that would actually resolve this profound injustice and profound oppression. As a young Communist I kind of understood that this is not the end of history. A lot of times people will view whatever injustice they’re seeing as being permanent and that we have to work within it, but I don’t think so.”

His next project will continue tying together the threads of the history of injustice and oppression of Black people in America with the treatment of Black Americans in the present day. The Slave Rebellion Reenactment is an ambitious undertaking, a gathering of 500 people in period costume restaging and reinterpreting the largest rebellion of slaves in North American history, Louisiana’s German Coast Uprising of 1811, marching 26 miles over two days in the same location where the rebellion occurred.

Though still in the planning stages with a date yet to be finalized, Scott says that the planning and organization of the Reenactment will mirror that of the rebellion: clandestinely, by word of mouth, and in small cells.

“These one-on-one conversations with 21st-century people about why this 19th-century history is important is a major part of it; it’s the heart of the work,” Scott explains.

“These enslaved people had a plan to do the impossible; the extraordinary. People who were in the most suppressed version of society had the boldest vision of freedom. They were enslaved and wanted to end it. They planned for months, if not years. For them success was not killing white people; they actually wanted to seize the Orleans territory and end slavery, which was a very bold vision. What would it be like if that many people were concerned about police brutality? Our goal is to have zero killings by police again, and we will do whatever it takes to achieve that.”

(1) How do you like to collaborate?

Collaborations I most like are when the work that is created couldn’t happen without all partners contributing. A question that comes up a lot for me is “Why is this art?” and “Why aren’t we doing a painting?” Having conversations about why I’m even doing this or how to address it is somewhat unusual. Those are the collaborations I like to work on; where I can learn something and work with people whose experiences are different from mine.

(2) How do you a start a project?

Many of my projects now start with research: I think I know a little about something or there’s some issue I wish to address. On the basis of that I learn how to make an artwork. For A Man Was Lynched By the Police Yesterday I did research on the flag; for the Slave Rebellion Reenactment I have already been working for three years spending time in books and talking to experts, whether they are scholars or experts by experience.

(3) How do you talk about your value?

I consider value in putting out ideas and aesthetics that are transforming to society. My work is hopefully helping humanity get to an area where it [the status quo] is no longer that way, building a movement for revolution as art.

(4) How do you define success?

In the grandest way, there needs to be a revolution and my work needs to be contributing to that. That hasn’t happened yet in that there has been no seizure of power, but there is a movement building. I do think progressives and radicals need to think about success. A lot of times it’s dictated by funding sources, how many butts did you get in seats, or what legislation have you changed; that’s the wrong framework. I hope that my work is contributing to an environment where we will not be used for target practice anymore; where we are going to stop this by any means necessary.

(5) How do you fund your work?

I take money otherwise obtained through nefarious things and put it to good use. Money to Burn was a project funded wholly by the Franklin Furnace Fund for the Performing Arts for a relatively small cost. They are a re-grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, which is from tax dollars, so I’m taking money they could use to put more cops out there but instead they gave me money to burn.

Sometimes individual contributors people buy work of mine; that goes into paying rent and buying art supplies. For the Slave Rebellion Reenactment, $100,000 has been raised so far by foundations and grants, then some will come from individuals [through a Kickstarter campaign]. Some supporters will be wealthy and want to contribute to something good, and I self-fund some of my work too. In the past I had more day jobs than I do now.